How Oct. 7 changed Jewish life at Yale

Yale’s Jewish students recount a year of grief, confusion and resilience.

Yale Daily News

Hannah Saraf ’27 was spending Family Weekend on campus with her parents on Oct. 7, 2023, when she learned about a massive attack in southern Israel that day. Saraf, whose father is Israeli, anxiously contacted a childhood friend whom she knew was in Israel. Her panic increased when she learned that her childhood friend had gone to visit her family in the South for a holiday that weekend.

“She said ‘I am here right now and there are people outside of our house.’ She didn’t even live there. She just went to go visit her family,” Saraf said. “That was really scary, when I didn’t hear from her. I was really, really anxious about the people I knew, but after that cleared I was just sad and honestly, I was immediately really worried about the toll this was going to take on Palestinians.”

When Hamas terrorists entered Israel in the early hours of Saturday, Oct. 7 — around 11:30 p.m. EST on Oct. 6 — Jewish students were celebrating the holiday of Sukkot, many at Yale’s Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life with relatives visiting for Yale’s annual Family Weekend. Some learned of the unfolding terror attacks from social media or Israeli news outlets on Friday night. Others, who did not use technology on the holiday due to their religious observance, heard only fragments of information throughout Saturday and Sunday, the Jewish holiday of Simchat Torah.

In the ensuing days and weeks, news outlets reported the deaths of over 1,200 Israelis in the attacks, including 364 individuals killed while attending the Nova open-air music festival near Kibbutz Re’im in southern Israel. Video footage and subsequent reporting confirmed reports of sexual violence and mutilation. Over 240 individuals were taken captive by Hamas. 97 hostages are still being held in Gaza — at least 34 of whom Israel has concluded are no longer alive.

At Yale, the Oct. 7 attacks set in motion a year of large campus protests responding to Israel’s retaliatory war in Gaza, which has killed at least 41,500 Palestinians. Over 2,000 individuals have been killed in Lebanon since Oct. 7 as well, in Israeli fire exchanges with Hezbollah, a U.S.-designated terrorist group.

The News spoke to 16 Jewish students from across Yale College and three graduate programs who described how Oct. 7 and its aftermath changed their lives, the Jewish community and Yale.

“Walking in a nightmare”

Sabrina Zbar ’26, a member of Yale’s small Orthodox community, studied for a year in Israel and has many close family and friends who live there. She remembers “every detail” of how she spent Oct. 9, 2023, her first day back on campus after spending the holiday weekend in South Carolina with friends. Zbar described that Monday as “one of the worst days” she has ever experienced.

“Being on campus that first week back just felt like I was walking in a nightmare that I couldn’t really wake up from,” Zbar said. “I just felt so helpless on campus and so sad and alone in my sadness.”

Like most observant Jews, Zbar learned about Hamas’s attacks “in stages,” as she did not turn on her phone to check the news until after Simchat Torah ended on Sunday night.

On campus, similar scenes of confusion and grief played out over the weekend. Nava Feder ’27, who is observant, described knowing throughout the weekend that an attack had happened, but not being aware of the scale. Yossi Moff ’27 recalled that Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, then the University’s Jewish Chaplain, made an announcement in the middle of the morning services about an attack on Israel, killing hundreds. When services ended and students arrived at Slifka for Shabbat lunch, information began spreading.

Sophie Schonberger ’26 learned about the attack before she went to sleep on Oct. 6. The next day, she was reluctant to go to Slifka, where she had intended to take her visiting family, because she did not want to “ruin” the festivities for students who had not checked their phones.

“I have these vivid memories of sitting at breakfast feeling frozen because I was just trying not to break down,” Schonberger said, recounting the morning of Oct. 7. “I’d seen that there was a big attack, and I knew that a lot of people had been killed and kidnapped.”

Schonberger had a close friend attending the Nova music festival. She later learned that her friend survived; hundreds of other attendees did not.

For Simchat Torah, the annual Jewish festivity to celebrate finishing reading through the entire Hebrew bible, the Slifka Center had organized a “Torah Run” — dancing and singing around campus with the Torah. But as news trickled in of the ongoing attacks, Slifka’s student board decided to cancel the event, instead hosting a singing circle and a “space for discussion,” according to an email sent on Oct. 7 to Slifka’s mailing list.

Moff described the singing circle as emotionally difficult, especially because some of the participants already knew the magnitude of the unfolding attacks, while others did not. The next day, Sunday, took “forever to go by,” he said. Finally, after Simchat Torah ended on Sunday night, Feder, Moff and other observant students powered on their phones to check the news and reach out to family and friends.

“All of this is in perspective,” Moff said. “I had privilege in watching it from thousands of miles away. I wasn’t in Israel with constant sirens.”

Like Schonberger and Moff, several of the students interviewed have close friends and relatives who live in Israel. Even for those who did not, news of the attack brought grief and horror.

Sammy Rosenberg ’26 described the attack as a tragedy that “transcended any personal connection” to those who were killed, kidnapped or injured. He recounted explaining to friends the devastation that the attack brought on his community, which he attributed to “a very strong sense of peoplehood” in the Jewish faith.

School resumed on Monday, Oct. 9. While Zbar attended classes, she was unable to focus. She described feeling helpless, and crying when professors mentioned the attack or expressed sympathy with those impacted, even though she appreciated their acknowledgment. She also remembers feeling a sense of foreboding.

“I had a sense that people aren’t going to speak out against Israel today, because citizens of Israel were just massacred, but in a few weeks when Israel retaliates, no one’s gonna be quiet about it,” Zbar said.

Feder and Saraf also recalled feeling immediately worried about Israel’s retaliation to the attacks, and the toll that it could take on Palestinians, including innocent civilians.

Jewish community — “resilient in its pluralism”

The majority of Jewish students who spoke to the News said they turned to the Yale Jewish community for support in the days following Oct. 7 and felt it unify under the tragic circumstances.

“Whenever I wasn’t in class, or sleeping, I was basically in Slifka,” Moff said. “It was a place where I could be with people who cared about what was happening, understood what was happening, were thinking about what was happening.”

Zbar added that Slifka then could often feel overwhelming.

“The Jewish community did come together, but I didn’t even feel like Slifka was a place I wanted to be, because it felt like walking into a funeral home,” Zbar said.

But, students explained, as much as the Jewish community united over the tragedy of the terrorist attacks, internal divisions and disagreements grew as the war in Gaza escalated.

Saraf described this change by comparing Slifka gatherings to a “high school cafeteria.” She explained that although the community comes together for services and events, students often end up congregating in politically like-minded groups “without much movement across.”

Rosenberg described Slifka as having a dual purpose, which at times can cause conflict. On the one hand, Slifka is an organization meant to support Jewish students — regardless of their political views regarding Israel. On the other hand, Slifka is affiliated with Hillel International, an organization that has chapters at campuses across the world and is explicitly pro-Israel.

“It’s complicated to try to be a Zionist organization, and also support your students who don’t hold that position,” Rosenberg said.

Elijah Bacal ’27, a student involved with both Yale Jews for Ceasefire and the Slifka Center, said that although he has felt accepted at Slifka, some left-leaning Jewish students have felt ostracized in mainstream Jewish spaces on campus.

“In my experience, Slifka has been very resilient in its pluralism, in its acceptance of everyone,” said Bacal. “But there are definitely Jews on the left who feel like they can’t be fully respected in the Jewish community at Yale.”

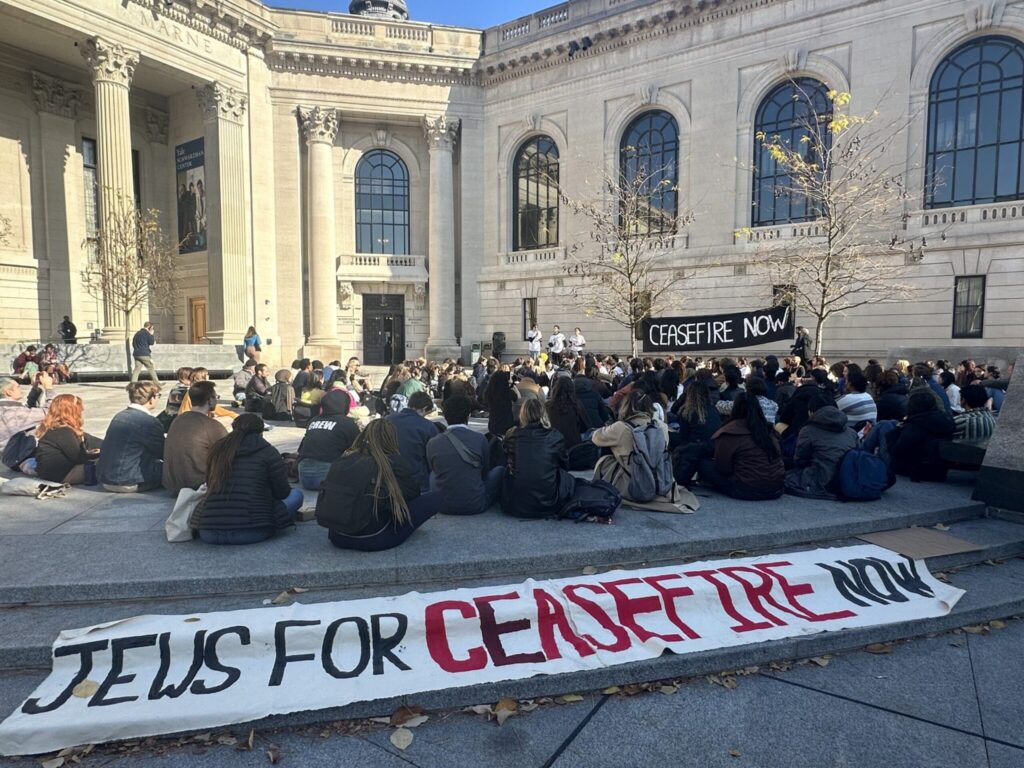

Jews for Ceasefire is run by Jewish students active in the larger pro-Palestinian movement on campus. Unlike Yale Friends of Israel or Yale’s chapter of J Street U, Jews for Ceasefire is not an official affiliate of the Slifka Center.

In the aftermath of Oct. 7, Feder — who has Israeli relatives and describes herself as “pretty left-wing on Israel” — found herself looking for a space with like-minded peers. After speaking with other left-wing Jewish students, she helped found Jews for Ceasefire in November.

The following week of Oct. 9, Yale’s campus saw a series of rallies, vigils and a petition to oust a pro-Palestine professor.

On Oct. 13, Israel began its ground invasion into the Gaza Strip.

“Unsettled, but not unsafe”

Students at Yale began mobilizing in support of Palestinians just a few days after the Oct. 7 attacks and Israel’s immediate retaliation. In the first two months, 15,000 Gazans were killed. Throughout October and November, student groups held rallies and events demanding a ceasefire in Gaza.

In April, protests intensified. Students, drawing on the war in Gaza, rallied for the University to divest from weapons manufacturers and set up two encampments on Beinecke Plaza and Cross Campus, respectively. While clearing the first encampment, the Yale Police Department arrested 48 student protesters for trespassing.

Mika Bardin ’26, who describes herself as a left-leaning Israeli, felt that the campus political climate last spring became increasingly unrelated to the war and removed from the nuances of the issues.

“It came to the point where it was, are you going to wear a keffiyeh to class, or are you going to wear a yellow ribbon?” Bardin said, referencing symbols of solidarity with Palestinians and Israeli hostages, respectively. “It’s this thing that is so unrelated to the war, just so oversimplified.”

Six students told the News that the divestment encampments did at times make them feel unwelcome, but not physically threatened.

“I am grateful that I never felt physically unsafe,” Zbar said, “but being unsettled for nine months definitely takes a toll.”

Zbar and other students cited protests at Columbia University as comparatively more threatening for Jews on campus than those held at Yale. At Yale, Moff said, protests “didn’t get to the point where [he] felt unsafe walking around them,” but he still didn’t “feel welcome or at home.”

None of the students interviewed by the News felt that they had experienced explicit antisemitism at the pro-Palestinian protests. Some students, however, pointed to specific protest chants, like those that called for “intifada” — the Arabic word for “uprising” associated with periods of popular violent resistance against Israel — as particularly alarming.

Moff and Esther Levy DIV ’24 both separately recounted a disturbing experience at the second encampment, which stood on Cross Campus from April 28 to 30 when it was cleared by the Yale and New Haven police departments.

Levy recalled that she and a group of Jewish students — some of whom were wearing kippot — were trying to pass through the encampment. They were asked to agree to a set of community guidelines, including “being committed to Palestinian liberation and fighting for freedom for all oppressed people,” that the protest marshals had declared a condition for walking through Cross Campus. Then, Levy recounted, the marshal speaking with the group asked them to remove their shoes — a condition that Levy and Moff did not think was asked of any other individual.

“It felt like there was something that was charged about the fact that we were very visibly Jewish,” Levy said. “We didn’t take our shoes off. That was ridiculous.”

Moff said that he felt the request was “like a power trip.”

Two encampment organizers, who requested anonymity due to doxxing concerns, denied that this incident had happened, and told the News that antisemitism was not tolerated in the encampment.

For Levy, her encounter with the marshal shaped her perception of the protest. She said that she believed — and “to a certain extent” still believes — that student encampments were protests for peace, not antithetical to her own beliefs.

“Meeting people at the encampment, trying to engage in a conversation, made it very clear to me that maybe at the core of the protest, we do share beliefs that are very similar and very aligned. But the ways that things were going down were wildly different,” Levy said.

Feder, who participated in some campus protests through Jews for Ceasefire, told the News that members of Jews for Ceasefire had “a lot of conversations” about engaging with the larger protest movement at Yale.

Bacal explained that he and other Jewish protesters raised concerns about the language used at protests — specifically, “intifada revolution” and “from the river to the sea” — and that encampment leaders were “very receptive” to their concerns.

But, Bacal said, “policing language” at the encampments had a limit, considering how high the stakes were for so many protesters.

“Just as the Jewish community has people serving in the IDF, families in Israel and relatives who died on Oct. 7, there are people with families in Gaza right now. There are people with families in the West Bank right now, families in Lebanon right now,” he said. “We’re gonna tell this person whose family is trying to flee for their life from this bombing exactly what language they can and cannot use? That’s a really fucked up thing to do.”

As the encampments across the country ramped up last spring, the protests at Yale often made headlines in national papers.

Some students interviewed by the News said that these articles about antisemitism at Yale were dangerously misleading — giving their relatives at home a false perception of what life is like for Jews on campus.

“Even now, during Rosh Hashanah, I was at a temple with my family in New York. There, they were all talking about getting donations to prepare lawsuits [and have committees] to help make sure Jewish students feel safe,” said Saraf. “I was there thinking, I’m very openly Jewish. I’ve never been discreet about that, and I never felt physically unsafe.”

Losing “ideological safety”

Multiple students interviewed by the News described a shift in campus rhetoric, in which Zionism became a popular topic of discussion and one that many felt was misunderstood.

Maurice Samuels, a professor in Yale’s French department and the head of the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism, explained that for many Jews, Zionism means merely the right of the Jewish people to a country as a form of national self-determination.

After Oct. 7, however, conceptions of Zionism in the broader public have shifted. Now, Samuels said, the word is associated with “the most extreme forms of Israeli aggression,” or even an idea of Jewish supremacy in Israel.

“I don’t think for many Jews, that is what it means at all,” Samuels said. “For many Jews, it’s possible to consider yourself a Zionist because you support the right of Israel to exist, and be completely opposed to [Israeli Prime Minister] Netanyahu or even this war.”

The morning that Yale’s first encampment was cleared, protesters chanted “Free our prisoners, free them all, Zionism must fall.” Later that day, at a protest “seder” — a Passover traditional meal — hosted by Jews for Ceasefire, several attendees named Zionism as something “plaguing” Yale.

Schonberger, who identifies as a Zionist, emphasized that support of Israel is, for her, a personal choice instead of an ideological one.

“Being Jewish and being a Zionist, for me, was never supposed to be political,” Schonberger said. “Obviously, yes, there is political Zionism, but to me, it was always about ‘this is who I am.’”

For Rosenberg, the dramatic shift in public perception of Zionism was frightening. He described feeling like Zionism became a “dirty word.” Though he did not fear for his physical safety, he described a loss of “ideological safety.”

Rosenberg recalled feeling concerned that an echo chamber had been created throughout campus, in which being a Zionist was unequivocally “immoral.”

“I’m a Zionist because I believe in the importance and necessity of homeland for the Jewish people, a sovereign state in the land of Israel,” Rosenberg said. “Nothing inherent to my Zionism necessitates or at all indicates that one supports genocide, and that was a terrifying thing I felt being lobbied against me.”

Most Jews in the United States identify with Zionism and believe American support for Israel is critical. But the question of whether Zionism is an inherent part of the Jewish identity is difficult to answer, Samuels said.

Connection to the land of Israel is embedded in the Jewish faith — prayers said during the holiday of Passover end with a hope that next year, the holiday will be celebrated in Jerusalem. Some religious Jews opposed the creation of Israel as they believed the return to Israel should only happen in a messianic age, but most prominent Jewish organizations in the United States now consider support for Israel as a central concern for the American Jewish community.

“A lot of American Jews grew up with a strong identification with Israel as a country and a pride in what Israel has achieved,” Samuels said. “I think that it’s very painful for a lot of Jews to confront the instances where Israel doesn’t live up to what they consider Jewish values.”

That pain has led many Jews to “separate themselves from Israel,” Samuels said, and similarly, separate the State of Israel from Jewish identity.

Samuels believes that the past year has been especially difficult for Jews who consider themselves “in the middle.”

“For Jews who feel invested in a Jewish state, but also want a Jewish state alongside a Palestinian state, that hope has been really receding, and I think that’s very painful,” Samuels said.

“Calmer on both sides”

Some students interviewed by the News said that Oct. 7 and its aftermath has changed their relationships at Yale, but believe that this semester the campus political climate will continue to settle down.

“My Yale definitely did shrink a lot,” Schonberger said.

Bardin said that she has difficulty finding space on campus to speak about her dissatisfaction with the Israeli government, as a citizen of the country. Because of her nationality, she said, people “wanted to put [her] into a box,” only caring about “which one of the two sides [she] fell on for one of the most nuanced conflicts.”

All of the students interviewed expressed that the environment has been more relaxed since the 2024-25 academic year began.

“It’s been a lot calmer on both sides,” Rosenberg said, speculating that students involved in activism relating to the war might be experiencing fatigue.

On Sept. 24, four faculty members — including Samuels — gathered to discuss antisemitism, anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia on a panel moderated by University Chaplain Maytal Saltiel. The event, though open to any community member wishing to attend, was advertised as being neither recorded nor filmed.

At the panel, the faculty members discussed their personal encounters with prejudice on campus in the past year. They also talked about the support they felt from their colleagues and the Yale community at difficult moments.

Saltiel told the News that the panel was intended to be “the first in a series” of events organized jointly by a faculty advisory committee for Jewish student life and a faculty advisory committee for Muslim and Arab student life — both of which she chairs.

Samuels believes that the panel was organized in part due to a sentiment that the University did not do enough to address its topic last year.

“I definitely heard several times, ‘Oh, this situation is just too hot right now, it’s too tense, people aren’t ready for that kind of dialogue,’” he said. “I’m not sure if that’s really true. Maybe we should have done it anyway. Maybe that’s precisely when it was most needed.”

The Slifka Center will hold a vigil on the anniversary today at 7 p.m.