Maria Arozamena

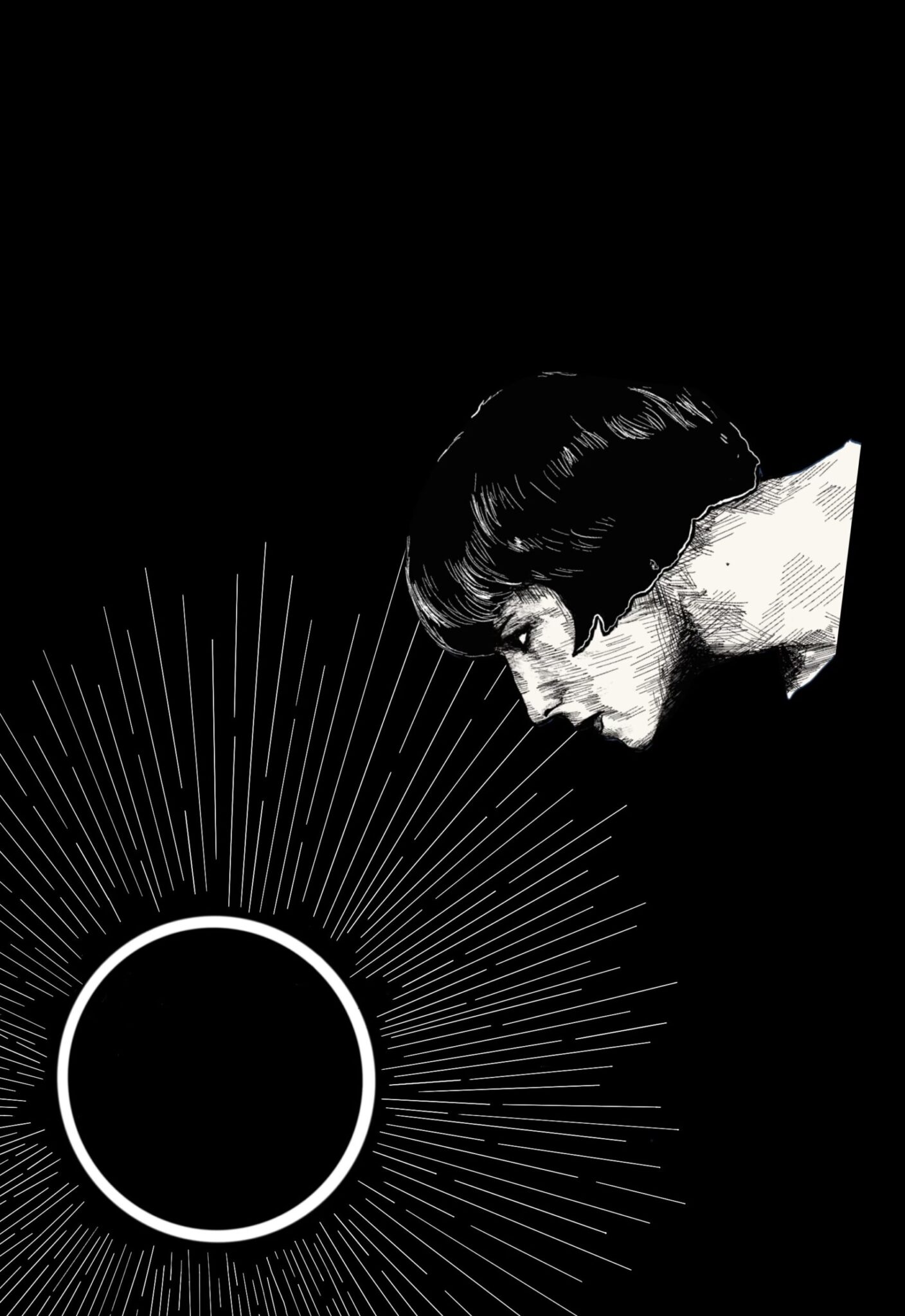

I am obsessed with ghost stories — trickles of the unknown, in whispers, against the skin of your ear as you walk through Cross Campus at 2 a.m.; watching books fall out of shelves in the library without being touched; shadows that shift through the winding tunnels in the basement, as you waddle in deep, uncanny solitude. Werewolves and witches, wickedness, hauntings.

I become lost in these moments of fear. It is only when I feel my heart sink and a weight pressing down on my throat that I suddenly begin to understand how centuries of humankind have led their lives with myths. Believing in apparitions, stories of the supernatural, rituals and duties and deities suddenly becomes second-nature to me, and in these moments, I begin to pray. I feel most religious when I am scared; I begin to feel the gravity of my existence stranded alongside the immensity of the human experience, and the totality of the natural world.

So, it’s no wonder that I felt that totality — or at least 92 percent of it — on Monday, gazing at the white-gold blaze of stellar wedding bands in the sky. Witnessing the eclipse from Leitner Observatory, I was half marveling at the sky and half mesmerized by the masses of people standing heads-crooked mouths-gaped all around me.

A part of me expected the world to fall apart in a burst of flames and glory, catapulting us into the new-world dystopian era that I’ve been anticipating since 5th grade. If YA novels taught me anything, it’s that you have to be on your toes if you experience a) a seismic shift b) a solar eclipse c) a randomly included romance subplot all in the span of one weekend.

Alas, all that occurred in the 20 minutes of feverishness following the eclipse were exclamations of “wow, that was so cool!” and “dude, wasn’t that crazy?” battling against bitter “it wasn’t that cool”s and “that was it?!”s. The shadows of near-totality didn’t take long to escape us, and onto PSETs and Italian homework we progressed.

Earlier that day, I panic-texted half of my contacts asking where I could find eclipse glasses. I wasn’t about to miss the event at the tips of everyone’s tongues, and I knew that if I didn’t have immediate access to protective eyewear, I wouldn’t be able to stop myself from staring straight up at the sun.

Even with eclipse glasses, once I acquired them, there’s something about witnessing the event with naked vision — retinas on full blast — that tempts me against caution, makes me a little too un-wary and grants me a sense of confidence that I really should never be allowed to have. It’s the same boldness that dares me to roller skate down Science Hill at midnight and to drive to Philadelphia on a Thursday evening despite a 9 a.m. the next day. Both of which, by the way, are never good ideas.

It’s part-greediness, a want to see the world and leave no part unseen, no experience unnoticed. A desire to collect the spectacular, like tokens of experience that I can put on a mental trophy-case and polish for years, sprinkle them into my daily conversations like flakes of paprika — “Hey, remember that eclipse 30 years ago when we were back in New Haven?” “Didn’t see it,” “Oh, what a shame! It was one of the most memorable moments of my life.”

Maybe it’s part-petty attitude, a desire to compensate for the worlds I feel I haven’t seen and the lands whose grounds my feet have yet to graze. I think seeing things like eclipses, witnessing the small shakes of the earth, make me feel more grounded and on the same level as others around me. What I can’t relate to in visiting London or walking through the Great Wall or spending spring break on a yacht in Cancun is reclaimed in sitting down on a picnic blanket, munching on a pack of Fritos and watching the moon’s lapse onto the sun. It’s a sort of anti-FOMO, a bragging right that, selfishly, a part of me wants to claim.

Maybe it’s also my desire to make a ghost-tale out of nature, of my want to be moved so badly that suddenly I’m jumping up and down, giddy, at two space rocks that intersect for just a moment in time. It could be the end of the world, it could be the beginning of a new saga — Twilight, anyone? — it could be anything and everything, nothing at all or a completely new life.

When I was watching the eclipse, I was one of many mesmerized faces staring at the sky, some with wonder, some with partial fear, mine with infected joy. As much as I left Leitner feeling aware of how quickly a moment passes — boom, 25 minutes and the masses were already migrating — I also felt comforted, not only by the ecstasy of discovering the natural phenomenon for myself, but by the waves of shared experience I felt with everyone around me.

There were no werewolves, unfortunately; no prickles on my skin or whispers from ghosts, no calling from the beyond to satiate my desire to be spooked. But I did feel that sort of religion, that succumbing to forces greater than myself, as I watched all the faces around me move in unison towards the sky and to the beyond.

No matter how behind I was on my architecture project; no wonder the itchiness of the sweater I wore or the bitterness of the cold that slapped me; no matter the gray clouds that blotted the sky like guardians of a gate to the unknown; all of this stopped to let the moon overtake the sun, to let the natural mysticism of our solar system, our galaxies, take the reign.

Nothing else mattered for a moment, because I got to watch the eclipse.