For this piece, in honor of Women’s History Month, I had the opportunity to interview Monique Truong ’90, a Vietnamese-American author known for her works “Bitter in the Mouth,” “Book of Salt” and “The Sweetest Fruits.”

When I first read Truong’s “Bitter in the Mouth,” it quickly became a favorite of mine. My memories of reading the book are ones of home. I read much of the book lying in a hammock in the shade of a magnolia tree fearing the blistering North Carolina weather.

I think my fondness for “Bitter in the Mouth” is due to its familiarity. The book follows Linda Hammerick as she navigates friendship, family and adolescence in Boiling Springs, North Carolina — a small, southern town not too different from my own. Truong exquisitely captures this place, the people that inhabit it and, most acutely, the emotion of this stage of life.

Similarly, her most recent novel — published in 2019 — “The Sweetest Fruits,” is also told from the first-person perspective of a woman; in fact, several women.

When I asked how she would define being a woman, or womanhood more broadly, Truong said:

“It’s to be defined by your body, whether you like it or not. I think to unpack that, it means you are not a blank slate in the world. There is already a narrative, multiple narratives, written about your body that you are essentially born into. Some of it may be things that you can embrace and you feel connected to, and others…are things that you will need to push against.”

In this moment, in the wake of Roe v. Wade and ensuing uncertainty over the governance of female autonomy, it is so pertinent to address how women are often defined by their bodies.

Truong continued, “I think the struggle for me, and for many women, is that journey of defining what it means to be a woman in relationship to these existing narratives. What does it mean to you and not what others have imposed upon you?”

Reconciling mixed emotions over what it means to be a woman is its own battle. Truong voiced her experiences and the unique difficulties that came with growing up in the South as an Asian American woman.

“I have never been comfortable within my body. Part of it was actually growing up in the U.S. … it was something that was problematic to other people. And it was something that I could not understand as a child because, not only was I in a female body — which later would become even more significant to all that is going to try to define me — but I was in an Asian body. When I came to the U.S. and specifically Boiling Springs I became something that I didn’t understand, which was this racial other, this Asian other.”

When feeling uncomfortable in her body, Truong says that she has always found a certain redeeming confidence in her brain, her intellect.

“The thing about my body that I am comfortable with, and have always been comfortable with, is my brain. That has never let me down!” Truong says laughing.

Truong then added, “[My brain] has gotten me everywhere that I needed to be in my life today.”

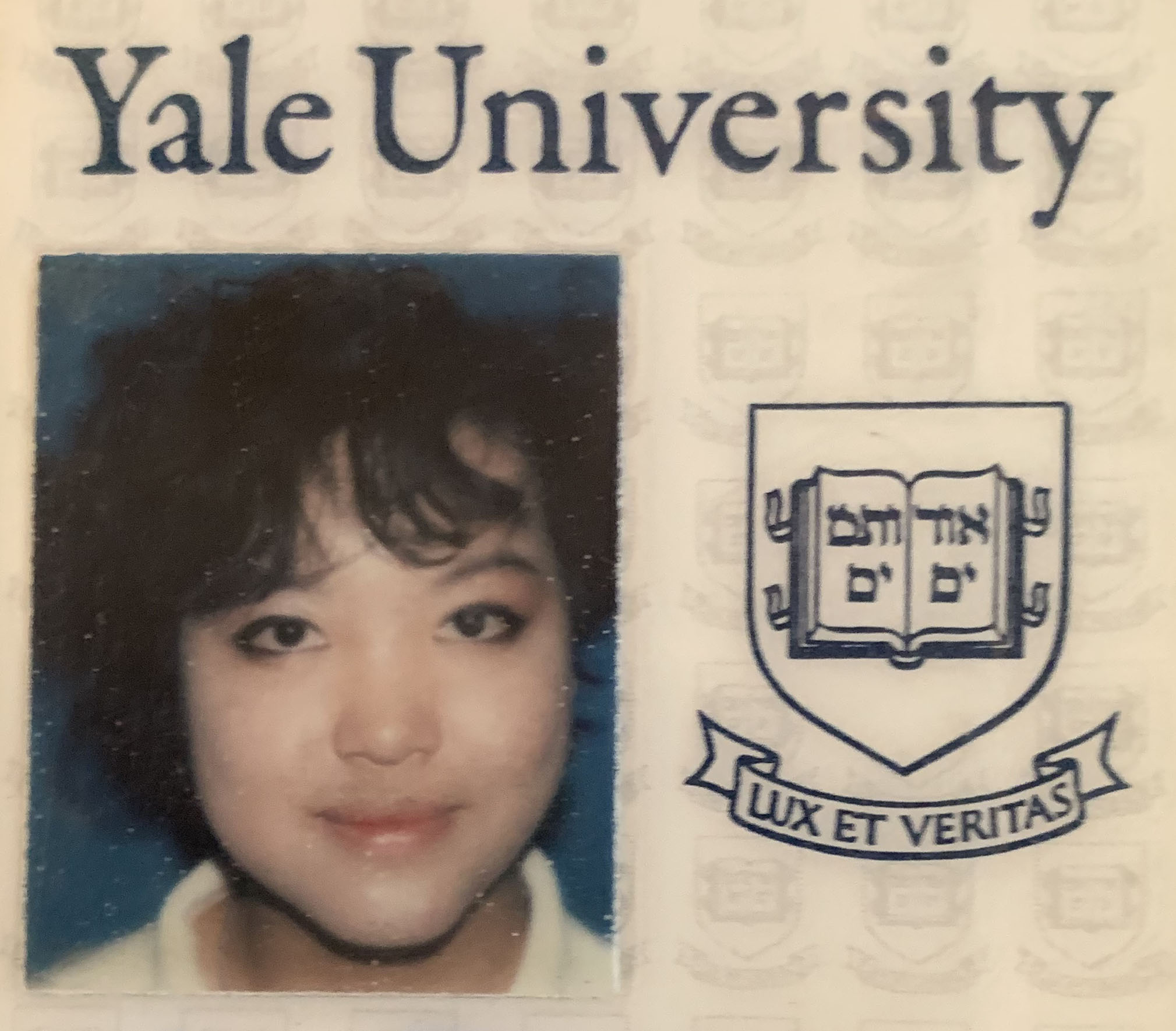

The everywhere Truong refers to includes Yale College, where she studied literature.

Truong arrived at Yale, typewriter in tow, in 1986 — 17 years after Yale College first began admitting female students.

When asked if her educational career’s proximity to Yale College’s first female admits affected her experience Truong began, “I don’t think I understood the impact of the relatively brief history of women at Yale and … what sort of message it sent to me as I was a student there.”

During Truong’s time at Yale, the odes to female success that we see around campus now — The Women’s Table, residential colleges Grace Hopper and Pauli Murray and the Portrait of Yale’s first seven women doctorates in Sterling, to name a few — weren’t around.

Commenting on this lack of representation, Truong said, “There hasn’t been that long history of women playing a significant role at the university. And, you know, that might seem like a kind of superficial or trivial thing like ‘What does it matter if the paintings are of white men?’ Of course it matters! It matters because every single day this is what you’re looking at.”

Female role models are the igniters of progress, as they do what has never been done. Seeing women on screen, or reading about them in books, is what allows young girls to envision their futures unobstructed by what a woman can or should be.

Truong spoke a lot about how she has been shaped by both real and fictional women, primarily her mother and Jo March from Louisa May Alcott’s “Little Women.” “[Before Jo], I don’t think I had read about a woman, a girl, being a writer or wanting to be a writer,” Truong said. “Reading about her desire and seeing her so doggedly working towards it and wanting this life of letters that was just kind of the beginning of the road map.”

When asked about who inspires her the most, Truong responded, “…my mother because she has gone through the kind of life changes that I could never imagine: being a woman in her thirties all of a sudden losing her country, her language, her family, everything and coming to the U.S. and having the ability to continue to live and create a life.”

Truong’s mother later went to nursing school in North Carolina to become an Intensive Care Unit — ICU — nurse. Reflecting on this time in her mother’s life, Truong remarked that she didn’t think she would have that kind of strength.

When asked what she would say if she could go back in time and give a piece of advice to the girl who left Saigon, Vietnam for Boiling Springs, North Carolina, Truong provided a sentiment that many, regardless of gender, age or sexual orientation, will resonate with:

“There are certain limits to words. Even though I’m a writer. If I reach back and tell that little girl ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’ I don’t think she can actually do very much with that. I think what I would want to do for her is to hug her. You know, there are other forms of communication.”

As March comes to a close, take a moment to reflect on how far we’ve come; as individuals, as a university, and humanity as a whole.