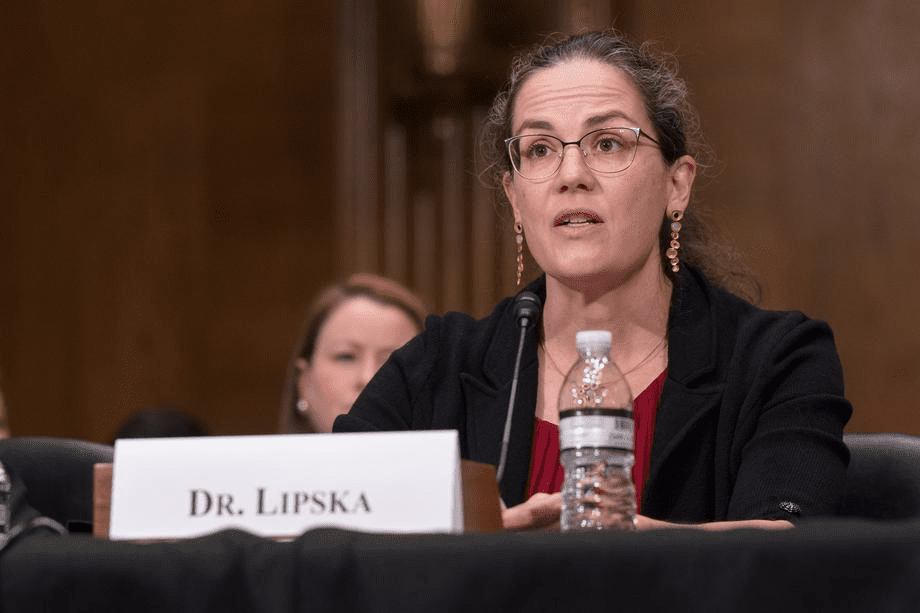

Yale doctor on the Senate stage: Kasia Lipska’s fight for accessible diabetes solutions

Dr. Kasia Lipska unveils the financial strains patients face in her fight for accessible diabetes and obesity treatments, urging a prescription for change.

Courtesy of U.S. Senate Photography Studio

When Kasia Lipska consults with diabetic patients, she frequently has to prioritize the affordability of diabetes medications over their effectiveness.

Lipska is a professor of medicine at the School of Medicine who specializes in endocrinology and diabetes. On Dec. 14, she testified at the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing titled “What is Fueling the Diabetes Epidemic?” During the hearing, she underscored the need for the federal government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies to lower drug prices to address the root causes of diabetes and obesity.

Many of Lipska’s patients suffering from Type I Diabetes — a chronic condition where the pancreas produces little-to-no insulin, the hormone responsible for regulating blood sugar levels — spend nearly half of their household income on insulin, which is vital for them to stay alive. Many also struggle to afford medications such as Ozempic — the brand name for semaglutide, which the FDA approved to treat Type II Diabetes — or Wegovy, another brand name for a similar drug approved for weight management.

“I see patients in clinic who struggle paying for the medicines and often don’t take their medicines because they cost too much — and I see the consequences,” Lipska said in an interview with the News. “I get very upset about this, and I get very angry at our healthcare system because people suffer when they cannot afford the medications they need.”

On the stand, Lipska presented evidence from a 2017 survey conducted at the Yale Diabetes Center which showed that one in four diabetes patients who were prescribed insulin had to ration the medication due to cost. According to Lipska, though recent advocacy efforts have led to a decrease in insulin prices, the medication remains expensive.

These novel medications are not cheap. Patients with Type II Diabetes — a condition in which insulin is unable to lower a patient’s blood sugar — often pay over $900 per month for Ozempic. Similarly, patients suffering from obesity have to pay $1,300 a month for Wegovy. Patients must take these medications continuously for an indefinite period in order to maintain their ongoing effects.

“Patients are looking at a potentially lifelong treatment and could be facing the most expensive subscription service in the history of medicine,” Lipska told the News.

In the hearing, Lipska noted that if Medicare were to cover Wegovy for its beneficiaries with obesity, American taxpayers would have to pay $268 billion.

Further, according to a study conducted by Luan Yu, a cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine at the School of Medicine, the populations least able to afford these treatments are the ones who need them the most.

“We found that these minority populations who have higher prevalence of obesity also have more financial barriers, in terms of accessing healthcare and afford[ing] the medications,” Lu told the News.

However, other countries are avoiding these steep costs. Lipska testified that Ozempic costs $100 per month in Sweden and just $80 in Australia and France.

In contrast, patients in the U.S. must pay 10 times that amount. For Lipska, the lessons learned from insulin affordability should inform how the government negotiates prices with pharmaceutical companies for novel medications like Ozempic.

“The Inflation Reduction Act already authorizes the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate prices with pharmaceutical companies under specific provisions, and for a limited set of drugs,” Lipska told the Senate.

According to Lipska, this process involves aligning the launch price with the drug’s value and what patients can afford. She argued the government should sit at the negotiating table with pharmaceutical companies such as Novo Nordisk, the developer of Ozempic which has a market value higher than Denmark’s GDP.

Still, Lipska emphasized the need to tackle diabetes and obesity upstream, instead of relying on drugs. For her, more long-term preventative solutions, such as reducing food deserts, are more favorable than using weight-loss medications.

“In cardiovascular disease prevention, we always talk about prevention being more cost-effective than management or treatment,” Lu told the News. “It’s better to prevent people from becoming obese. Then, if they become obese, you treat them.”

In the hearing, Senator Bernie Sanders — chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee — underscored Lipska’s call to action.

“Nearly 30 years ago as I think we all know and the American people know, Congress had the extraordinary courage to take on the tobacco industry whose products killed nearly 400,000 Americans every year including my father,” he said. “Now is the time for us to seriously combat the Type II Diabetes and obesity epidemics in America.”

Over one in 10 people in the United States suffer from diabetes.