Whose land are you on?

If you’re reading this on campus, you’re on the rightful lands of Algonquian-speaking peoples who have existed here since time immemorial and continue to exist. If you’re not on campus, you’re likely still living on dispossessed Indigenous land. Today’s Indigenous students at Yale work to carry on the legacy of their ancestors, fight for their communities and preserve their stories.

Yale’s Native community has faced numerous challenges and discrimination on the journey to accomplishing these goals. We are ready to tell you our story.

Walk through the past year in the life of a Native student at Yale and learn about our needs for the future.

Feb. 14, 2022

The Native and Indigenous Student Association at Yale — the oldest and largest Native student organization on campus — begins its spring programming with an annual Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s Vigil on Feb. 14. We organize speeches, moments of silence, song and visual displays designed to bring campus awareness while simultaneously supporting our community members carrying emotional burden due to this crisis. This vigil is a heavy event. Our community members shoulder this weight knowing that this vigil has the potential to create positive change. In pursuit of this change, our community brought back the MMIW Vigil post-lockdowns with renewed resolve. The newly-elected board worked tirelessly to assemble the programming, arrange the event and bring physical awareness to campus spaces.

Following years of similar physical displays, the decision was made to bring red — the common color for MMIW awareness — to Cross Campus. Red posters, red ribbons and red hand prints punctuated the gothic stone walls around the Women’s Table on Cross Campus in advance of the vigil. These displays were designed to evoke response and reflection while minimizing labor placed on facilities staff; the posters are inherently non-damaging, ribbons were removed easily by student organizers and the red-painted handprints were created with water soluble, washable, Crayola-brand paint.

Our community planned for and communicated our intention to manage the putting up and taking down of these displays internally. Facilities was contacted in advance, and verbal support was received. The Yale community woke on the morning of Feb. 14 to a Cross Campus transformed; the displays were widely received by the student body and sparked conversations around MMIW. However, the success of these displays became quickly overshadowed by threats and anti-Indigenous rhetoric.

The Indigenous community on Yale’s campus is used to facing pushback, and this vigil was no exception. Our co-presidents received emails, text messages and calls from a student life administrator, and they were told in no uncertain terms that the displays must be taken down immediately following the vigil’s conclusion. Heeding this warning, dozens of community members and non-Native allies worked together to scrub the painted handprints from the walls. Had it not been for the below freezing temperatures, the clean-up would have been easy and no further issue would have arisen. Students were forced to leave the area to avoid frostbite with approximately 95 percent of the display removed, as at this point the washed wall was now frozen over with ice.

Students returned the next morning to resume clean-up, but it was too late; facilities had begun cleaning with power washers. Though the walls were easily cleaned within an hour using these machines and no lasting damages occurred, student leaders received additional concerning communications. Some administrators demanded a list of names of involved students which inspired fear of punitive action. The co-presidents — along with the rest of the NISAY board — faced days of intense worry and anxiety, unsure what would happen to individuals or the organization as a whole as a consequence of this apparent condemnation of peaceful protest.

April 30, 2022

The fallout from the MMIW Vigil left severe and lasting trauma on our community. However, this would not be the last traumatic experience faced by Native students that semester.

On Saturday, April 30 of 2022, Red Territory — Yale’s inter-tribal drum group — traveled to Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts for a performance. As part of this trip, we were offered a tour of Andover’s Institute of Archeology, which we discovered was a Peabody institution — related to Yale’s own Peabody. After arriving at the museum, we quickly realized we’d walked into a large collection of “acquired” Indigenous items and ceremonial objects. Items removed from countless communities, many of which our own students belonged to, were kept in open storage boxes in unsecured rooms, locked away from the rightful owners. Witnessing this scene was a trauma in itself, a painful reminder of what colonial institutions like the Peabody have taken and retained from our Native communities.

Continuing through the museum, we were shown the ongoing archeological works in the building’s basement. Members of our group quickly realized the potentially traumatic threat that awaited us, but were reassured that the museum was not holding any human remains in its collections. This lie would create enduring trauma, as members of our community began opening artifact drawers, finding countless boxes full of human remains.

The consequences of spring semester were devastating on our community members. From the institutional violences following peaceful MMIW awareness to experiencing harm at the hands of a Peabody institution, traumas inflicted on individuals and the broader Yale Native community have remained with us and impacted many of our journeys. These traumas would contextualize the following months as our students ended the school year on a sour note at Spring Fling and returned in the fall to continued institutional ignorance.

May 2, 2022

After more than two years without Spring Fling, everyone was excited for the tradition to make a return and to find out the 2022 lineup. These sentiments would soon be ruined as it was announced that Masego would perform. This was devastating and frustrating news for the Indigenous community. We would not be able to enjoy Spring Fling without being reminded of the racism and oppression that Indigenous people face every day and how it often goes ignored.

Masego’s most popular song “Navajo” sexualizes Native American women, specifically Navajo/Diné women, and compares them to a “simian.” This is very harmful to the Native American community because the incidence of MMIW (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women) and sexual harassment of Native women remain prevalent and continue based on the sexualization of Native women and the commodification of their bodies.

NISAY tried to intervene and asked Yale if they could prevent Masego from performing this song. However, we were told that the Spring Fling committee had no control over what songs Masego could perform and could not disinvite him from performing. This was very frustrating to hear. The Spring Fling committee should take care in who they decide to invite and do research beforehand to ensure that none of the performers have offensive or racist songs. At a minimum, they should ensure that these songs will not be performed at Spring Fling.

We found some members of the Yale Spring Fling Committee’s lack of action unsurprising and indicative of the ignorance of Native American issues and culture that this institute currently holds. There is no reason why Native and Indigenous students should have to experience racism during Spring Fling.

What was most frustrating during this event was the lack of student support for the Native and Indigenous community at Yale. While protesting Masego’s performance, a couple members of our community took up space by playing drums and singing songs. Instead of welcoming the protesters in the audience, other students complained, shouted at or made vulgar comments and gestures to the protesters. Masego’s performance not only revealed Yale as an institution’s ignorance of Indigenous issues, but also that of the Yale student body.

Aug. 28, 2022

After a stressful spring semester, the Yale Indigenous community was excited for a semester of celebration, to hang out in the Native American Cultural Center and to form a stronger community, along with celebrating Indigenous Peoples Day and Native American Heritage Month. However, we returned to find out that our only place of solace — the NACC — had a newly installed security system armed at 12 a.m. each night. Not only would the alarm be in place, but, if triggered by motion, Yale Public Safety or Yale Police Department would come to the NACC to investigate who triggered the alarm.

Prior to the pandemic, the Native American Cultural Center was open 24/7. This meant that students could go there for late night studying or hang out with each other to form stronger friendships and bonds. Implementing alarms not only prohibits this community-building but also instills a system of policing on the cultural centers that is not at all inclusive — in fact, the opposite. This means that students who are not aware of the alarms may forget and in the worst case scenario cause Yale Public Safety or the Yale Police Department to come to the NACC. This would not only frighten the student but would also frighten the community with any actions that may be taken by YPS or YPD in their investigation of who is in the NACC.

Since the alarms have been put in place, everyone has been on their toes when it comes to staying in the NACC. Everyone on staff ensures that all students leave early so that no one has a potentially harmful experience with YPS or YPD. This creates conflict, because the NACC staff have to remove their peers from a safe space, putting an unfair burden on them and creating an uncomfortable power dynamic. We have also not been able to spend as much time with our friends or in community in the NACC due to the alarms.

Sept. 28, 2022

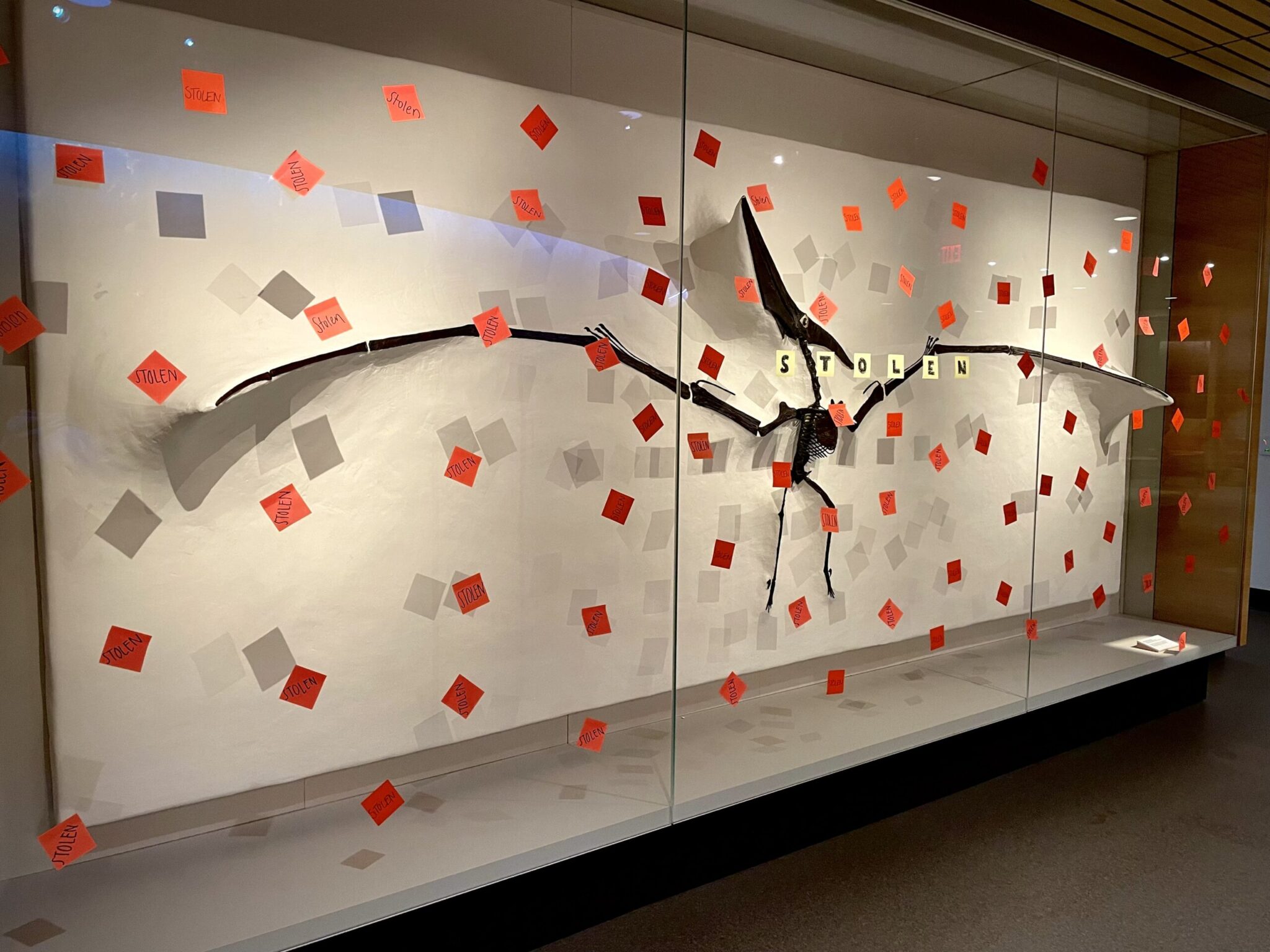

The Pterodactyl in O.C. Marsh was stolen from Indigenous lands. O.C. Marsh stole many articles from Indigenous people and lands. Stealing dinosaur bones or fossils from Indigenous people and lands may on the surface appear to be insignificant to those who were stolen from, but this is a deeper issue. Besides the obvious fact that stealing from Indigenous people is wrong, it steals potential avenues of wealth for tribes, and the process of removal of these fossils could destroy Indigenous lands. Fossils stolen from Indigenous people and lands ought to be repatriated.

To protest this, some Native students put red sticky notes on the Pterodactyl’s case that said “STOLEN.” There was no tampering with the sticky notes or using tape to stick them down. The sticky notes could be easily removed by picking them off as one normally would. There was also no vulgar language on the sticky notes. This was a simple, nonviolent protest.

Two days after this action, members of the Native community received a call from the Yale Police Department about the red sticky notes. In the call from YPD, the police said that a faculty member had called them unsettled about the sticky notes and viewed it as a form of vandalism. However, no permanent destruction was done and no tampering of the sticky notes occurred to make them difficult to remove. It was incredibly frightening as teenagers, students and Indigenous people to have our right to peaceful protest policed. Even more frightening was the method of identifying the students who had protested — their Yale Native shirts and facial ID.

As a community, we became worried about what we could do to peacefully protest. Were we always going to be policed or discriminated against in all of our peaceful protests on campus? There were no untruthful statements on the sticky notes and they could be easily removed. There was no violence or destruction of the cases to be categorized as vandalism.

The MMIW Vigil, the Masego protest and this protest all garnered responses that worried and traumatized Indigenous students. When are Native and Indigenous students going to be able to peacefully protest without being worried about our status as students on campus?

Oct. 10, 2022

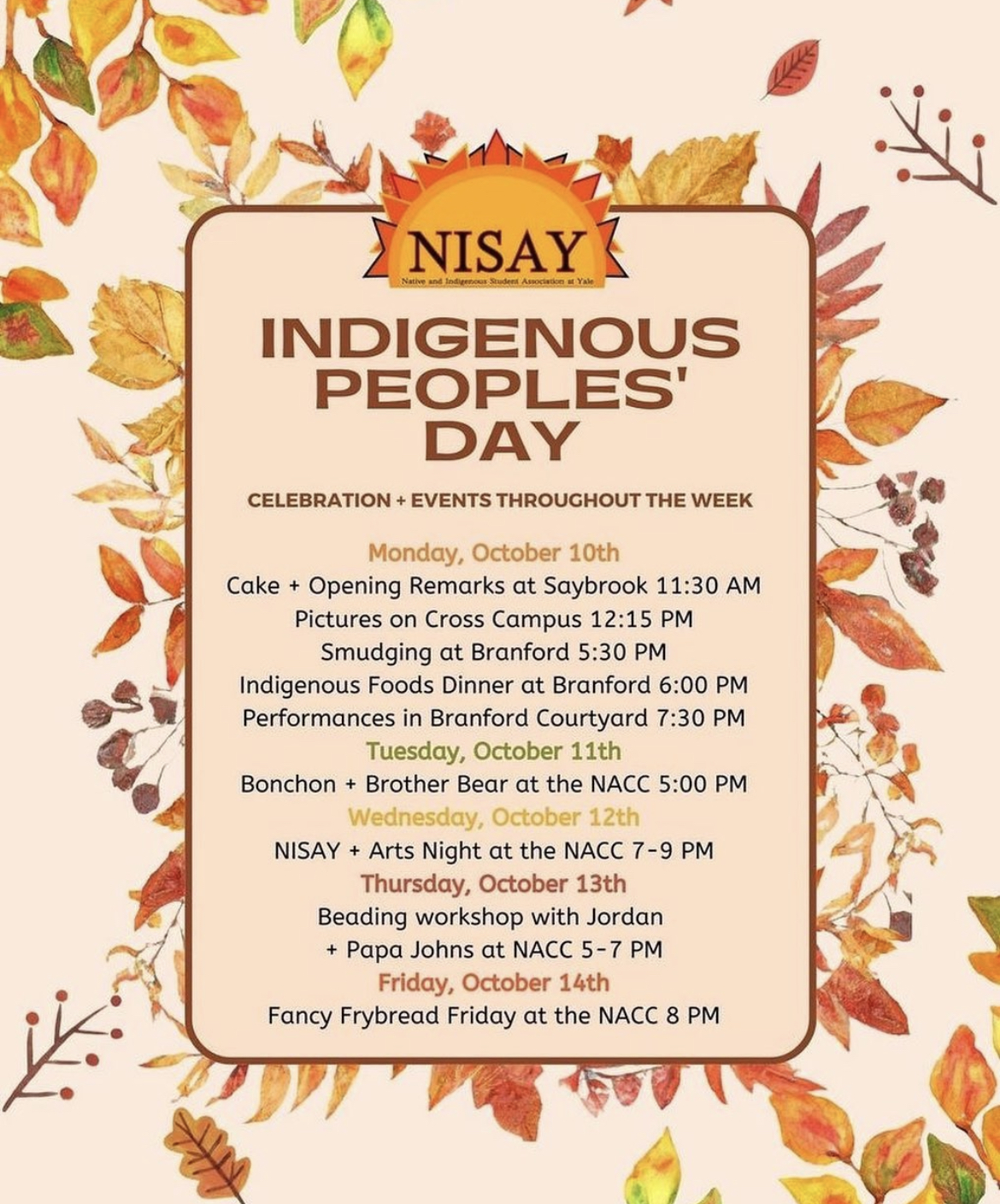

Oct. 10, 2022 marked an important annual celebration for the Native community at Yale, and for Indigenous communities around the globe. Every Indigenous Peoples’ Day (formerly known as Columbus Day in the United States) students gather to share music, dance and joy. For us, IPD commemorates the survival of our ancestors and our existence here today, continuing to fight for their stories and contemporary issues in our communities. It is at once a time of honoring, reflection and protest. Our community looks forward to it every year, and in the midst of a difficult 2022, we were especially excited for this year’s IPD.

Yale University does not commemorate Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Despite this, photos of our community celebrating headlined Yale’s official Instagram that day — from tokenizing portraits of students in traditional regalia to non-consensual recordings of cultural performances. Yale’s more than 665,000 followers heard our stories through the mouth of Yale, despite the university failing to honor IPD as a holiday. We call on Yale to solely recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day and to denounce the continuance of Columbus Day in the United States as an inherently harmful and racially violent holiday. While we appreciate the social media awareness, it is difficult to feel it as genuine support while Yale remains neutral in the fight for contemporary Indigenous justice and survival.

Secondly, an informative graphic on IPD events created by the Native and Indigenous Students Association at Yale (NISAY) was posted on the official Yale Instagram. Not only was NISAY not credited for the graphic in the post, but the NISAY logo was removed from the graphic. To our community, it felt like we were being erased from our own story. We call on Yale to properly credit Indigenous students for their hard work.

Ongoing academic challenges

To date, Yale has no Indigenous Studies major, despite having courses in Indigenous history that date back to the 1980s and over a dozen courses that are being taught currently. Other peer institutions, such as Dartmouth and Cornell, allow students to major or minor in the field. Prior to the fall of 2022, Yale College had only one tenured or tenure-track Indigenous professor. With the addition of two new wonderful professors last fall, students were excited to have new reasoning for an Indigenous Studies major. Even Indigenous students majoring in STEM tend to take enough classes about Indigenous people topics to fulfill a Native Studies major or certificate. However, we learned very quickly that institutional changes are never simple.

No matter how much demand there is, Yale requires professors, not students, to back the creation of a new major. With only three tenured or tenure-track professors within the College, we face the possibility of not having enough professors to advocate for creating a major. No matter how hard Native students work, they are thus unable to make tangible academic changes for themselves. We call on Yale to support their Native students in creating an Indigenous Studies major as soon as possible. Learning tribal and global Indigenous histories is an essential skill for all students, and this major would allow our community to thrive more structurally within Yale’s larger ethnic studies majors.

Every semester, students have the option to take Indigenous languages through the Native American Cultural Center’s language program. With accomplished and respected professors and a variety of languages offered, many students turn to this program to connect with their culture and practice their Native language. Yale, however, does not offer credit for these classes, despite them being organized and reputable. Unfortunately, taking on another full-time class without receiving credit for it is simply not feasible for many Indigenous students.

For many, the opportunity to learn their language from an elder has never been presented to them, and turning it down is very difficult no matter the additional strain put on them. For those who do take on the challenge, we’ve found ourselves struggling to keep up with other classes or with our Native language class to compensate for the constraints on our time and energy forced by this lack of accreditation. The reality is that students become forced to choose between their academic wellness and connecting with their cultures. We call on Yale to accredit the Native American Cultural Center’s language programs and provide support for them to expand. Alternatively, we call on Yale to expand resources for students to take Indigenous language classes outside of the University (for example, at their local tribal college) and count it towards the language requirement. Expansion of this would greatly increase Indigenous students’ academic health and capacity for cultural connection during their time at Yale.

Demands and changes we want to see

In order to make Yale a more welcoming and inclusive space for Indigenous students and Indigenous people in general Yale needs to change how they discuss and interact with Indigenous people. With this change Yale needs to collaborate with Indigenous leaders on campus (including but not limited to students, faculty, professors and local tribes) to make campus a better space for Indigenous people.

Yale needs to change their land acknowledgment. Currently the land acknowledgement uses past tense to refer to Indigenous people that were displaced. For example it says that the tribes “stewarded the lands and waterways” as if they do not currently exist or reside on their traditional homelands. The creation of Connecticut, New Haven and Yale led to the Quinnipiac not being a unified tribe that exists today. So, it is especially important to recognize the work the Quinnipiac’s descendants and the work of the descendents of the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic and other Algonquian speaking peoples do to maintain their sovereignty and connect with the land that Yale occupies.

Yale needs to recognize Indigenous Peoples Day and Native American Heritage Month. Yale currently recognizes Indigenous Peoples Day along with Columbus Day and Italian Heritage Day. This is paradoxical because Columbus caused the genocide of Native American people and actively committed violence and exploitation of Native Americans. One cannot simultaneously celebrate Indigenous genocide and Indigenous pride.

Yale needs to have an Indigenous Studies major. Many other colleges in the Ivy League offer a Native Studies major, such as Harvard and Dartmouth. Outside of the Ivy League many other colleges offer a Native Studies major, such as Stanford. Yale is behind on hiring Indigenous staff and creating a Native Studies major.

Yale needs to offer Indigenous languages for credit. Currently there is a program through the NACC that gives students the opportunity to learn their Indigenous language but the course is not for credit. This means that on top of their regular course schedule, Native students have to work harder to learn knowledge that was stolen from them because of colonization. The Linguistics department has taken steps to hire a professor that would teach an Indigenous language, but given that there are hundreds of Indigenous languages, this is not sufficient.

Yale needs to ensure that faculty are properly trained in cultural awareness, so that faculty are less likely to discriminate against, stereotype or oppress their students. Indigenous students have experienced racism and culturally insensitive remarks while in classes and by the broader Yale faculty. There is no reason why this should continue to occur at Yale. Increased formal anti-racism training should be the norm in academic spaces, and Yale is no exception. Students should not have to experience discrimination or racism in the classroom.

Yale needs to complete more thorough research and recognition of their hand in Indigenous genocide. There needs to be a formal investigation into how Yale and those affiliated with Yale contributed historically to the displacement and oppression of Indigenous people, including those who have lost fossils, cultural items and land to the University.

Ongoing Native success and joy

Despite the numerous traumas, violences and continued institutional shortfalls faced by Native students, our community also experienced a year of immense success, joy and growth. As marginalized communities have always done, we found strength in each other and our roots through difficult times. 2022 was defined by one of the largest ever number of first-years becoming leaders within our organizations and the NACC. Driven by this community growth, our organizations had great success in promoting Native voices on campus; from the MMIW Vigil to Indigenous People’s Day, NISAY brought us together and made the Yale community see, hear, and stand with Yale Natives.

In addition to these continued successes by our oldest organization, the Native community also saw the creation of new groups and events that are working to expand Native joy. The Yale Chapter of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society was reignited, and since then has ensured that Native students in STEM are represented, supported and successful on Yale’s campus. Additionally, with the rise of Indigenous Pacific Islander admits to Yale, the Pacific Islander Student Association at Yale was formed. Student leaders with support of the NACC created a first-of-its-kind professional development trip to Washington, D.C., where current Yale Natives could connect with Native alumni, practice professional development skills and gain insight into the opportunities available to Native students post graduation.

Finally, our students found personal success through community and leadership. Branford elected Nyché Andrew (Yupik and Inupiaq) as a YCC Senator, where she serves both the Branford and Native communities honorably. In the broader community, Yale gained two new Indigenous professors who work to create curriculum guided by Indigenous knowledge. These successes by our students, faculty and organizations have created an atmosphere of Native joy on Yale’s Campus, and Native students intend to continue thriving at Yale for years to come.

The future of Indigenous joy at Yale

Despite these challenges, Indigenous students have been finding ways to thrive on campus for more than a hundred years. In times of harm and struggle, we rely on each other and the strength of our ancestors to carry us toward a brighter future. Walking around campus, whether in jeans, beadwork or a ribbon skirt, we are connected many layers deep by something much larger than ourselves.

This year, we are looking forward to a couple of very large celebrations, and invite you to celebrate with us. Please come to the Yale 2023 Powwow on April 22 to share space with us and elevate the beauty of Native American joy. There will be food, lots of beadwork and dancing. This fall is the Native American Cultural Center’s 10th anniversary, commemorating a decade of having our own physical space on campus at 26 High Street. We will also be hosting the Henry Roe Cloud conference in memory of Henry Roe Cloud, the first Indigenous student at Yale. We honor those who have come before us, our peers now, and those who will come after us.

We bring you these stories as leaders, organizers and carriers of a legacy of resistance. Our experiences this past year have strengthened us and our communities — our resolve as Indigenous people to make a difference is unwavering. The Yale Native community will be busy in 2023 making our voice heard on campus; we call on the broader community to amplify our voices and to support your Indigenous peers.

Madeline Gupta ’25 – Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

Mara Gutierrez ’25 – Navajo Nation

Jordan Sahly ’24 – Eastern Shoshone Tribe