Jessai Flores

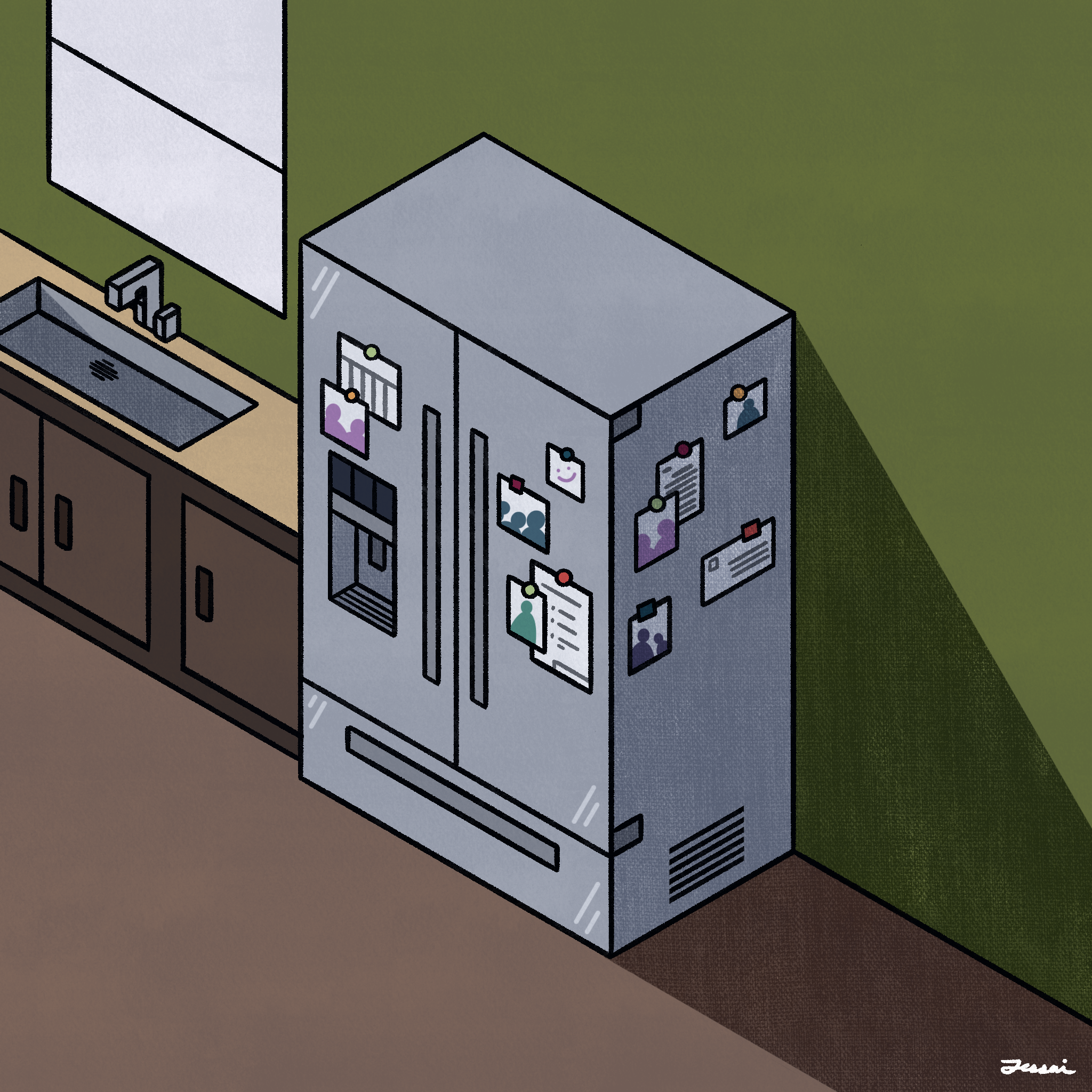

The refrigerator in my kitchen is a coffin of memories. It juts out from where it is lodged between the bit of granite countertop at the end of the sink and the vacant negative space of the avocado-green wall where my mother once tried to hang Tuscan-themed wall decor she bought from an internet antique store. The avocado wall—unsightly, my mother had told my father when he had painted it — could not bear anything placed upon it. Unsightly. A wall in a home of a family of seven, and it never carried any evidence that anyone had lived there. Instead, the refrigerator — scarred by its years of loyal service — was pockmarked with magnetic dots and squares that fastened onto it the moments of my family’s life like medals on a general’s lapel. Every visit to the refrigerator was a visit to the altar of my childhood — and then some.

To fetch the carton of orange juice was to confront — there on the corner near the hinge of the right-hand door — a picture of my sister and I as children playing with a plastic shopping cart and a baby doll. She wore pigtails. I wore bushy eyebrows arched in surprise. Perhaps, we were playing house in the narrow hallway of the childhood home that was not ours anymore. Behind us loomed a television set, the kind before they became flat and artificially intelligent. That television ended up on the curb when our family outgrew that tiny two-bedroom house. It was the kind that was too heavy to carry and yet the refrigerator carried everything and all of us. Nostalgia, is it? Hanging heavy like condensation on the doors.

Below that picture of my sister and I, a portrait of Barack Obama the size of a King of Hearts. I was in second grade when he walked into the White House and in tenth grade when he moved out and into our home. Now, he stands with his arms crossed glaring at me from above the indentation in the metal of the refrigerator door where someone — one of my brothers perhaps — learned why we do not play catch indoors. The Obama years and what came after are a hallmark of the childhoods of my generation. I meet Obama’s gaze and I am brought back to the robotics competitions in middle school, the bus rides home after school, the smell of leaf piles in the fall. I grew up much too quickly, much too soon. I remember listening to Lady Gaga on the radio when she was new and when she terrified us with her dresses of meat and blood-red diamonds. Now you hear her on the throwback stations. The longer I think of the past, the more I get lost in it. Human memory is fallible. I cannot remember everything as it was. The pictures on the door help me start the engine in my mind and I get to meandering within the incomplete scenes of the life I remember. By this point the orange juice will have grown warm. Nostalgia. What a waste of time.

Yet to look at Obama or at any of the mementos on the refrigerator doors, is to be transported partially into a sweetened version of the past. That strip of photo booth pictures of my mother and oldest sister by one of the door handles? A portal into our time at the Lego convention in Fort Worth my mother had surprised us with when we were in middle school. I had the time of my life. The picture of my youngest brother covered in silly string? A look into the mess he would make as a toddler in the backseat of the old family minivan — the silver one before it was totaled by a woman going much too fast. And that selfie that was printed out and tacked onto the refrigerator door above the built-in water dispenser that does not work anymore? A moment from my fifteenth birthday just after a big dinner at an old-fashioned burger diner like those from my grandparents’ time. The dinner was delicious. We do not eat there anymore. My father never liked the way they cooked their meat. These pictures are proof that the past I remember did happen. They are little snippets of truth held in place by magnets. Investigate one and the memory unfurls — albeit a little different each time, but the picture contains the facts of it all. I wore a blue shirt with a white motorcycle in that picture outside of the diner. That is a fact. Whether the cheese on my birthday burger — if there was one—was cheddar or American, I will never know for sure. Nostalgia is silly like that. Making us remember everything but not entirely. Giving us a picture, a point of reference, and telling us to paint in the rest with our imaginations.

On bad days, I like to pretend that I am the child standing in that narrow hallway with his sister at his side. I will wish to be as unchanged, as innocent as he was. I will close my eyes and imagine life before I knew what the words “ontological,” “insurrection,” and “calculus” meant. I will wish to be young and do it all over again. And yet I open my eyes and find an adult staring back at me from the reflective surface of the refrigerator doors. I am an adult now and how sad it is to be yearning for the past while holding a carton of juice I no longer want. Perhaps that is the beauty of a childhood well spent. A childhood so good that it makes you sad to discover that it has ended and you can never go back. Nostalgia, that great pain of remembering the good times. The sweetest that pain can be.