Yale researcher highlights racial ethnic bias in school disciplinary practices

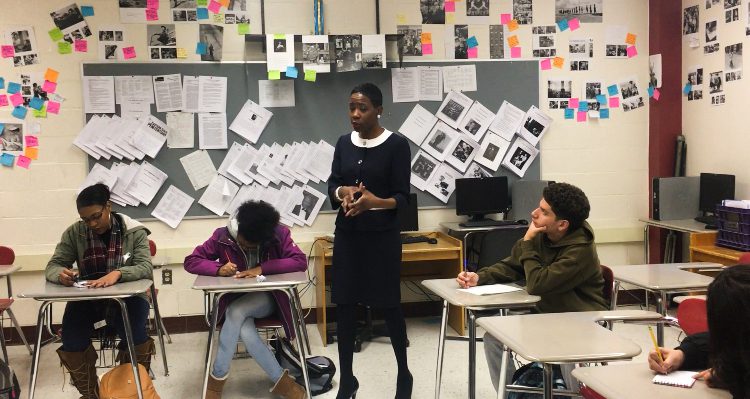

Jayanti Owens’ recent research explores the nuanced relationship between students’ race and how teachers respond to misbehavior.

Isabel Bysiewicz

Jayanti Owens — an assistant professor of organizational behavior at the Yale School of Management — recently published research that finds that a student’s race and school culture play a factor in how teachers respond to misbehavior.

The study, titled “Double Jeopardy: Teacher Biases, Racialized Organizations, and the Production of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in School Discipline” focused on identifying the source of the racial disparities in school punishment with an innovative approach. Although racial disparities in disciplinary actions in the education system have been documented, the fundamental causes of why students are treated differently have not been adequately examined. Owens’ approach showed teachers videos of teens from different racial and ethnic backgrounds misbehaving through behaviors such as slamming a door and texting during a test.

The research included 1,339 teachers in 295 U.S. schools, taking into account the schools’ racial/ethnic and socioeconomic composition. The experiment sought to determine how factors such as teacher bias and school climate drove discrepancies in student discipline. The research focused on teenage boys, since Owens found that boys are disciplined more frequently than girls, particularly in high school.

“We find that black boys face a double jeopardy in that they are both perceived as being more blameworthy for the exact same behavior as their white and Latino counterparts, and also that they’re more likely as our Latino students to attend schools where teachers perceive students from all racial, ethnic backgrounds as being more blameworthy than do their counterparts in predominantly white schools,” Owens said. “There’s this sort of double disadvantage that is faced by black students in particular.”

Through this method of showing video vignettes of students engaging in the same behavior, Owens concluded when Black actors behaved the same as white actors, teachers were more likely to refer them to the principal’s office — demonstrating the pivotal role of the teacher’s decision-making in the impact that this has on a particular student.

These findings suggest the various causes for higher referral rates of minority students, which can lead to unfavorable outcomes for the student, such as detentions, suspensions and expulsions. The dynamic between the student and the teacher is vital in understanding how and why there are disproportionate outcomes in student punishment.

“People jump to the conclusion that just because there are disparities, that there is, in fact, racial bias in disciplinary decisions,” Owens said in highlighting the importance of this study. “In order to be able to claim that there’s racial bias at play, one needs to understand that you have students from different racial, ethnic backgrounds engaging in the exact same behavior.”

Another point that the research demonstrates is that the school environment is an important factor in determining how likely a student is to be disciplined for their behavior. Teachers’ reactions to misbehavior varied from school district to school district — teachers were more likely to place blame for misbehavior on all students, regardless of race or ethnicity, when there were a disproportionate number of students from underrepresented groups in their schools.

Owens emphasized the importance of reconsidering current discriminatory practices in the administration of school discipline punishments. Although teachers play an important role in disciplinary processes, blaming teachers for being biased towards students should not be the case in resolving issues related to school discipline, he said. Instead, he advocated for adopting a holistic approach to work towards mitigating the ramifications of racial biased disciplinary practices.

“I think that we need to take a systems-based approach to thinking about how we can reduce these racially biased sort of incidents within classrooms by thinking about the structure of schools overall,” Owens said. “Other districts have actually tried to reform discipline processes altogether through the use of things like restorative justice practices, that are aimed at trying to mediate conflict when it arises between students and teachers or between students themselves.”

Mira Debs, Executive Director of the Education Studies Program, spoke about the importance of this research’s findings and how disparities in school punishment outcomes can have long-term consequences for students. In all cases, the relationship between a student and a teacher should strive for conflict resolution and ensure that the teacher is empowering the student, Debs said. Nonetheless, students in school environments where disciplinary processes disproportionately impact them may experience the negative consequences of these measures.

“When a student is frequently being disciplined it can negatively impact their sense of self as a learner,” Debs said. “It can also make them feel like they’re going to act in opposition to school because there’s no point in continuing to try. This often gets talked about as being part of the school to prison pipeline. So students who start getting referred into the disciplinary system continue to be progressively referred more and more and that can lead directly into students going into the juvenile justice system.”

Richard Lemons, executive director for the Connecticut Center for School Change and lecturer in education studies, and Leslie Torres-Rodriguez, superintendent of Hartford Public Schools (HPS) are co-teaching a course this semester titled “Educational Design: The Form and Function of Schooling and Learning.”

“I think we’re still struggling with exactly how to do this, how to deal with this because I think [these kinds of studies] reveal that it’s inside people’s judgment call these thousands of moments a day where an adult is making a decision, is drawing inferences reaching a conclusion about something that involves a child and and what are the negative consequences on the child’s — it’s a really complicated issue,” Lemons said.

Lemons spends most of his time running a nonprofit that collaborates with school districts to help them achieve instructional improvement and addressing issues of equity. There are always opportunities and ways to improve public education through research and supporting the next generation of educational leaders, emphasized Lemons. His time as a visiting professor through the Yale Education Studies program has been rewarding as he aspires to teach his courses with the central vein of equity.

“The course that I’m teaching this spring along with my colleague who happens to be the superintendent of Hartford Public Schools, similarly has a main vein. An explicit tenant running through the entire course, is around equity,” Lemons said. “So we’re asking questions all the time about what are the needs of the end user, students and parents? How do we know what the problem is that we’re trying to solve? And how do we prototype ideas? How do we develop creative ways of solving them and then test those ideas?”

Torres-Rodriguez leads HPS, one of the largest urban school districts in Connecticut, and aims to ensure that her school district can provide the best education to all students. Like most issues within education, school discipline is complex and requires Torres-Rodriguez to foster a school culture that meets the needs of students, staff and families.

“HPS utilizes a Restorative Practices approach to disciplinary practices in all schools,” Torres-Rodriguez wrote to the News. “HPS believes that students need to learn specific skills in order to positively resolve an issue or appropriately respond to a peer or staff member. The reason for the targeted learning and practice is not only to model, but so students build their toolbox of responses.”

Although the challenge surrounding school punishment and discipline requires numerous individuals and stakeholders collaborating, Torres-Rodriguez said, “Building positive relationships with our HPS students is at the core of our work, and should be in any organization that serves young people.”

Owens’ research paper can be found here.