Jessai Flores

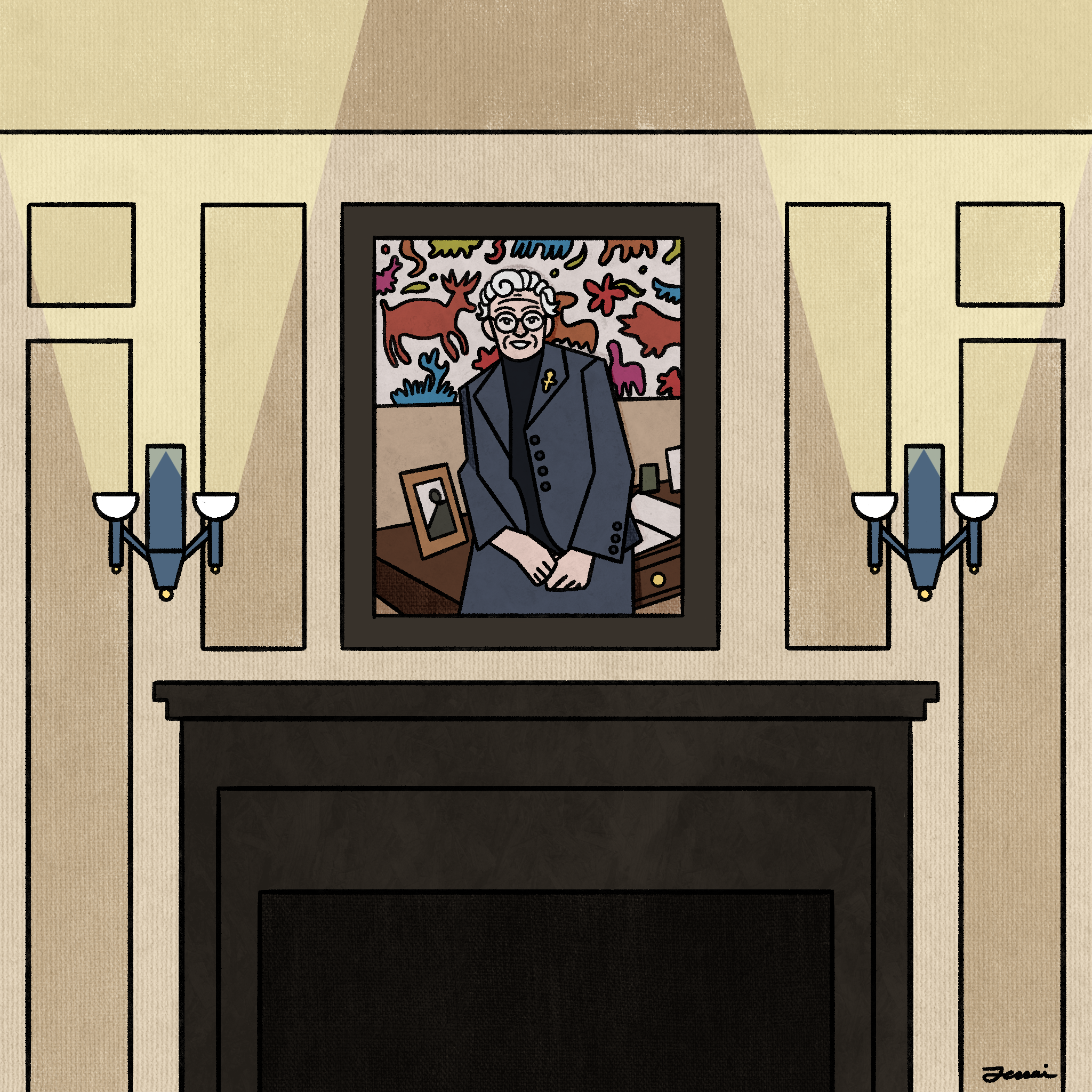

On Thanksgiving Day, I danced with the portrait of the woman in blue who was hung over the mantle of the Davenport Common Room. She was as old and as dead as many of the other painted people on the walls of the University. But there was something to be said of the liberation I felt to spin top-like in a reckless beeline around the stuffy hotel furniture of the room. I spun and spun as she looked down. Down through her block glasses, following the arrow of her sloped nose and to the dirty carpet beneath her. Was she lonely? I wondered. Perhaps she was, but was not everyone who came before and after her?

Yale has a reputation of being lonely and loud, protruding from the center of the city like a cathedral to education. It is a collection of gothic spires where legacies are remembered, tended to, and forged by generations of pupils according to rules written and rewritten across the institution’s many years. In these years, there are small gaps in the University’s phonographic record of loud student life. The recesses, the breaks and snaps in the sounds of Yale’s history, occur when the voices and cheers subside and a salve of silence fills the vacuum left behind. Those of us who stay during the breaks, like me and the woman in blue, are given a rare sight: a Yale that is quiet but not lonely.

It is true what they say about never knowing what you have until it is gone. This idea has haunted me this semester. It is my last year at Yale, and I have kept myself busy tending to the garden of my many commitments: pruning the roses of my readings, organizing the lilies as paper-white as all the canvases I had to fill as an illustrator and swatting at the aphids of procrastination that ate what I had planted. Anything to keep me hunched over my plot with my back to tomorrow. A cloudy tomorrow that would usher in the spring and its commencement, raining down caps that would bid my class farewell for the last time. I do not like to think about it — graduation and having to leave this place. This year’s Thanksgiving Break, my last one, forced me to contend with this place and the beauty of it that I got to enjoy. And Yale is beautiful. I let the silence of the empty campus fill in the noisy corners of my memory that had been slanted by the pressure to perform. So, I looked up, and I spent my break waltzing among Yale’s many oaks, screeching out songs in silent rooms, and taking in its history. I never knew what I had until my commitments were postponed, and I could enjoy time to myself.

The silence is not lonely, though it can be if you choose to resist it. You have got to learn to sing with it, to fill it with a quiet appreciation for what you have. Is that not what the spirit of Thanksgiving is: a ritual counting of blessings? The break afforded me a cornucopia-like silence for me to fill with the thanks I gave for the honor of a lifetime — of getting to be a student here — and its many quiet moments of reflection and joy.

There is joy in the life of things, and the silence of the break allowed me to recite its praises by enjoying the time I was afforded to be alone. I meandered through the many overpriced boutiques on campus, like the one by the ice cream shop that sells beige sweaters for three-hundred dollars, and pretended that I was a rich man and there was joy in that. I manned the reference desk at Sterling Library, the one place where the silence was filled with the noise of tourism, and I ate donuts with my desk partners — there was joy in that too. There was joy in the leaves I crunched beneath my heels, in the laughs over sticky packing tape that I shared with the mailwoman at the post office, in the blush of my face braced against the cold, and in the circles I spun in front of the woman in blue.

Joy! In the lives of all the things! Staying behind on Thanksgiving is a joyful type of loneliness, full of the things called memories and friendships and telephone calls with loved ones. To stay behind is to see the blanket of silence hush over the cupolas, cross braces and eaves of empty campus buildings — and to see this place come to life again when it is all over.

When the break ended and the noise of students burst from the trumpet-mouths of airport shuttles and taxi cabs that dropped their cargo outside Phelps Gate, I was satisfied with the knowledge that at least I had the week to enjoy the University alone. To walk its many corridors and make note of its many joys. But I was also relieved to be once again surrounded by my peers because there is joy in that too. During the break, I savored the leisure of being alone, of swinging on the swing set behind the Lock Street parking garage and dancing under the fixed gaze of the woman in blue whose smile was painted upon her face. She, too, knew of the joy of things. The night after the break ended, someone played Mozart on the common room piano, and my sly eyes met the frozen ones of the woman in blue. We smiled because even as the old dramatic performance of Yale life continued as if it was never interrupted, the secret of Yale as a place of quiet joy was something only we — and you now — know.