Dora Guo

Mildred, Maude and Mabel

Were sitting at a table

Down at the Taft Hotel

Working on a plan to

Catch themselves a man to

Satisfy their minds a spell.

For twenty years and then some

They’d been showin’ men some

Tricks that made their motors fail,

But though they’d all had squeezes

From lots of PhD’ses

They’re saving themselves for Yale.

Hail, hail, hail to the boys down at Yale

– Saving Ourselves for Yale

At Yale, we love love. And nowhere loves love more than the WKND desk of the Yale Daily News. We love to write about it. We love to think about it. We love to do it, whatever “it” means. Love, sex and dating are eternally emportant. However, what is less eternal are the rituals, traditions and unspoken rules of courting. In fact, dating has changed dramatically over the past 50 years.

Seven Sister Schools, Strict Rules

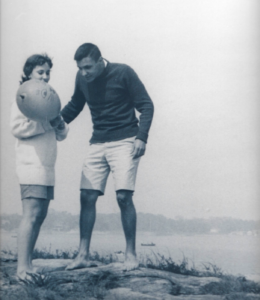

In his senior year, Raymond Crystal’s ’60 roommate gave him the number of a Sarah Lawrence student named Laura Barr. After carrying her number around in his pocket for a while, Raymond asked Laura to see Yale face-off with Columbia. Yale would wait a decade before letting women into the college, therefore the standard courting practice was for a man to invite a date to take the train into New Haven for a football game. Unfortunately, Laura turned him down because she already had a date for the night. Instead, she invited him to her home in Mount Vernon for the afternoon where they discussed The Republic. Laura was smitten and called off her previously scheduled date for the evening. Within the year the couple was engaged on East Rock. When Raymond went to medical school, they eloped in a Harvard chapel.

Raymond and Laura Crystal have been married for sixty years. When I met them on a Zoom call, they sat close together, thick as thieves, ready to tell me about their romantic history on Yale’s campus. To me, their story seemed like a Disney fantasy, but Mrs. Crystal insisted that Yale was “180 degrees different from what it is today.”

Austere. Testosterone. Academe. These words she used to describe campus. The woman a Yale student dated was “not allowed to participate in life at Yale.”

Dating structured around the football season. Women would come up on the train from various women’s colleges including “The Seven Sisters” which consisted of Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke, Smith, Radcliffe, Vassar and Wellesley. “It was like an exodus on Fridays,” Mrs. Crystal said. “We’d all get on the trains with our little suitcases. We would say ‘Where are you going? Where are you going? Where are you going?’ … We’d all get off at the train station. We’d all share taxis to Phelps Gate. We’d go our separate ways.” Women couldn’t stay in the residential colleges so men would get them rooms at the Taft Hotel or the Old Park Plaza Hotel (now the Omni Hotel). Men could also check women into guest rooms in the Head of College House. Secret societies would put women up, although this was not looked on as “the thing to do.” Strict parietal rules, enforced by small police stations at residential college entryways, regulated the sexual relationships at Yale. According to Mrs. Crystal, women couldn’t just come and go. A guard had to take a woman’s name, ask where she was going and escort her there. The door had to remain open and women had to sit in a chair. If they sat on a bed, one foot had to be on the ground. Guards went around to make sure couples were behaving. “You could not have sex in a residential college,” she said.

While broken rules could result in expulsion, some couples still took their chances. Mr. and Mrs. Crystal jointly recalled that one couple snuck past the guards by hiding the woman under a trench coat, fedora and varsity scarf.

Mrs. Crystal also recalls other strange rituals to acknowledge the rare presence of women on campus. For example, men were required to wear sports jackets to the dining halls and bring their silverware. “If a woman entered the dining hall everyone would take out their forks and pound on the table.” she said. “Relationships between men and women were very unnatural” and “women changed [the culture] a lot very quickly” after coeducation.

Coeducation Splits a Dating Culture

According to Professor Jay Gitlin ’71, up until coeducation, life at Yale “was like living in a monastery.” When the first women arrived, however, the monkish lifestyle dragged on. Gitlin described a sense of “duty to be gentlemen and treat them like sisters.” While there wasn’t much dating between the new coeds, relationships with women from sister schools persisted.

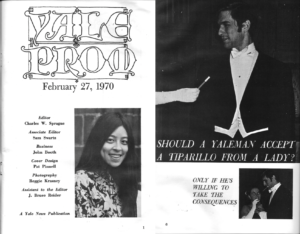

My conversation with Professor Gitlin painted an idyllic picture of a warm, predictable and romantic dating cycle. Women would come down on the train to meet a Yale man and go to a football game, followed by dinner and a mixer with a keg. He described that on a Saturday night you would walk down Elm street and hear live music playing at every college. The social season culminated in the Yale Prom where Gitlin, a professional musician, remembers Wilson Pickett playing the hit song, Mustang Sally.

“Dancing was very important.” Gitlin said. “Dancing was as close as you got.” In an era of first-base, second-base and so on, “there was absolutely no assumption whatsoever that you were going to be rounding the base paths,” he said.

“By the time you held hands,” Gitlin added, “that was damn exciting … If you wound up kissing that evening it was like: Wow, how great was that!? … Then you went back to your class on Monday.”

The dating cycle reserved for weekends and football games only allowed Yale men to see a woman they were interested in a handful of times a semester, but Gitlin said that this did not prevent real connections from being made. “It was romantic!” He said. “Anticipation has something to do with romance.”

Harvard men were stereotyped as stuck up, and Princeton men were seen as nerdy. Yale men, on the other hand, were seen as the best dates. “We were good boyfriend material.” Gitlin said. He told me he wondered if “there were any good guys around here for you all.”

When I asked him about the free-love movement of the 60s and 70s Gitlin assured me Yale culture was a far cry from Woodstock and that he didn’t believe there was a heavy drug or hookup culture. However, Dr. Dori Zaleznik ’71, a transfer student into the first class of women at Yale and the first woman on the masthead of the Yale Daily News, described a completely different picture. “Oh, there were drugs.” she said. “My sense was coeds didn’t do much dating … while there were certainly women in our class who met their now husbands at Yale … the majority of women didn’t formally date in that kind of dress-up-and-get-taken-out-to-xyz way.” Zaleznik said.

She also deviated from Professor Gitlin in her conception of Yale’s sexual culture. “The whole sense of ‘you’ll get expelled when you let a woman in a room’ dissipated after we got there,” she said. As a result, the concept of hooking up was born on Yale’s campus.

Zaleznik emphasized that there were many strands to social life, among which existed a big cultural divide. Traditional social scenes that prioritized drinking were challenged by new social groups whose congregational sacraments were marijuana and other drugs. Zaleznik, who participated in the latter, knew about the prom but did not go. As for movies and football games, she mostly attended those with her friend groups.

But beneath the rapidly evolving social scene, a bigger obstacle was hidden for Yale’s first women. As a stark minority in a deeply gendered culture, they were much more preoccupied with finding equal footing with their male classmates. Zaleznik recalled her first morning at Yale. When she went to breakfast, the number of women in the dining hall was so small that the only seats available were with large groups of all men. “One guy hopped up, nearly knocking over my tray to pull out my chair,” she remembers. “There were a number of men who didn’t know what to make of all of us.”

She remembered another experience, of going to a football game with a potential date. “Having grown up with a brother who was into sports, I knew a lot about football. I was sitting there at the game and the Yale team got punted. We got a good run-back but then there was a flag.” Zaleznik quickly identified that the flag was a penalty for clipping, now known as “block in the back.” “The guy that I was with looked at me like I had five heads. It was clear that I was not supposed to be a sophisticated observer,” she said. “Needless to say I did not go out with that guy again.”

Unfortunately, up until this point in history, the overwhelming number of visible love stories were those between a man and a woman. What Zalzenik and Gitlin did agree on was that any sexual minorities were not visible. “It was still not an environment where people were very comfortable coming out.” Zalenik said. She guessed that this changed over the next five to 10 years.

Dealing with Diversity

By the 1980s there was much greater acceptance of LGBTQA+ identities. According to Dr. Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas ’90, a youth culture specialist and Chair of Ethnicity, Race and Migration, many students were in the process of coming out in college. Professor Ramos-Zayas was not queer herself, but she recalled that “There was a queer dating scene,” and in her circles there was a strong Latinx queer dating scene. The AIDS epidemic also had an effect on sexual culture. She said that while people did hookup, “there was this t-shirt that said ‘Sex kills. Go to Yale and live forever.’”

Besides, there were also socioeconomic, ethnic and racial determinants of dating. The way people dated, commented Ramos-Zayas, “varies by class. [It also] varies by race and ethnicity, how emotionally ready you are.” As a Puerto Rican immigrant who was heavily involved in the cultural houses, she remembers that everyone in her friend group was busy at Yale. They were balancing multiple jobs, culture shock and homesickness. “It was kind of survival mode,” She said.“I think for us it felt like Yale was a lot of opportunity. There was opportunity to play volleyball. There were opportunities to go to political events. There were mentorship programs with the kids from Wilbur Cross Elementary School. There was so much to do,” she said.

When I asked her about what actions she would take in the presence of romantic feelings, she said, “We had crushes on people all the time. We talked about it with our girlfriends endlessly.” But those talks were less about romantic relationships. Instead, “it was a bonding experience with girlfriends,” she said, “rather than a serious source of desire.” While she could recall a handful of couples, she said that “there was not that sense that this is where I will meet the love of my life.”

~Modern~ Dating

On the surface, the sentiment that you won’t find true love at Yale seems popular. Casual sex and disposable dating app matches are common. Under this surface, however, many students feel a heaviness in modern dating life. According to Tyler Brown ’23, “If you’re looking for a relationship — which not everyone is, people are preoccupied with the emotional support and growth aspects of it. […] The trauma dump is a Yale tradition. […] Everyone is talking about their attachment style. […] There is an emotional tinge to everything. […] The Yale personality is very nerdy about dating.”

In a culture where TikTok influencers promote pop-psychology, it’s clear that “the world has learned more about psychological health, and it’s been distilled and people hear these little phrases. People rely on that to understand their romantic attraction,” Brown says.

However, for the subset of Yale that isn’t looking for a relationship, dating apps and a casual culture surrounding sex “provides a cheap rush of dopamine,” according to Brown. He says the dynamic of “I value you for this moment right now but I don’t value you for any other moment is pervasive. It manifests itself in romantic and non romantic settings.”

Brown also highlighted a “weird power-play” that occurs over dating apps. “The problem with Yale Tinder is that we’re small enough to recognize [your matches],” he said. Some people have the confidence to swipe on friends while others don’t.

While Professor Ramos-Zayas says she didn’t notice much of a difference in approach to how people of different sexual orientations built relationships on campus, Tyler Brown ’23 suspects it’s “much easier for straight people to go out find someone [and] have sex with them.” Although Brown did meet his current boyfriend at a fraternity, he felt that this was “incredibly rare” for a gay couple.

“As a straight person you don’t have to worry about your presentation in the world,” he said. When it’s tricky to figure out if someone you meet is gay or not, Brown says there is a secret communication that occurs. “You let down your guard a little bit or use a different voice and see what the response is. […] I was once told I had a really gay Spotify because all of the music was strange and unbearable. […] Telling someone that you listen to Mitski is a big rainbow flag.”

The modern paradox of yearning for both fast and deep connection, both easy and fulfilling love, is a hard one to solve. However, while I interviewed Yalies across generations this past week, it seemed as though love has always been a confusing, ever-evolving and eternally important pillar in our lives. Most importantly, the alumni that I spoke to seemed to thoroughly enjoy reminiscing about the highs and lows, break ups and down bads, the hookups and honeymoon phases. So no matter what chapter of your romance story you’re in, perhaps it is wise to revel in it at full force. Soon it will all be history.