Acknowledgement of racist past just the start, Yale Divinity School students say

The Divinity School recently recognized its historical complicity in slavery and racism and laid out concrete steps to move forward. But students long for more.

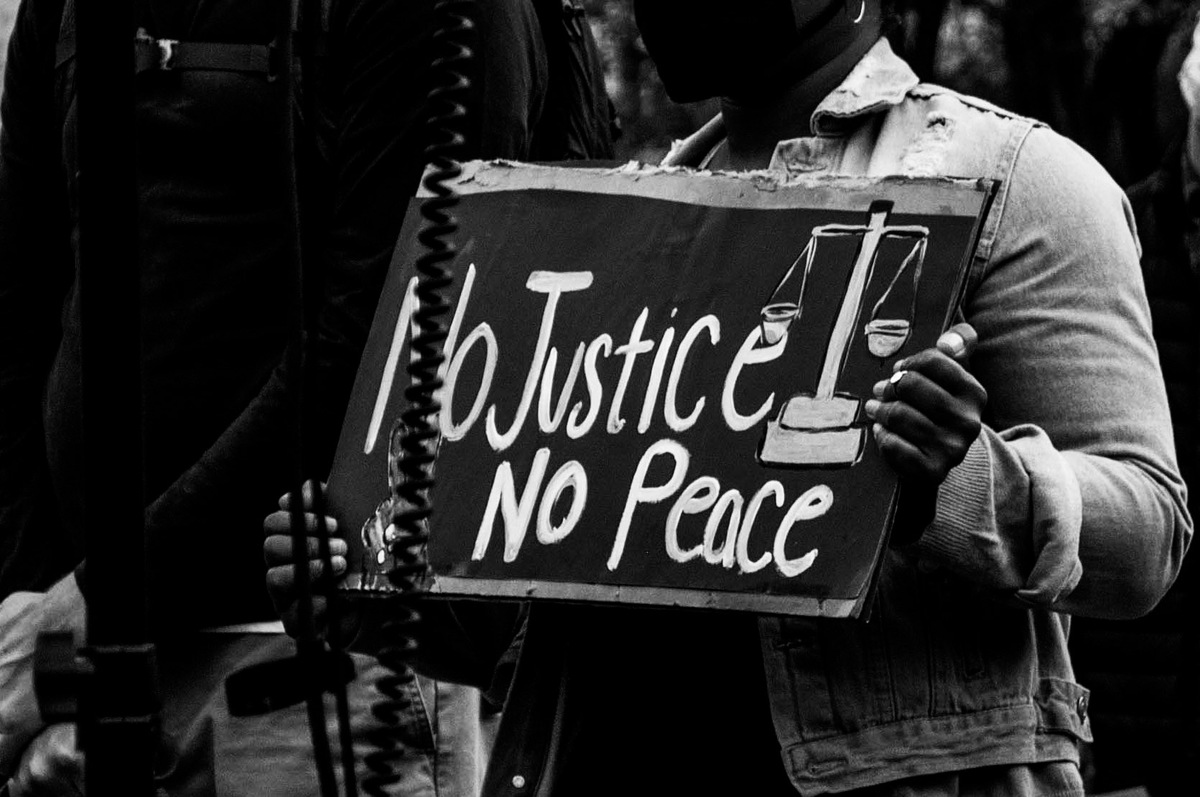

Pranav Senthivel. Contributing Photographer

In December, Yale Divinity School Dean Greg Sterling officially acknowledged the school’s historical complicity in racism and announced plans for change. But, according to students who spoke to the News, there is still a long road ahead for true inclusion.

Sterling’s video announcement on Dec. 16 presented a number of main actions, including the allocation of $20 million of the Divinity School’s endowment to fund 10 full scholarships for students pursuing social justice, and asked for “forgiveness” for the school’s darkened past. The announcement came as a result of recommendations made by the Divinity School’s anti-racism task force, set up by Dean Sterling after the murder of George Floyd by a police officer.

“[We] ask for forgiveness [as] a way of signaling … that we’re serious about trying to make changes, to indicate that we recognize things have not always been what they should have been,” Sterling told the News. “I don’t think you can ask for forgiveness without a form of repentance.”

For the past 10 years, the Divinity School has embarked on a mission for inclusivity. Honoring leaders of color in the institution’s history, increasing diversity in faculty and staff and attempting to promote a sense of belonging for all students have been pillars of the school’s work so far, according to Sterling.

In 2020, these efforts were amplified, and the anti-racism task force was established. Led by associate professor of systematic theology and Africana studies Willie Jennings and professor of New Testament criticism and interpretation Laura Nasrallah, the task force included a diverse array of students, faculty, staff and administrators — including Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Lynn Sullivan-Harmon, who spoke about the school’s long term equity plan in the video announcement.

The group produced 27 recommendations to increase belonging on campus, four of which were addressed in Sterling’s announcement, although he told the News that many of the others have already been put into place.

But, for some students, these actions left them wanting more. Jyrekis Collins DIV ’22, the acting president of the Yale Black Seminarians, a faith-based Black student group devoted to justice, told the News that he believes that historically, the University has always tried to do the bare minimum, and students are left to lift the heavy burdens for change. While he commended the work Sterling, Jennings and Nasrallah are “striving” to do and believes they are doing an “amazing job trying to address the issues at hand,” Collins said he feels there is still a long way to go.

“I think that I echo the sentiments of Yale Black Seminarians and people of color and YDS students as a whole, that we really want to see more.” Collins said. “While [Dean Sterling’s] response was a start, it’s not enough.”

In addition to the social justice scholarships, Sterling announced that $2,000 research grants will be given to 10 students each summer to pursue research related to social justice. There will also be funding for students to attend the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, a group of clergy, thought leaders and seminarians committed to social justice who gather annually. The Reverend Frederick J. Streets Prize will be established and awarded to a graduating student each year who has been deemed to have made a significant contribution to the advancement of social justice.

Nasrallah emphasized that scholarships and stipends were a “high priority” for the anti-racism task force and told the News that these scholarship and funding opportunities fit in with the idea of reparations.

“The economic structures in this country are still being lived out with the racist after effects of slavery,” Nasrallah said. “I really think that the scholarships and stipends are incredibly important, and that they can be a reparative act.”

For Sterling, the $20 million social justice scholarship fund is an act to welcome Black students to the Divinity School. He said that in taking this action he thinks back to Mary Goodman, a Black washerwoman and entrepreneur in the 1800s who left her entire estate — $5,000 — to the Divinity School so Black students could attend, enabling the first Black student to graduate in 1874.

“There’s a sense in which this is an attempt to imitate what Mary Goodman did in the 19th century. And, but to do it now in the 21st century,” Sterling told the News.

However, for Jathan Martin DIV ’21 GRD ’27, framing the scholarship fund in terms of social justice gave him “pause.” Martin explained that for the precedent to be that Black students have to pursue social justice to earn these funds is one that puts an “undue burden” on Black people, one that white students do not have to bear, since they are not expected to center their work “around their livelihood.” Martin said that this “saddens” him, especially as Black students come to the Divinity School with a wide range of interests.

Sterling’s announcement also focused on the acknowledgment of the Divinity School’s historical ties with slavery and racism. He spoke about Jonathan Edwards, an alumnus of Yale and a distinguished American theologian, who owned several enslaved people, including a three-year-old child named Titus. Additionally, he referenced George Berkeley — the namesake of the Berkeley Divinity School at Yale — who donated a farm worked on by enslaved labor to Yale, which funded the University’s first scholarships.

“Graduates of Yale College and then eventually of the Divinity School were largely participants in the owning of slaves,” said Kenneth Minkema, Executive Editor of the Jonathan Edwards Center and professor at the Divinity School. “So people like Edwards … were definitely a part of this network and they defended the institution of slavery as a biblical institution.”

Minkema, who leads research on the Divinity School’s history, and now is a member of the Yale and Slavery Working Group, also spoke about the strong presence of colonizationists — those who believed that after slavery Black people should be sent back to Africa — at the Divinity School in the 1800s. According to Minkema, Yale was a center of the colonization movement.

Martin, who served on the anti-racism task force, said that it is “awkward” to call the Divinity School’s ties to racism “the past.” He and Collins said that racism is still a present force on campus, and is still something students of color are faced with today.

“It seems like we have these lofty goals for the future, but we haven’t really sat with the ways that racism is very much alive,” Martin said.

Professor Nasrallah said she aims to bring “active critique and concern” to her work, especially as she and her fellow members in the diversity, equity and inclusion efforts think more about what underrepresented students and faculty need. It is critical, she said, to be open to transformation.

Nasrallah also said that it was important for her to make sure that this work continues, and that the task force’s recommendations are implemented, even after the dispersion of the task force. This is where the long-standing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging committee comes in, which, made of task force members and others, will be the next step for implementation.

“The Task Force was appointed for a specific charge and for a limited period of time. The DEIB committee is a standing committee that is charged with monitoring our progress towards the plan that we have formulated,” Sullivan-Harmon wrote. “Our collective commitment to the implementation and careful assessment of our recommendations, remains our highest priority.”

Collins told the News that it is his “hope” and “prayer” that the Divinity School will stay true to its commitments, and that one day those who are Black and Brown can feel that they belong and are supported in the walls of the Divinity School, something Collins was not always able to feel.

“My hope for anyone coming to YDS, or any school at Yale University, if they are Black or they’re a person of color, is to know that even though the environment, the world, the broader community may not agree with their blackness, even though the histories of the University testifies to the fact that they don’t belong,” Collins said. “My prayers are … that they will know that their leaders at least stand with them and believe in them and support them.”

The Divinity School announced earlier this month that it will cover the tuition cost for all students with demonstrated financial need.