Campaign continues work to remove SROs from schools

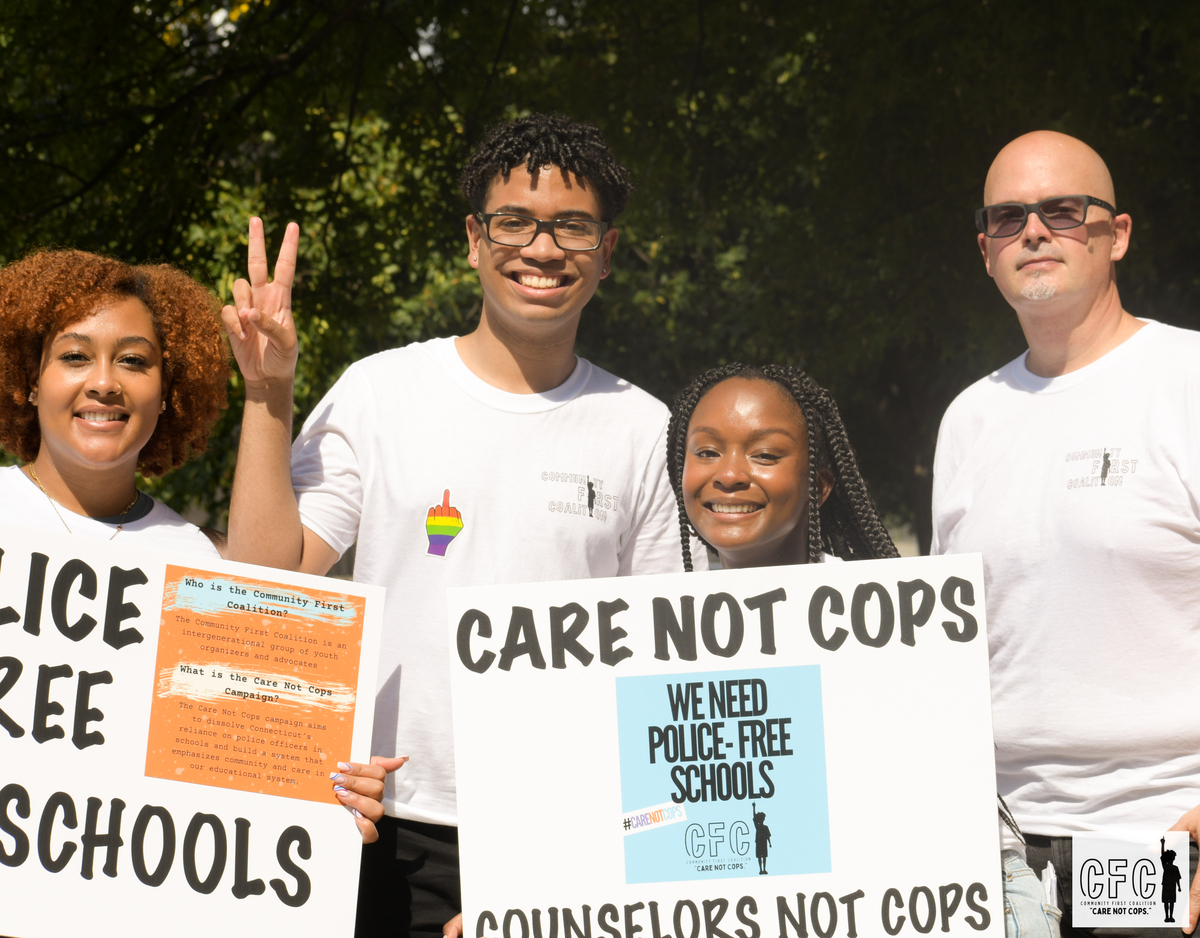

The Community First Coalition launched its “Care Not Cops” campaign last month, continuing longstanding efforts to remove SROs from public schools.

Sarah Cook, Contributing Photographer

A coalition of Connecticut youth-led organizations has recently launched a campaign to remove police from public schools and to change the nature of disciplinary actions, adding momentum to a movement that began during summer 2020 protests.

The Community First Coalition of Connecticut, a group of grassroots and youth-led organizations, was started 14 months ago. “Care Not Cops” — the coalition’s first campaign which was launched at a Sept. 18 press conference in Hartford — centers on removing police from public schools in Connecticut. Its main goal is to replace school resource officers, SROs, with school resource counselors, SRCs. It also aims to expand the definition of SROs to encompass security officers and non-police actors, advocate for transparency legislation for police-led interactions in schools and decriminalize chronic absenteeism.

“Why do we need officers with a badge policing our students, saying that our students are bad and posted around the school,” said Micheala Barratt, a youth organizer for Radical Advocates for Cross-Cultural Education. “It doesn’t make you feel like the environment is welcoming.”

SROs in New Haven

In January, the New Haven Public Schools School Security and Design Committee gave the New Haven Police Department recommendations that include increased funding for psychologists, the prohibition of police car parking outside of schools and better definition of the roles of SROs.

In April, the Board of Education voted to pass recommendations from this committee, but they did not vote to remove SROs. However, by passing these recommendations, the board was beginning its plan to phase out SROs from schools in New Haven.

Currently, there are five SROs in NHPS. According to Jahnice Cajigas, director of organizing for the Citywide Youth Coalition, the number of SROs decreased from nine to three last year due to budget cuts. Gary Hammill, police sergeant at the NHPD, told the News that two more SROs were added at the beginning of this school year.

These changes in New Haven came after CWYC-led protests in the summer of 2020 made eight demands, including replacing all SROs with counselors. Cajigas told the News that the group led protests by City Hall every Friday last summer. She added that Lihame Arouna, a CWYC activist and student board member, proposed the creation of the New Haven School Security Task Force — which decided on a phase out plan for SROs and worked under the governance committee.

Cajias said the culture of punitive practices remains no matter if SROs are removed because schools across the state and in New Haven still have security officers present at schools that check bags, deal with disruptive students and use metal detectors. SROs, in contrast, are mostly responsible for court referrals, according to Cajigas.

Charles Tyson, an SRO in New Haven, said that SROs do not enforce any disciplinary rules other than breach of security or serious juvenile offenses such as carrying dangerous weapons or “any egregious act that jeopardizes the faculty and student body.”

Tyson also told the News there is no formal training for SROs in addition to their police training. After they are selected as SROs, they attend a weeklong introductory class which covers safety protocols, emergency safety measures and how to create a safe environment with faculty and students. He also said they attend workshops and seminars when possible, and their training “constantly evolves to accommodate current social trends.”

“We are and have always operated in the schools with a community-based policing philosophy,” Tyson said. “We are fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters and police the schools with the mindset that the students and faculty are an extension of our family.”

Impact of Policing on Black and Latinx students

The Community First Coalition focuses on how policing in schools disproportionately impacts Black and Latinx students and contributes to the school-to-prison pipeline. In Connecticut, there are large differences in policing between schools with predominantly white students and schools with higher populations of Black and Latinx students, according to Iliana Pujols, policy director at the CT Justice Alliance.

Lauren Ruth, policy director at Connecticut Voices for Children, told the News that the risk of dying at the hands of a police officer is 3.6 times greater for Black residents then White residents in the U.S., according to 2019 data.

“Our public safety enforcement system has a twofold problem of being deeply rooted in American racism and structured using human intuition rather than empirically-supported best practice,” Ruth wrote in an email to the News. “While many — if not most — police forces have updated their training methods and engage in anti-bias training, these systemic issues are proving to be deeper than what an updated curriculum can solve.”

Pujols said that the presence of police can be traumatizing for many Black and Latinx students who may have prior negative experiences with the police.

Additionally, the prevalence of police brutality in recent years could lead to increased problems with the current policing in schools, according to Barratt.

Cajigas attended high school in New Haven and remembered seeing SROs in school after the murder of Trayvon Martin.

“I remember seeing the murder of Trayvon Martin, and then having to come to school or like just feeling that frustration and not feeling safe coming into the school building because there was police officers and even school security officers within and within the building,” Cajigas said. “ I think it’s a constant re-traumatization that we’re putting our students through, especially our Black and Brown students.”

Vision of the Coalition and Roadblocks

The coalition’s main vision is to reimagine the treatment of chronically absent students or students with other disciplinary issues. Instead of calling the police, Barratt said that a counselor should have a conversation with that student to understand the background of the situation. Pujols told the News that these counselors should also be credible messengers or people who closely resemble the school’s population to ensure students feel comfortable talking with them.

Tyson told the News that although guidance counselors and social workers are present in New Haven Schools, SROs are sometimes asked to step in to mentor kids “that can benefit from a positive role model.” He also told the News that BOE has a team of Truancy Officers that monitor attendance.

According to Barratt, it should not be a teacher’s responsibility to de-escalate situations or talk with students about potential reasons for their behavior. Instead, unconscious bias training for teachers should be implemented, she said.

“We have a host of anxious children who learn differently now,” Stubbs said. “Instead of having counselors there to help people work through their anxiety or work through their different learning styles, they have police officers there forcibly making them sit in school.”

According to the Connecticut Judicial Branch, three New Haven students were referred to court by SROs between Sept. 2020 and June 2021.

Ruth also told the News that one of the major roadblocks to removing SROs is people’s resistance to recognize the harm done by police officers based on their own positive experiences.

Jennifer Hudson, external affairs director at Connecticut Voices for Children, feels the desire of parents to keep SROs is especially strong in Connecticut because of the history of school shootings, but said that police officers are often the ones making students feel unsafe.

There are 44 New Haven Public Schools in the district.

Correction, Oct. 12 The article has been updated to reflect name changes in “CT Juvenile Justice Alliance” to “CT Justice Alliance” and Ruth’s first name — which is Lauren.

Correction, Oct. 13 The article has been updated to reflect the actual data from the Connecticut Judicial Branch — that three Elm City students, not 152, were referred to court by SROs last school year.