Malia Kuo

The bitches lived in the shed — a dilapidated, yellowing structure in Flora Hopewell’s backyard, by the pool. Probably, it was meant for storing shovels and birdseed and rusty wheelbarrows, but Flora’s parents weren’t the type of people to own objects for upkeep, so instead they kept dogs: A reality that my mother found appalling, and I amazing. When I remember Flora’s backyard now, sounds of whimpering and growling carry clearly over algae-infested pool water, unfettered by chlorine and skimming nets.

The first time I entered into the dogs’ shed, I was 9, maybe 10, wearing a pair of pink cowboy boots with spurs on the side and soccer shorts and a red sweatshirt from the Gap. I had dressed myself. It was a warm day in early December, the day of our first sleepover — Flora and me.

Flora, at the time, was the most popular girl in my class, despite her unibrow and the fact that she was new — her family had just moved to Charlotte from Orlando. She was very loud and very funny and a very confident dancer, though not a particularly good one. I was a very good dancer, though not a particularly confident one. Flora was one of seven siblings and lived in a big yellow house with blue shutters in the third fanciest neighborhood in Charlotte — the neighborhood where my mother wanted to live. Her father was a businessman. Her mother was a dog breeder. Everyone in her family was Catholic.

We became friends after being seated next to each other on a field trip to the Asheville Zoo. It was a two-hour drive and we chatted the whole way — about what, I couldn’t tell you. We were at the age when girls’ friendships are confounding for their sheer simplicity. She was very silly and I was very serious, or at least I presented as much. She was determined to prove me otherwise. Or maybe not. Sometimes I think I give her more credit for transforming me than I should.

Flora was the one to lead me to the shed, sprinting ahead in her blackened bare feet, leaving me to stumble after her with her younger sister. At that time, Flora still found the dogs thrilling, before the years of vomit and piss on her bed linen turned her against animals for good.

Babies! Flora cooed, swinging open the door, unleashing the red-orange glow from the heater lamps so that it poured out onto her shins, illuminating a thick hairiness that shocked me then. By the time I reached the threshold of the shed, she had already submerged and re-emerged, a near-fetal puppy squirming in her palms. It looked repulsive, but I knew I was supposed to find it adorable. I tried cooing, too.

With a finger to her lip, Flora shushed me.

“They’re sensitive now,” she said. “Keep your voice soft.”

Then, she turned to her little sister, whose halo of brown frizzy-curly hair burned orange in the glow of the shed’s lights.

“Go back to your room. This is my sleepover!” Her voice was loud. Already, she had forgotten her own rules.

Her sister frowned, tears welling in the corners of her eyes, and scurried away. I entered the shed with a strained smile.

Inside, warmth radiated. The ground was covered in dog shit and blood — a Hades for puppies.

“Why are the moms bleeding?” I asked, petrified.

“It’s very hot in here,” Flora said. “They bleed from the heat.”

I nodded, beginning to wriggle out of my sweatshirt as I stared at the groaning, swollen dogs and their hairless children.

“They look like soggy noodles,” Flora said, staring at me, staring at the puppies.

I nodded. She laughed.

“Want to hold one?” Flora asked me.

I wasn’t comfortable around dogs at the age of 9. I wasn’t comfortable around any animals, really. At my house, there were no pets — too dirty and too loud and most of all too expensive. I didn’t mind. Their sharp teeth and clawed paws made me skittish.

“Yeah,” I said and looked at Flora, forgetting to smile this time.

One of the dogs was buried beneath the rest, all of them wriggling over one another, struggling to latch hold of their mother’s teat. Flora slipped her small hand through the mass of naked puppy bodies, and grabbed the smallest body between her pink-polished, chipped fingertips.

“The runt,” she said to me, grinning. “Usually, my mother says not to hold the runt. But it’s so cute! Isn’t it?”

I convinced myself that it was.

“And, also, sometimes, I feel bad for it. It’s soooo tiny,” she said, scrunching up her nose. I nodded and mirrored her, scrunching mine up too.

“Hold it!” Flora said, dumping the puppy’s small, pallid body into my hands. It was warm and wet, probably from the excess milk and piss that its brothers and sisters leaked.

“What kind is it?” I asked Flora, whispering, trying hard not to wake it.

“A dog!” She said, erupting in laughter.

“No,” I said to her, blushing, my voice dropping so soft that it was closer to silence than sound. “I mean, what kind of dog?”

“A King Charles Cavalier,” Flora said proudly.

This meant nothing to me but sounded magnificent. I nodded.

“And by the way, it’s called a breed.”

“What’s her name?”

Flora yanked the runt from my hands, flipped it over into her palm, and inspected its genitals.

“What are you—”

“Oh,” Flora said. “You’re right. It is a she.”

“What’s her name, though?” I repeated.

“These dogs are nameless. Each one is named Nobody. We sell them. My mom says they’re not ours to name.”

Again, I nodded. Dogs for sale. Named Nobody.

For the next hour we sat in silence, stroking the bodies of all the babies, trying not to disturb the mothers, adjusting to the stench of shit and puppy breath until it smelled to us like fresh air. I was at once petrified and proud of the presence of so much life younger than myself in one enclosed place. It felt like I imagined babysitting would feel one day. Maybe even better. I nestled a puppy on my knee, another on the crook of my crotch, and more and more climbed atop me. The minute heaviness of each body pressed into my skin, sunk into my muscle, and I let myself warm to them. The spots where the puppies laid went tingly, but not the kind of tingly of a sleeping limb — the opposite, something much more awake. I closed my eyes and smiled. And then I remembered my cowboy boots, their heaviness and pointiness and side-spurs, which glinted in the heat lamp’s orange glow. I didn’t want to crush one of the puppies, and I didn’t want to spur a puppy either. But I had the acute feeling that if the puppy ran into my spur, or wriggled itself beneath the sole of my boot, then that would be a cosmically justified fate. And this knowing scared me deeply.

“I am going to have as many babies as a dog has in a litter,” Flora announced, interrupting my trance.

“How many babies is that?”

“Eight, but one will die, probably. Just like my mom’s eighth baby.”

“One will die?”

“There’s always a runt that dies,” Flora said. “Seven is a holier number, anyway.”

I nodded, unsure of what she meant.

“Seven babies is a bunch,” I said, to say something.

“No, four is a bunch,” she shot back.

Flora kept petting the dogs. I kept quiet.

Eventually, both she and I began sweating, droplets forming on our foreheads like liquid kibble.

“I’m hot,” she announced finally. “Let’s go.”

So we did, unearthing ourselves from the bodies of the puppies, and rising once again to our feet. I wiggled my toes in my boots.

“Your cheeks are so rosy,” Flora said.

I touched them, feeling the hot pink flush. I don’t think the flush was so much from the heat and dogs and the humidity of the shed, as from a related but estranged thing. A thing hunkered in the gutters of my own body.

Flora grabbed my hand and yanked me out of the shed.

“Gooooodnight!” She sang to the dogs, locking the door with the bolt, forgoing my hand for the door’s metal.

“Goodnight,” I whispered, too. The 30-degree Carolina December air cut the ties from my body to the dogs. I watched my hot breath turn to clouds, then turned to the pool to breathe its air.

“It smells funny out here,” I said, sniff-sniff-sniffing.

“It smells funny in there!” Flora said. “You just forgot.”

She grabbed my hand again and pulled me around the weed-ridden pool, through the weed-ridden garden, to the back door of the yellow house, then toward her bedroom. There, the carpet was soft, and the walls white, and her bed a humongous boat-like mechanism, with a headboard that read “Flora” in painted pink cursive letters across the middle. Besides the bed, not much furniture populated the space, save a night table and a bean bag chair in the corner. There were no dolls and there were no animals, only traces of fur and her own dead hair strewn about the white carpet and bed sheets. The light to her closet was switched on, white-yellowness creeping from beneath the door. It reminded me enough of my own bedroom. I sighed, shut my eyes, opened them again. Relief.

“I like your room,” I said. “What now?”

“Let’s shower. You’re so stinky!”

“Hey… you too!”

I followed Flora into her bathroom, where the tile was white and black, and we both stripped down to our undies.

Hers were blue, striped, tattered by the elastic. Mine were pink, they said Friday on the front. Humiliatingly, my mother still picked out my underwear to correlate with the day of the week. I knew I was too old for that, and damned myself for forgetting to change.

Flora pulled back her floral shower curtain and turned on the tap. “Tadaaaaa!” She sang, then stripped down.

I stared at her, then slowly slipped off my own underwear, slinking them down my skinny thighs. Though I had a few sleepovers before, none with such little adult supervision. I followed Flora’s lead blindly, desperately.

She hopped into the tub and stretched the length of her body out, so that her toes sunk under the tap and her shoulders laid flat against the floor of the plexiglass shower-tub.

For too long, I looked at her glistening body, at its hairiness and its length. Flora was shorter than I, by five inches probably, with brownish skin and blonde hair with dark roots. It was never dyed — it must not have been — we were too young for that, surely. But it looked like it could have been bleached. Her unibrow knit her round face together, shadowing the bow of her plump lips. I shivered, desiring to be under the flow of the warm water with her.

“Come in!” She motioned for me to join her.

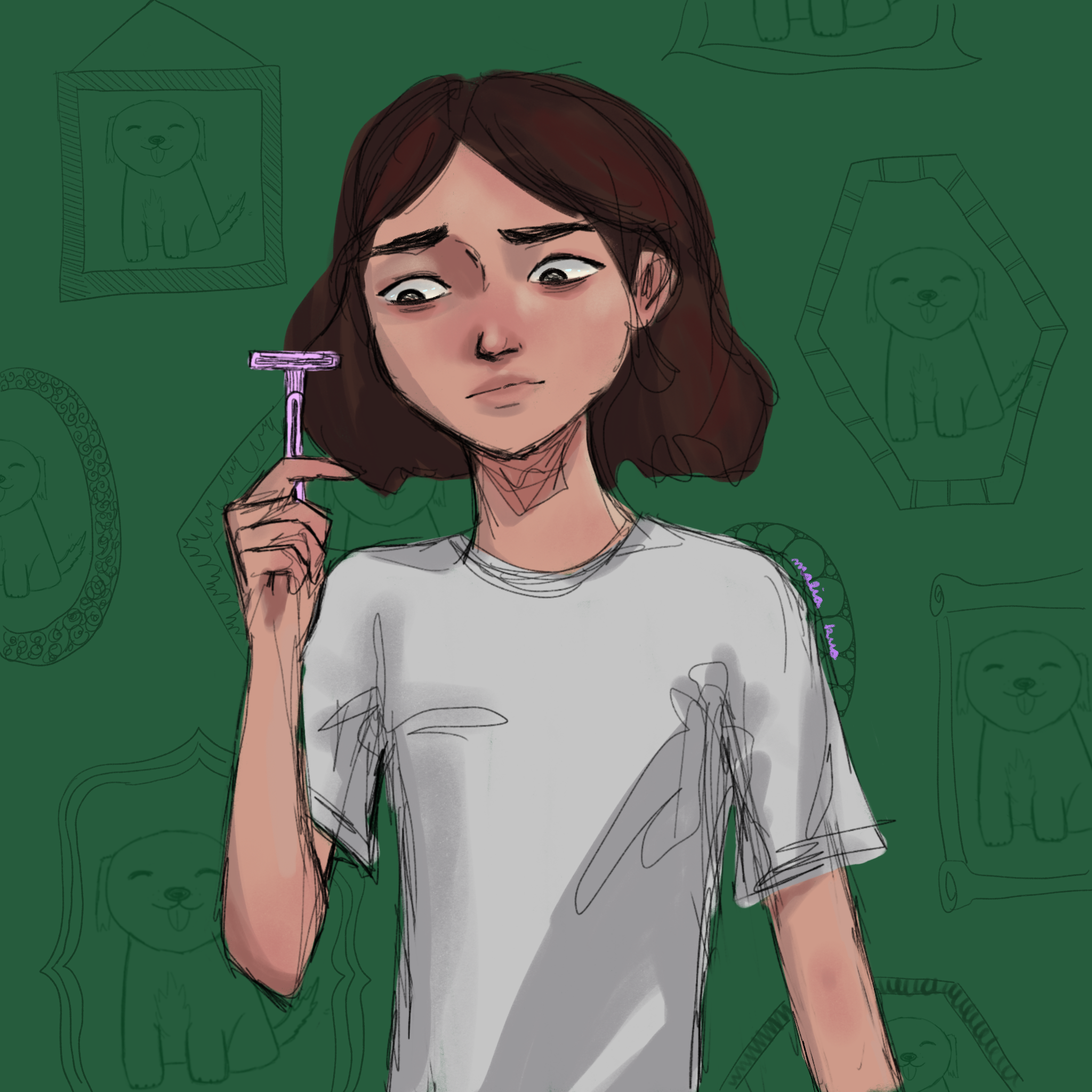

On the edges of the tub, there laid half-empty shampoo bottles, and bubble bath, and toy boats, and pink soaps. By the faucet, there was a purple razor, belonging to one of Flora’s older sisters, surely.

“Sit down!” Flora said. Though my toes were in the tub, I was still standing, looking down at her body, which was now fully submerged. I watched the water inch closer to her nose, to her mouth, then sat down. I squeezed my back between the faucet and the wall and pressed my legs together. From there, I could see her vagina well. I closed my eyes, took a breath.

“I see that you have pubicle hairs,” Flora announced.

“I have what?”

“Pubicle hairs. They are hairs of adults,” she repeated.

I ran a finger through the mousy, brown-black locks that ran from my head down my back. She erupted into a giggle-fit again.

“Pubicle hair is the hair around your BODY,” she said. “And when I say BODY, I mean your private parts.”

I peered my head down to my vagina. Obviously, I had already noticed the hair there.

You don’t have to be embarrassed. It just means you’re growing.

I crossed my legs, pressing them tightly together.

“Then where is your hair?” I asked.

“It’s coming along,” Flora said. “I am just not as mature as you yet.”

She pronounced the “t” in mature like it is in titillating, instead of using the “ch” sound like my mother did.

“It’s nothing to be embarrassed of,” she said again. “It’s just like, you are the puppies when they are 6 months old, when they begin to get their grown-up coat. I am the puppies when they are, like, 6 weeks old.”

“But we are the same age.”

“No, you’re January. I’m March.”

She switched off the faucet. I leaned my shoulders deeper into its warmth. I could see her naked body, with all its lumps and flaps, perfectly. I didn’t close my eyes.

“You could shave it, you know,” Flora said to me then.

“Shave what?”

“Your pubicle hair, duh.”

I must have given her a petrified look — she rolled her eyes at me.

“My sister does it all the time. She’s 15.”

“But I’m only nine!” I said. “Shaving is for teenagers.”

“It’s not a big deal,” Flora grinned. “It won’t hurt, and then we will be matching! We’ll have matching bodies, like we’re from the same litter.”

I shuddered again, though it was too soon for the water to be cooling.

“Hand me the razor,” Flora demanded.

I turned my torso and grabbed its lavender rubber handle, inspecting the sharpness of the blade before placing it delicately in her hand, just as she had placed the puppy in mine.

“So basically, it’s simple,” she said to me. “You just put it on your skin, press down and pull back. But not too hard! Or else you’ll begin bleeding.”

She mimed the action on her own body, leaving space between the razor and her skin. I looked on, nodding.

“Do you want to do it to yourself? Or do you want me to do it?” She asked.

“I’ll do it,” I said, taking the razor back again, bringing it beneath the water’s surface toward my body.

The water obscured the hairs, but I could count about 10 there, all dark and all thick and all womanly. I looked at Flora, and she smiled at me, encouraging me to go on. I felt like crying.

“Wait!” Flora said. “Do you want suds?”

“Suds?”

“Like to suds up your skin before shaving.”

I faltered.

“They smell nice,” she said. “And my sister does it.”

I sudsed up my body with Mr. Bubbles, the cherry aroma pulsating through my nostrils, then put the razor to my skin and pulled back. Flora watched me, quiet for once.

After a long second, I pulled the razor up from beneath the water’s surface, inspecting the blade for hair and blood.

“Did you get any?”

“I see some hairs. But do you think they’re mine?”

“Whose else would they be?”

“Maybe your sister’s! Leftovers.”

“Oh.”

Flora plunged her head beneath the surface of the water and opened her eyes wide, then emerged again, gasping.

“My eyes burn, yikes!” she said. “I think you got them. But you better go again to be sure.”

I made another stroke with the razor blade. More hair appeared this time on the the metal grate.

“Got them!” I announced, beaming.

Flora drained the tub, tears streaming down her cheeks from the soap in her eyes. We hopped out.

“Good job,” she said. “Now shake your booty! We are both naked baby doggy-doo-doos!”

I emerged from the tub and began dancing, grabbing for Flora’s white towel on the hook and swaddling myself in between spins. We walked out of the bathroom without brushing our teeth, Flora dropping her towel by the threshold. I realized then the rust-red stain on my own towel. I looked down to see avenues of blood streaking my vagina. I had cut myself with the razor after all.

“I am sooooo sleepy,” Flora announced. “I never get this sleepy at sleepovers. Usually, I stay up until 5 a.m., super hyper. But I am sleepy now and I think I will sleep.”

She wriggled into her pajamas — a green polka-dotted cotton set.

I was humiliated by the blood oozing out of me, by the stain that I’d left on her towel. Surely, Flora would see it in the morning, and if she didn’t, then her sister or her mother would in the late afternoon in the laundry bin. I snuck back into the bathroom to put my dirty underwear on beneath the clean ones my mom had helped me pack in my overnight bag, hoping that it would keep the blood from bleeding through the cloth onto Flora’s sheets. I slipped my nightgown over my double-undies and slunk into bed. Flora’s breathing steadied beside me. The whole night, I remained rigid, desperate not to wake her, terrified that a bit of my insides might stain her pink sheets, revealing to her the true reaction of my body to our bath time.

In the morning, I woke to penetrative sunshine and the sound of Flora’s mother’s voice by her door frame. She’d made pancakes, she came to tell us.

Flora rolled over to my side of the bed, took my shoulders in her small hands and shook me.

“Pancakes! Let’s go,” she said, her hot puppy breath beating down on my lips.

I excused myself to the bathroom, and locked the door, and checked my underwear. The blood had dried, not even seeping through to the second layer. I put on my shorts and my boots for the day, and had breakfast with Flora’s family. Hours later, my mother picked me up. I was sad to go, but Flora promised to invite me back. And she did. For the following years, I spent as many Saturdays as I could at Flora’s house, playing with the dogs, helping them nurse, watching them mature and leave for new families. As we got older, the two of us spent incrementally more time away from the puppies and in her room, or by her pool instead. We bore our growing, hairless bodies to the sun and complained about the barks and stench of puppy shit that still festered, not far away, in the shed.