Nuno Monteiro, associate professor of political science, has died

Professor Nuno Monteiro died on May 5 from causes not yet disclosed. He is survived by his wife and two young children.

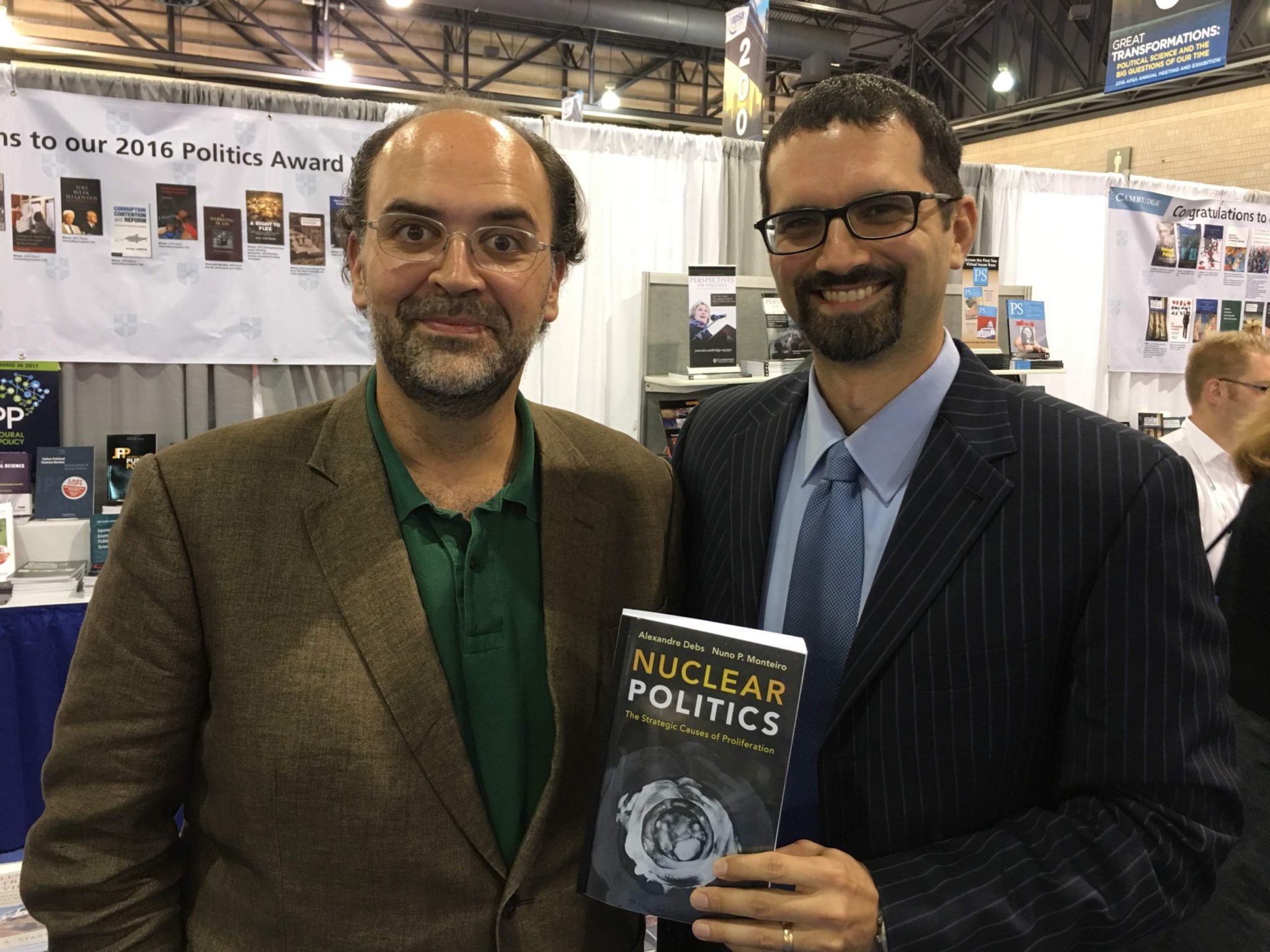

Monteiro (left) with Alexandre Debs. (Courtesy of Alexandre Debs)

Nuno Monteiro, associate professor of political science, died on May 5 from causes not yet public.

Monteiro, who received his B.A. from the University of Minho in 1997 and his doctorate in Political Science from the University of Chicago in 2009, most recently taught “Approaches to International Security,” one of the core courses in the global affairs major, and an international relations workshop. His research, within the fields of international relations and security studies, has led to two books, numerous articles in research publications ranging from the “Annual Review of Political Science to International Theory” and commentary in Foreign Affairs, the Guardian, and more. Monteiro was a research fellow at the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies and a fellow of Branford College. He had previously served as director of International Security Studies.

“Nuno was not just a towering intellectual figure in the field of international relations,” Stephen Herzog GRD ’21 wrote to the News. “He was also just a wonderful and fundamentally good person. As a scholar, teacher, mentor, and friend, I feel lucky to have gotten to know him and to have benefitted from his advice on everything from structural realism to Japanese post-war cinema, to whiskey selection. His students and the department will miss him terribly.”

Monteiro’s death caused an outpouring of grief from current and former advisees, professors, students and colleagues alike. Twelve of Monteiro’s colleagues, mentees and students, in interviews with the News, expressed their gratitude towards the “juggernaut” in the field of political science for his friendship and mentorship — and dismay that his life, both as an academic giant and as a husband with two young sons, was cut so short.

Elisabeth Siegel ’20 called Monteiro “the greatest professor that I had at Yale.” In an email to the News, she emphasized his accessibility to students, keeping an office hours link accessible to anyone, to talk about anything.

“I am in my current graduate program because of his guidance and mentorship, studying topics that, for the most part, he facilitated my interest in, or outright introduced me to,” Siegel wrote. “It would be no small understatement to say that he changed my life, probably to an extent that he was totally unaware of. He was extremely humble and all around a great person all around, especially in the way he treated others. He will be missed.”

Monteiro’s website, along with having a link to office hours on the bottom of pages, also consists of tabs listing his own advice for undergraduates, graduates, research assistants, coping with procrastination and more.

“So think of your college years from the perspective of your old age — say, 35. What will you regret more from that vantage point?” he wrote of taking advantage of one’s college years.

David Minchin GRD ’21, for whom Monteiro was his dissertation chair, Monteiro was both “effortlessly brilliant,” but also a stellar mentor, “as permanent a fixture at Yale as the buildings themselves.”

He had a great sense of humor, a winning smile and was genuinely invested in his advisees, Minchin added. But he was also an intellectual force.

“I was at APSA, the largest annual political science conference, and there was a roundtable on Nuno’s latest book, Theory of Unipolar Politics,” Minchin wrote. “I sat down and realized that the panel consisted of John Mearshiemer, Charles Glaser, Stephen Walt, and James Fearon. For those unfamiliar with the realist strain of international relations, this was essentially the equivalent of having the Beatles come together to discuss your new album.”

Alexandre Debs, associate professor of political science and a co-writer with Monteiro on “Nuclear Politics: The Strategic Causes of Proliferation” as well as several research articles, wrote to the News in an email that Monteiro was “efficient to the power of ten.”

During their pre-COVID-19 coffee breaks, Debs added, they would discuss everything from world history to European shoes.

“He had an uncanny sense of humor and made me laugh every day,” he wrote.

Gregory Huber, department chair of political science, called Nuno a “key figure” in international relations at Yale, and James Levinsohn, director of the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, said that he was an “integral member” of the Jackson community who “cared so deeply about his students and consistently went the extra mile.”

This care for students can be demonstrated from a December 2020 email correspondence between Angela Avonce-Malavet ’22 and Monteiro, after she finished his global affairs course and thanked him for the semester.

“Apologies for taking so long to reply,” Monteiro wrote back. “I wanted to write something meaningful in response to such a wonderful letter from you. The best I can say is that receiving messages like this is among my favorite aspects of being a professor. My deep thanks for taking the time to let me know how the course mattered to you. I am truly delighted to hear of the positive impact the course had on your intellectual growth. It’s the most a professor can aspire to achieve.”

Monteiro is survived by his wife and two young children.