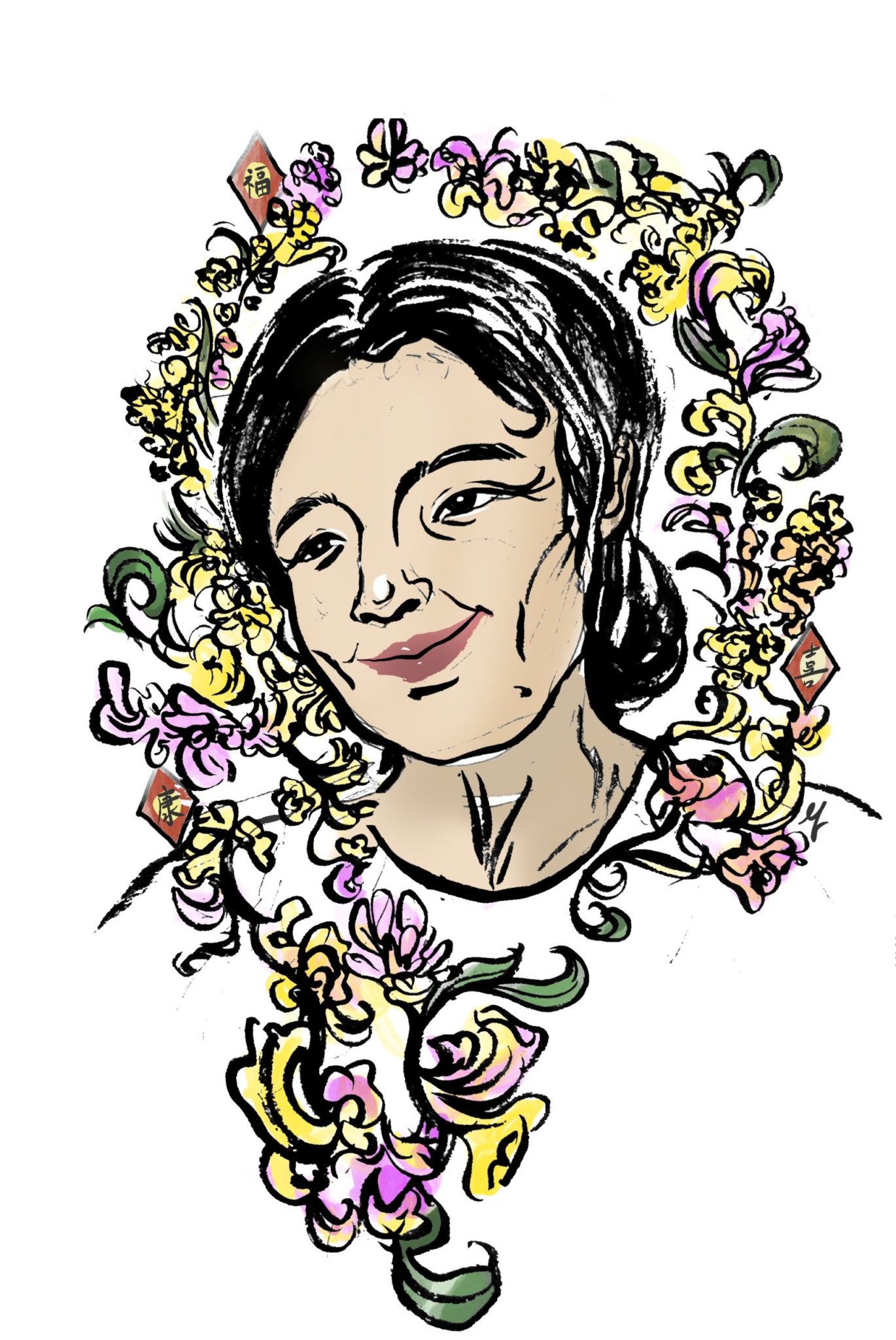

Ivory Fu

Bodies are beautiful like flowers, though unlike many flowers, they are not perennial. This simile may seem obvious. The greatest distinction between these two organisms, however, is that people consider all flowers beautiful, seldom abhorring a specific type. Some flowers may be more alluring than others, but each bears its own enchanting traits. The same cannot be applied to views of the human body: handfuls of people see those of other communities and find them unbearable. Bodies are beautiful like flowers, though some bodies loathe other bodies.

The Atlanta shooting proved this comparison correct. It was another bullet point on the extensive list of Asian American hate crimes this year — a list that goes on and on and on until it runs off of the page and onto new ones, highlighting the unsurprising fact that since the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, xenophobic and racist rhetoric and crimes against our community have not subsided. Asian Americans of all hues continue to be hurt, traumatized and murdered in the United States — our home.

As I hear and read news of this ongoing hostility, I recall the Lunar New Year, which many Asian Americans, including my family, celebrated this February. There are nuances to how each household celebrates, so I will speak for mine. My family adorned our Buddhist altar with an assortment of flowers and ancestral offerings in the form of Vietnamese dishes. The most noticeable decor was the hoa mai, or forsythia flowers, which created a jungle in our freezing Minnesota abode. We embellished this striking yellow plant with the typical scarlet and golden ornaments — colors that symbolize good luck and prosperity. I elaborate on all of this preparation because it instilled in us a sense of optimism: we cleaned our homes, endeavoring to rid them of bad luck, ensuring a positive, fresh year. 2021 is the Year of the Ox, an animal that symbolizes perseverance, and everyone has undoubtedly endured due to the pandemic, especially low-income and middle-class communities. After much economic hardship, this year was supposed to be better. We believed it.

A week ago, I watched “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” a movie about the legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday and her fight against racism as a Black woman with power. The U.S. government endeavored to ensure she didn’t sing “Strange Fruit,” a song about lynched Black bodies swinging from the trees. Federal agents feared that the song would spark growth in the Civil Rights Movement, making Black civil rights activists uncontrollable. Holiday, however, disobeyed and performed the protest song unapologetically in front of her audiences. I think of the Black bodies about which Holiday sang as I reflect on the hurt that Asian Americans are feeling, and have felt, since the first of our kind arrived to this land of seemingly unparalleled happiness. The red and golden Lunar New Year ornaments that dangle on branches of the forsythia represent each individual that has died because of hate, that has been traumatized by hate: from the elders who are shoved viciously onto the pavement and the spa workers who are murdered to every Asian American who encounters hate but has not reported it due to language barriers. In life, everything is a symbol — an unsettling, yet true, fact of this universe.

I’ve been trying to pinpoint what emotions swim inside of me. I’m confused. I ask myself if I am wrong for not crying because I just don’t know what’s going on anymore — I’m sure that many resonate with this sentiment. In Boulder, Colorado, 10 more people were just murdered. This country has issues, has had them since its inception. I discern leaders and public figures and citizens speaking out against the Asian American hate crimes, and they sob whilst taking action. They have to explain themselves to ignorant state representatives, like one in Texas. Asian Americans have reconciled mourning and mending.

Ultimately, there is no one right way to cope. For me, I write and eat ice cream and cuddle with my puppy, Kenzie. I’ve been trying to prioritize myself as well: that assignment can wait one or two more hours — I need, we need, both time and space to breathe. And I know that we must love, must love, must love. And I know it’s hard because we desire to hate first because it was this same emotion that ignited everything evil. We must love first ourselves and those nearby, then, like a forsythia, branch out. We love because bodies are unlike perennial flowers. Perennials may perish in winter and rise in spring and repeat this cycle for years upon years, upon years, upon years, upon years, but bodies are not as blessed. They each experience a single death and then become a red and golden ornament on the forsythia — a strange, swinging fruit. Bodies die once. And then they are gone.

John Nguyen | john.nguyen@yale.edu