Cassidy Arrington

Even after 15 years as an archivist, Michael Lotstein still gets a thrill when he works with primary source material, which he calls the “tangible aspect of historical inquiry.”

“Sitting at a table with documents that were written three, four or five hundred years ago, and just being able to touch it and see it and handle it is very intoxicating,” Lotstein, the University archivist at Yale, said.

Lotstein had never planned for a career as an archivist. He attended Arizona State University, of which he is evidently very proud — during the interview, he wore a maroon ASU T-shirt and flashed the “fork ’em devils” hand sign while describing his academic trajectory. But after completing his master’s degree in history there and working in the government documents division of ASU’s library, he was unsure where he wanted to take his career next. Working in an archive was “something I hadn’t really thought about before,” Lotstein said. “Once I looked into it, it just kind of clicked for me.”

Lotstein exudes a calm, kind demeanor, often beginning his answers with the phrase, “That’s a great question.” He joined the Zoom interview from the converted work space he and his wife both use in his home in Hamden. He is flanked by large windows, a tall bookcase and a fireplace topped with picture frames. Lotstein has worked at Yale since 2011, and initially arrived at the University as a processing archivist, handling already appraised material, summarizing its contents and preserving them appropriately. In 2015, he assumed his current position as the University archivist.

In this role, he collects ephemera that relate to Yale’s history as a university, including letters written by a head of college’s wife to students fighting in World War II, the original charter founding the University in 1701 and all kinds of student work. These documents contribute to the archive’s almost nine miles’ worth of physical records and over 20 terabytes of digital records.

Currently being added to the University collection is Lotstein’s newest archive: the Help Us Make History project. This archive is an ongoing attempt to document Yale students’ experiences living and studying through the COVID-19 pandemic. This project is one of the University Archive’s 1,175 individual collections, and it’s the only one Lotstein is actively collecting for. Although Lotstein is no stranger to archiving the present moment — in 2019, he worked to preserve the 50th celebration of Yale’s coeducation — the project is unique because of the speed with which the archive had to adjust to working remotely and the rush to document student experiences during the pandemic. Realizing that the pandemic, and Yale’s subsequent closure in the spring, was an important historical event, Lotstein and his boss Christine Weideman sent out a survey in March in coordination with the Yale College Dean’s Office to document students’ reactions to the move off campus and to online learning. The survey asked open-ended questions about their experiences learning remotely, their feelings and concerns for the future. When the survey was more successful than Lotstein imagined, receiving over 200 responses, he realized that students were eager to share.

“There’s a market for preserving and documenting the events that … were going to be unfolding in the future,” Lotstein said. “Help Us Make History was really a way for us to regularly communicate with students through the prompts that we’re putting together.”

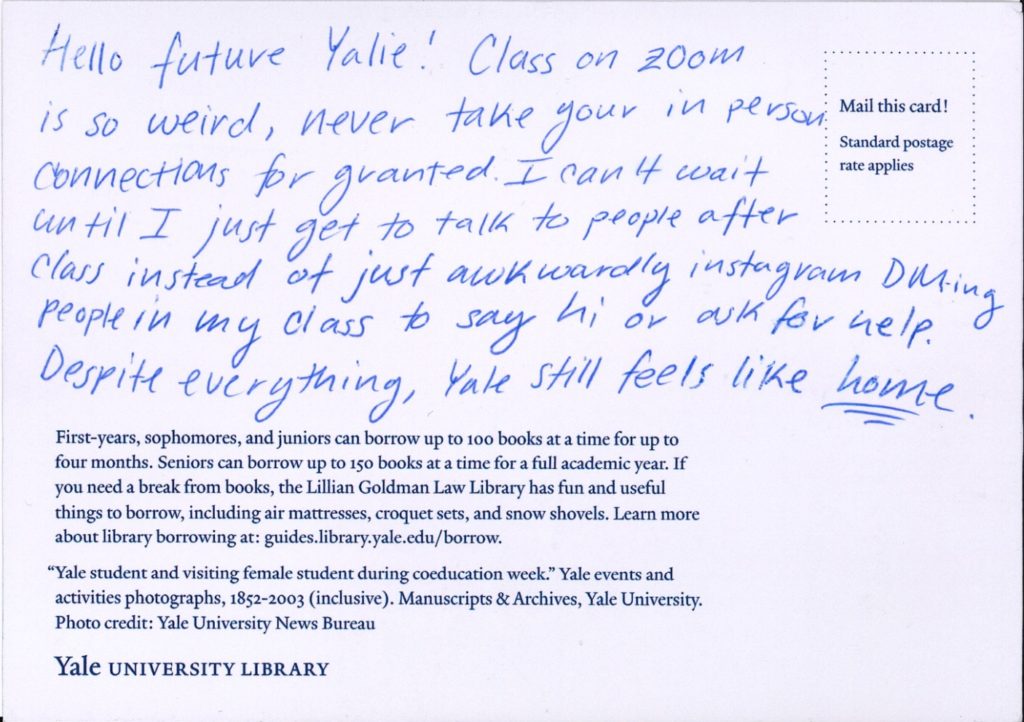

The questions sent in the first survey sought to gather students’ experiences of and immediate reactions to the changes induced by the coronavirus. The project’s website, which remains open for submissions, primarily features self-reflective prompts. It asks what students’ biggest accomplishment was during the fall semester, how they maintained connections during the pandemic and what they want future students to know about being a Yale student in 2020. In addition, on Oct. 14, students were invited to write postcards in front of Sterling Library that answered the prompt “What would you like future students to know about being a Yale student in 2020?” to be included in the archive.

Since the project’s inception on April 16, 2020, Lotstein has compiled 315 online submissions and 206 postcards giving insight into the lives of Yale students during the pandemic.

In the responses, many students stressed the negative impact that the pandemic has had on their mental health and the struggles they have had with online learning. “Online classes suck. I don’t learn well online. I don’t feel like a real student anymore. This is not the education I was promised. All my professors are doing their best, but it’s so hard to motivate students virtually,” one student wrote.

Many shared that they miss their friends from Yale and being on campus. Others wrote about their concerns for family member’s health and fears of financial insecurity. “I’m without heat, internet and stable health insurance to treat my worsening mental and physical health,” one student wrote.

In addition to relating their struggles, some also wrote about silver linings. “The experience of living completely within the confines of my neighborhood block has been revelatory of a sense of place which we have lost. Every day, I go for a walk with my mother, and she points to every house, wall, tree or corner and tells a story rich with experience and meaning intimately tied to this previously lifeless space,” one student mused.

Another shared a lighthearted takeaway: “I have mastered the art of creating a Zoom space in my bedroom that makes it appear as though my room is clean and orderly, when in reality, it looks like a bomb has gone off. Faking it till you make it, right?”

In creating the project, Lotstein wanted to give students the opportunity to share their stories in whatever way they saw fit. All submissions are encouraged to be anonymous, a practice which Lotstein believes has fostered participants’ “no-holds-barred responses.” Lotstein said that anonymity also protects responses from affecting the future careers of any Yale students. Also, the prompts’ open-ended nature allowed students to share freely at whatever depth they preferred, even if it was just a few words or sentences. He believes that there is value in all kinds of contributions. “All of it collectively builds the historical record of the University during the pandemic and your contribution is important,” he said. They plan to continue collecting responses through the website for the foreseeable future.

“In large part, the history of the University is written by the students during their time here at Yale,” he said. To him, archiving the experience of Yale students during COVID-19 holds significant value both for the present moment and the future. He believes the project creates a space for students to share their experiences and participate in the creation of the historical record, in addition to raising awareness of the role of the University Archive at Yale.

ARCHIVING EFFORTS

The pandemic has complicated Lotstein’s ability to do his job. The archive now has a strict schedule that limits the number of people allowed in any day. Lotstein currently works from his home in Hamden roughly half of the week processing digital records, and spends the other half on campus fulfilling requests for access to archival records.

“The biggest challenge for me is just making sure that students are getting access to what they needed in a timely manner,” Lotstein said. “I think that’s something that my whole department has been struggling with because so much of our digitization efforts are reliant upon student work that no longer exists.”

While the archive gets the same amount of requests for records, Lotstein isn’t able to get students what they need as quickly due to restrictions on how many staff can work in person at a time. “Our volume has stayed the same, but our staffing has plummeted,” Lotstein shared. “We’ve all had to pitch in.” Lotstein sometimes goes in extra days throughout the week to scan documents for students who need archival information.

Despite these everyday challenges, Lotstein sees the work as critical. The archives present a crucial, though often overlooked, connection between the past, present and future. “The value of archiving is that without it, there’s no historical record,” Lotstein said. “Things will just vanish without somebody out there preserving them.”

At the same time, archivists must be attentive to current events and have enough foresight to know what will be important to preserve for the future. “There’s a trend towards archivists as activists, meaning that there is a recognition of the importance of events as they’re happening in real time, whether it’s Black Lives Matter, whether it’s social justice movements, whether it’s going back a few years to Occupy Wall Street or when you live in a community that just suffered a mass shooting,” Lotstein said. “The records that are being created through interviews with survivors or interviews with people on the ground protesting or documentation being produced through artistic expression or journalistic inquiry. The records that … come out of all of these active events need to be collected.”

Michelle Peralta and other archivists with Yale Manuscripts and Archives are working on a project called Hindsight 2020, which aims to paint a picture of the lived experiences of the greater New Haven community through online submissions. Lotstein’s project, and its prompts, focus primarily on Yale students, with one prompt open for contributions from Yale faculty and staff as well.

“Archivists need to be conscious of the fact that the … historical record is going to be built on these events,” Lotstein said. “It’s important that archivists maintain connections with groups and organizations in their communities … to make sure that these records are being [kept].”

While the Yale archive has actively collected student experiences since the University’s founding, Lotstein believed that collecting practices have ebbed and flowed over the years.

“When I took over in 2015, one of the things that I noticed pretty much immediately [is] that there had been significant under-collecting of records documenting student life on campus,” Lotstein said. “I’ve really tried to make my focus around collecting the records of student organizations.” Lotstein argued that archiving student work and records from other student organizations as part of the University Archive is worthwhile. Yet Lotstein noted that most organizations were surprised that the archives wanted to record the student experiences on campus; evidently, most people aren’t used to thinking of posterity or their place in history as they go about their lives at Yale. Lotstein was pleased to enlighten them here: Archiving their work and events “demonstrates the value of who they are, what they do and the records they produce,” he shared.

Unexpected support for the Help Us Make History project came about through a collaboration with a group of Saybrugians — Henry Jacob ’21, Micah Young ’21 and Adam Haliburton ’10 GRD ’21 — who developed a podcast called “Say and Seal.” The podcast, which has released two episodes so far, features interviews with students about leaves of absences. Future episodes plan to cover public health and politics.

Early in the process, a mutual friend suggested that they reach out to Lotstein. When they did, the University archivist was enthusiastic about the prospect of helping support their podcast and including it in the official archive, especially because he shared a connection to Saybrook — Lotstein has been a Saybrook Fellow since 2012.

As this is Lotstein’s first time supporting production for a podcast, he has welcomed the “fantastic, serendipitous experience” to learn more about podcast creation. Although “98 percent of the work was the three of them,” Lotstein said he has “pitched in … University resources when they needed it.”

The inclusion of the podcast as an audio component to the primarily written COVID-19 archive has benefited the project.

Haliburton feels that “an official history can always be made more illuminating, more filled-out, with contemporaneous voices.”

Jacob considers the podcast to be a “small-scale project” for the Yale community. “If one student in 50 years listens to an episode and uses it for a class, or even finds it interesting, I think our job is done,” he said.

LOOKING FORWARD

In processing the submissions to the Help Us Make History project, Lotstein has been struck by “the extraordinary way that they’ve been able to communicate their feelings and their opinions.” Lotstein said the submissions have been “so cogent and so eloquent in such a small amount of text or within the context of a photograph or a video or the podcasts.”

Lotstein acknowledged that it’s hard to know how the archive will be used in the future, but said he anticipates the perspectives contained in the archive being valuable for future researchers, students and professors. By collecting a wide variety of information and opinions in the project, future researchers will be better equipped to understand student experiences during the pandemic. Lotstein also speculates that if online learning becomes a larger part of Yale in the future due to the shift online that began with the pandemic, the project will play a large role in preserving the reflections of students living through the change.

Lotstein hopes that on an emotional level, preserving the Help Us Make History project for the future will “allow people to step out of the experience and give them a chance to heal, mentally, physically, emotionally.” And for some, revisiting the archive later on “may bring up a lot of feelings” or help them “find some sense of closure,” he said.

In collecting and preserving the experiences and memories of students during the pandemic, he hopes that current and future students will find the record useful. “My hope would be that this project helps … bring everyone together under that common cause of perseverance through the pandemic.”

Credit: Michael Lotstein