Dora Guo

As residents of New Haven, we are situated in the midst of two communities with dramatically distinct life expectancy rates and educational outcomes. While Prospect Hill and the downtown area are less than two miles apart, remnants of 1930s redlining and zoning laws have caused its residents to pay the price of socioeconomic and racial segregation — inequitable access to resources as well as an imbalance in school performance between integrated and segregated neighborhoods.

Desegregate CT, an organization founded by Sara Bronin LAW ’06 in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests this past June, aims to correct decades of discriminatory housing policy through a series of statewide zoning reforms in Connecticut, one of the most segregated states in the nation along both income and racial lines. Volunteers and nonprofits collaborate to do research, advocate and educate on how to make a more equitable Connecticut.

This coalition of “neighbors and nonprofits” argues that land laws hurt not only the most socioeconomically vulnerable in the state, but also all residents; thus, pushing for zoning law reform will result in just communities, a thriving economy and a cleaner environment. Desegregate CT focuses on zoning reform to create more housing throughout the state, reduce the overall cost of homes and build a more diverse housing stock. Currently, one in six Connecticut families pay 50 percent of their income on housing and the state’s population is declining, yet its land use laws are hindering racially and economically diverse populations. A large portion of the state’s land is zoned for single, standalone houses, which are expensive and contribute to sprawl, creating a divide between affluent and low-income neighborhoods and in some cases, towns that are geographically close to one another but have sharp differences in educational and health outcomes such as Westport and Bridgeport or New Haven along the divide between the Prospect Hill and downtown communities. Robby Hill ’24, who is working as a volunteer for Desegregate CT on his gap year, explained that in Connecticut “it is 3 to 5 times more expensive to live in a zip code with a high performing school district than it is to live in a zip code with a low performing school district.”

Zoning laws are outdated: Many people now, especially young adults, do not want to live in large, single-family homes and are instead looking to live in apartments, mixed living housing or walkable communities. Higher density housing, built on less land per unit, is cheaper too. Outdated zoning laws also contribute to environmental problems; Connecticut uses too much land for homes, cutting into forests and farmland, and minimum parking requirements have been found to increase automobile dependence, contributing to higher carbon emissions.

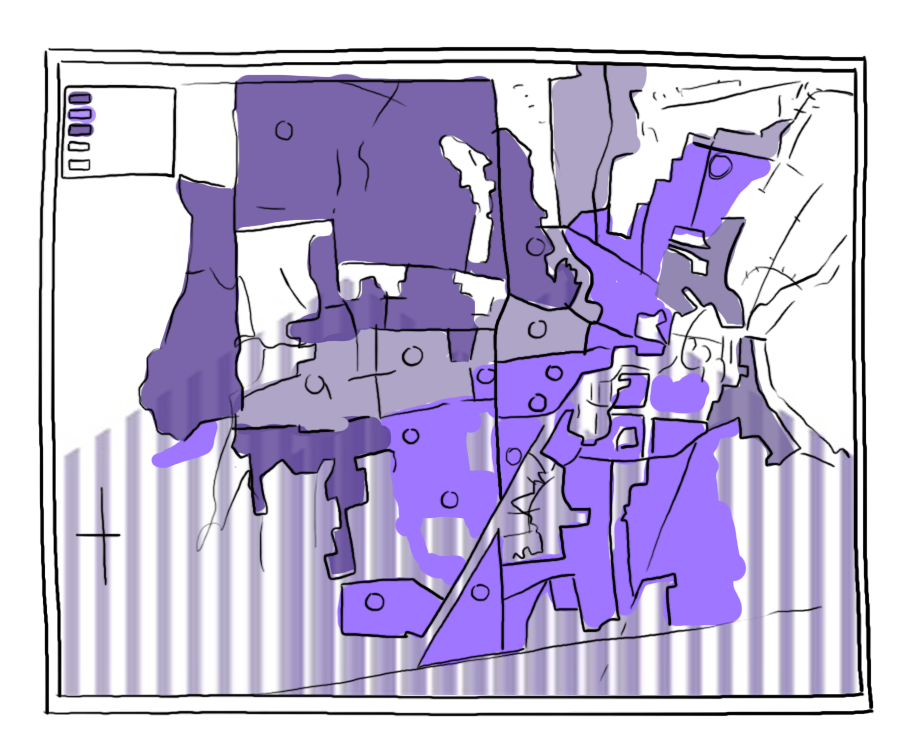

Desegregate CT’s work centers around seven policy proposals, some of which have been implemented by other towns in an effort to facilitate more equitable communities: permitting accessory dwelling units, transit oriented zoning, reduced parking mandates, model codes for buildings and streets, commissioner training and housing on main streets. “All of these are ideas that many towns in Connecticut already adhere to, but we’re just trying to rein in some of the outlier towns and put together proposals that are good for the state as a whole, and that will help break down residential segregation,” said Hill. One of the newest projects that Desegregate CT has completed is the CT Zoning Atlas, which a number of Yale student volunteers have helped create as a part of the Yale Roosevelt Institute. The CT Zoning Atlas provides residential zoning information for all of Connecticut’s 2,600+ districts and two subdivision districts, as well as demographic information like median household income and BIPOC population numbers. The atlas reflects changes in district boundaries and regulation. Josephine Cureton ’24 explained the process of the project: “We gather data for town planners. The first step is preliminary data collection and going through zoning and business codes, and then we translate that data in recommendation score cards that we can send out to Connecticut’s municipalities.” The map is a visualization of all the collected data that informs planners how the zoning laws prevent the possibility of building equitable and affordable housing. “Actually visualizing the data on the atlas made me realize how impactful the project is, since before I had just been gathering data on land laws instead of how people can and can’t live,” said Cureton. “The goal is to allow for more developments on main streets and among business centers so that cities and towns don’t have to build into natural areas, as well as making sure to add density to the main parts of the city so people can enjoy its benefits and not cut into natural land,” said Cureton.

Advocacy for affordable housing is happening across the country and Desegregate CT volunteers regularly speak to representatives of similar organizations in Massachusetts, New York and California to exchange ideas. “A key feature of Desegregate CT’s platform is that we are not the first people to be doing this — these are understood and agreed upon ideas,” said Hill. When asked what the biggest problem Desegregate CT encounters as a new organization fighting for zoning law reform, Hill said that there is a “lack of knowledge in the general public of what zoning is and how it affects our lives; the CT Zoning Atlas is then a representation of how these laws contribute to our lives.” These laws have consequences for future generations of New Haven and Connecticut residents; “It doesn’t stop with our platform — there is more we can do either on the state level or through lobbying in local zoning commissions,” said Hill. “While there are immediate policy goals for our upcoming legislative session, there’s always more we can do to make communities more inclusive.”

Julia Levi | julia.levi@yale.edu