Courtesy of Jessenia Khalyat

On July 26, 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act, which extended protections against discrimination to people with disabilities, was signed into law. In its 30-year history, the ADA has facilitated strides in educational accommodations and workplace accessibility for people with disabilities, but there is still work to be done, even at Yale.

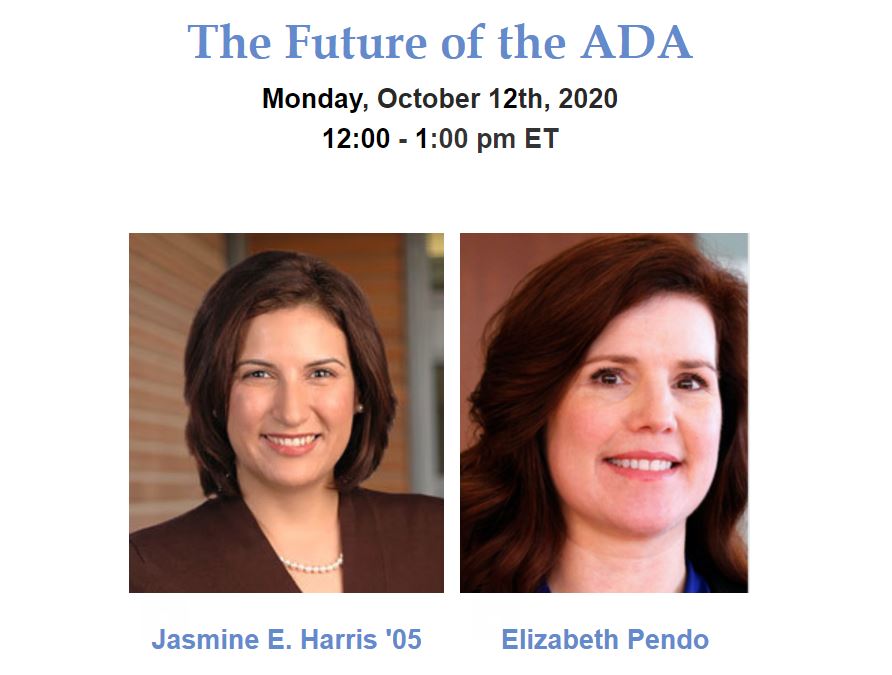

The Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy is hosting a yearlong Zoom series called “ADA @ 30” to examine the history and legacy of the ADA. In the latest installment on Monday, two disability law professors, UC Davis’ Jasmine Harris LAW ’05 and Saint Louis University’s Elizabeth Pendo, discussed the past, present and future of the ADA. After brief presentations by both Harris and Pendo, the panel moved to questions prepared by law students who are members of ThinkDifferent, the law school disability affinity group. The conversation was moderated by Natalie Nogueira LAW ’23, who also facilitated the open Q&A afterward.

Harris and Pendo spoke about the ADA and its relevance to healthcare, education and the workplace in light of COVID-19. Disability rights are particularly relevant now because of the intersections between race and disability, healthcare access and disability, and more. Despite the many challenges associated with COVID-19, Harris framed this time as an opportunity to reimagine the “way we have ordered the world.”

“People have said, ‘Gosh, you know disability rights — they’re important, but in order to make concepts like universal design a reality, we need to hit a stop button,’” Harris said during her presentation. “And we can’t ever just hit the pause button and rethink the way in which we do business, the way in which we develop services, the way in which we educate. Well, guess what? COVID-19 is our pause button.”

Accommodations that people have requested and been denied for years, such as recorded lectures and remote work, are now widely available. But according to Pendo, it remains to be seen what lessons people take from the pandemic in the long term.

“We don’t have a consensus amongst the circuits as to how our accessibility requirements apply to digital spaces,” Pendo said in an interview with the News. “We have a voluntary set of best practices that have been developed.”

Accessibility was a major consideration in planning the event itself.

“Zoom makes it really necessary to have built-in closed captioning in order to maximize the accessibility of the event,” President of ThinkDifferent Madison Needham LAW ’21 said. “For all of our events, we’ve gone out of our way to secure a closed captioner and make sure that the video is [as] accessible as possible. People are also encouraged to reach out to me if they have other accessibility needs and we’ll make whatever adjustments are necessary.”

During the event, closed captioning was visible for everyone, not just those who requested it. According to Harris, this is an example of universal design, intentionally creating environments that can be accessed by the maximum number of people, regardless of disability or other factors.

“As a deaf person, this is a welcome change. Thank you,” Russell Kane, an attendee at the event, typed in the chat. According to Kane, no other Zoom lecture he has attended has provided automatic live transcription. This led him to drop out of a law program earlier this semester. He is currently in the process of applying to Yale Law School for fall 2021.

Universal design and accommodations can also benefit those without disabilities. Closed captioning during class can help people follow the conversation and focus on what is being said. Similarly, according to Pendo, accessible medical supplies can also benefit people of short stature, children, the elderly, and people with a temporary injury.

“All ability is temporary,” Ben Bond DIV ’22, co-chair and founder of DivineAbilities, a co-sponsor of the event, said. “Therefore, we all have a stake in dismantling ableism. Because our bodies are so fragile, and it manifests itself in ways that we can’t even begin to understand.”

Looking forward, the 2020 elections are vital for the continued effectiveness of the ADA, according to both Pendo and Harris. A presidential administration’s view of civil rights and inclusion impacts its agenda and willingness to defend challenges to the ADA in Congress. Questions about healthcare and the rulemaking processes that help enforce the ADA will be decided by the officials Americans elect next month.

“If you see it [disability rights] as special treatment, then you’ll see it very narrowly,” said Pendo. “You’ll consider cost more important. You’ll think of it as applying to a narrow group of people. But if you think of it more expansively, as it was intended, to correct past wrongs and to provide a level playing field, then you’ll see it as something that should grow and thrive and develop and apply in new ways.”

The event was a collaboration between the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy, DivineAbilities, Graduate Student Disability Alliance and ThinkDifferent.

Serena Puang | serena.puang@yale.edu