Roxanna Andrade

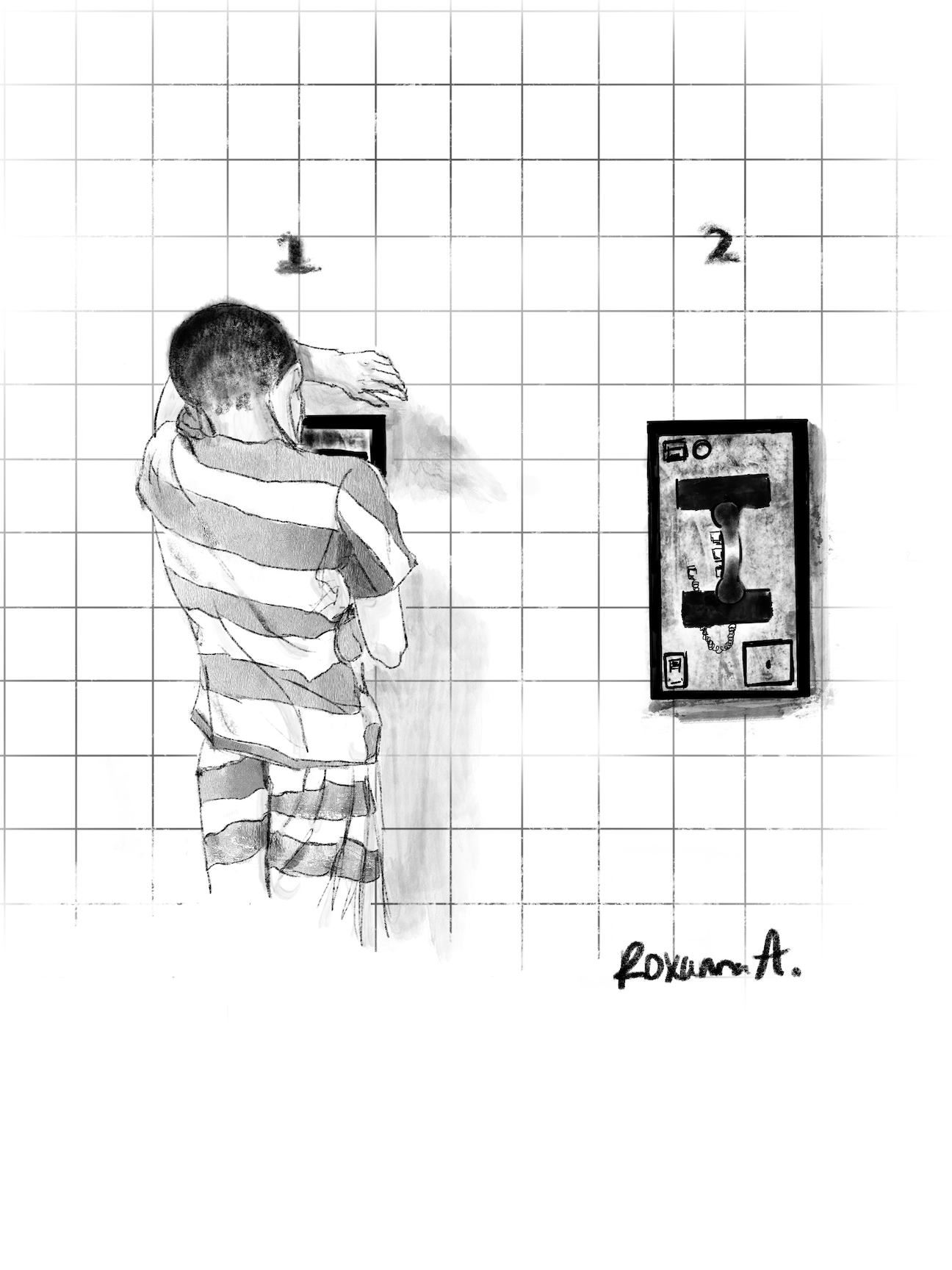

During Jovaan Lumpkin’s 11 and a half years in prison, his mother never missed the phone bill.

Jovaan, a 34-year-old Hartford resident, was incarcerated for the first time when he was 17. He served three sentences at Macdougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Suffield, Connecticut, a maximum security prison for adult men and the largest correctional facility in New England. He was discharged from a halfway house this past December. In prison, he called his mother two or three times a week — a show of her unflagging devotion. Still, the steep cost of visits and phone calls was prohibitive for other loved ones. Jovaan was no stranger to loneliness.

“It gets hard, especially around the holidays,” he admitted. He still spoke about prison in the present tense. Jovaan is currently a student in a re-entry program at Manchester Community College and an employee at a movie theater in Hartford. But reintegrating himself into society is an ongoing process. As he put it, “It’s a big world.”

“For about 11 of the past 15 years, I’ve been in a small world. A real small world,” Jovaan said. “But I’m doing good. I’m finding my way.”

We met Jovaan’s mother Diane Lewis at the Hartford Legislative Office Building, where she was giving public testimony about her experience paying for prison phone calls. She stopped our interview to pull up pictures from her Instagram page of Jovaan on the day he came home from prison, as well as photos of his 8-year-old son. The day of our interview was Jovaan’s first day in the re-entry program at Manchester, where Diane works.

Diane was banned for four years from visiting Jovaan in prison after she “got in a verbal war” with one of the correctional officers. “The COs are asses,” she told us. For those four years, she could not touch or see her son, and she communicated with him only through phone calls.

Diane works multiple jobs and lives paycheck to paycheck. Paying to speak to her son every month came at a cost. Her lights went out, her gas was cut off and she fell behind in her rent. When her car broke down, she could not afford to fix it. But Jovaan never knew. Diane ensured that he remained singularly focused on the goal of coming home.

“If going hungry allowed me to make my son happy for 15 minutes a day, then so be it,” Diane said. She never wanted to make Jovaan feel like a burden: “When you’re a mother, kids don’t really know that you don’t have shit.”

Diane — who has three children in addition to Jovaan — attributes her son’s successful release from prison to his enduring connection with his family. Jovaan kept in touch with friends in prison, but his mother said that “over time, the friends disappear,” and he came to rely primarily on her for communication with the outside world. She added his two younger sisters to her phone account so they could talk to him, but most of all, Jovaan could trust that Diane’s phone would be on.

“I love him with everything in me … he was missed immensely,” Diane said of Jovaan, who is her oldest child. “But we knew that he was feeling worse than any of us would ever feel, and he needed us to keep him uplifted. We knew that we would keep any bad news away from him.”

Diane knows horror stories of mothers who could not afford to call their sons during their prison times, when the cost of communication stoked resentment and severed family relationships. She sees this as one of the gravest tragedies of the American prison system.

Diane also urges empathy for parents who don’t have the economic resources to pay phone bills at all, even if they make the excruciating sacrifices she did. “It’s about every mother,” she said. “I know people that can’t talk to their kids ever.”

****

According to a 2019 report by the Prison Policy Initiative, Connecticut currently ranks 49th in affordability for the cost of prison phone calls. Since 2012, the state has contracted with Securus Technologies, a national prison telecommunications corporation, which Worth Rises — a nonprofit advocacy group working to dismantle the prison-industrial complex — describes as “the most predatory correctional telecommunications company” in the country.

In 2018, Connecticut families paid $13.3 million for phone calls with incarcerated loved ones. It cost around $5 to make a 15-minute phone call. The state collected a $7.7 million profit from these costs, and the remaining $5.6 million went to Securus.

In February 2019, State Representative Josh Elliott worked with Worth Rises to introduce House Bill 6714 in Connecticut. The bill would provide free phone calls for incarcerated people, and the Department of Corrections would not receive revenue for the provision of any telecommunications service.

Rep. Elliott says the genesis of the bill came from a prison visit and a conference. In 2017, he visited Cheshire Correctional Institution, a level-four maximum security men’s prison in New Haven County. Elliott, who earned a bachelor’s in sociology with an emphasis on criminal justice from Ithaca College, was already well-informed about the prison-industrial complex. But at Cheshire Correctional, a few details struck him: the majority of the inmates were men of color, everyone there was serving time because of a parole or probation violation, and prisoners there made 1 million license plates a year, earning only $0.75 to $1.25 an hour for their work.

“It sort of smacks of slave labor to me based on all those different issues,” Elliott said. “And I wanted to begin having a discussion of what it looks like to create a minimum wage for people who are incarcerated. This is to equate money with labor, it’s to give people something to fall back onto when they’re released so that they have better rates of re-entering society.”

Earlier in 2017, Rep. Elliott attended a conference called Young Elected Officials. There, he met Bianca Tylek, a prison abolitionist and the founder and executive director of Worth Rises. They stayed in touch, and around a year later, Elliott reached out to her about the issue of setting a minimum wage in prisons. Together, they spent a few months brainstorming ideas, reaching out to law professors and creating a thorough platform for criminal justice reform in Connecticut.

“I was trying to be conscious of not doing the same work that other people were already doing,” Rep. Elliott said. The platform he and Bianca came up with included eight reforms. When they showed the list to the chair of Judiciary, he pointed to their plan for free prison telecommunications as the most immediately feasible. As such, they made this issue a priority for the 2019 legislative session.

“There’s a bill like this being introduced every few years and well, it just never really got anywhere beyond introduction,” Bianca said.

This time around, though, the political climate was different. Citing the recent national spotlight on criminal justice reform, Rep. Elliott noted that they “were in more fertile ground to get an issue like this moving.” San Francisco and New York City had both recently passed bills making prison phone calls free. New York City — the first city in the U.S. to pass such a measure — also contracts with Securus, so passing the bill meant that the city stopped collecting the 5 million dollars it had annually received in commission fees.

“We’re working on the backs of so many people who have done tremendous work on criminal justice in the state of Connecticut and nationally,” Bianca said of the bill’s progress.

Last year, Rep. Elliott passed his proposal for free prison phone calls through the Judiciary Committee and the Appropriations Sub-Committee that considers criminal justice issues. The bill received positive attention from the press and politicians, including former presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren. In the final week of Connecticut’s 2019 legislative session, HB 6714 made it into the House omnibus bill, which packaged together several unrelated measures. The bill failed for reasons unrelated to HB 6714, and though he tabled a final vote, the House Majority Leader pledged to prioritize the bill in the 2020 session.

*****

A coalition of activists flocked to join Bianca and Rep. Elliott. Nonprofits rallied behind their cause, including the ACLU of CT, the CT Children with Incarcerated Parents Initiative and the racial justice advocacy group Color of Change.

“A big effort by Bianca and myself,” said Rep. Elliott, “has been to make sure this becomes more of a locally-led initiative, so that we don’t get hit by the criticism that this is an outside advocacy group trying to do work in Connecticut.” In addition to working with other nonprofits, Bianca and Rep. Elliott sought to build a movement centered around the experiences of Connecticut residents directly impacted by the criminal justice system.

Though Bianca says Worth Rises has no uniform “day-to-day operations,” one of the key tasks of the organization is to connect with these affected people and mobilize them. “It’s a close community of folks,” she said. Worth Rises reaches out to incarcerated people, asking them to write their legislators and tell their families to get involved with the organization. “We’ve got a lot of folks inside engaged,” Bianca said.

Bianca first met Diane Lewis at Hartford Night, an annual celebration that each Connecticut city holds at the Legislative Office Building. Bianca was there to connect with community members. Diane was there for another reason. “You know how they have all the free food in the lobby? That’s why I was here,” said Diane, who was hungry because she had just paid the phone bill for the month and didn’t have enough money for food.

When Bianca spotted Diane at the fair, she immediately knew she would be instrumental in the movement. “I saw this woman with this shirt that said ‘People Not Prisons,’ and I said ‘Oh, she’s definitely our people,’” Bianca recounted. “Diane’s been our everything ever since … she’s like my hero.”

Diane was already a criminal justice activist, serving as the communications director for a social justice organization and working on the training and employment of formerly incarcerated people. But she had never considered advocating specifically for free prison phone calls until Bianca spoke with her.

Diane’s rationale for joining with Worth Rises was simple: “Love don’t cost a thing,” she said. “To tell your kids you love them should be free.”

****

One enduring obstacle to achieving major criminal justice reforms is the role of corporate interests in lobbying. According to Worth Rises, lobby registration documents showed that Securus spent $40,000 lobbying the Department of Corrections and the governor against HB 6714. While advocates pushed Securus to withdraw their opposition to the bill by May 2019, many believed serious damage had already been done.

Bianca and Rep. Elliott say most of the opponents to the bill are preoccupied with the cost. Indeed, some state officials raised concerns that the loss in commissions would force the state to cut services that had previously relied on the revenue raised by the prison industry. Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont released a new budget on February 6, in which he allocated $5.5 million to make up for the lost revenue of lowering the cost of prison phone calls. Bianca and Rep. Elliott celebrated the victory but warned against complacency. The campaign is not about lowering barriers to communication; it’s about eliminating them entirely.

“Making some progress is better than making no progress, but there is a concern … that incrementalism will not work,” Rep. Elliott explained. “We need to have assurances that if we make some progress, we will actually continue working on this issue.”

Lamont’s new budget addresses some financial concerns, but opponents of the bill worry the remaining millions are unaccounted for. Bianca doesn’t buy it: “It’s frustrating to hear excuses for doing the right thing. Everybody always brings up the money, and we know that money gets allocated based on people’s priorities and what people care about. Money’s not endless, but it’s also not short.”

In response to financial arguments, many advocates emphasize that family connection improves re-entry outcomes, which will lower net costs in the long term. “We spend so much money on various programs to ensure the success of folk that deserve a second chance,” Elliott said. “Why would we view this any differently? Because we know that when people stay in touch, when families stay in touch, then you are just so much more likely to be successful.”

Phone calls do more than just improve outcomes after release. While he was incarcerated, Jovaan, Diane’s son, noticed a difference between those who could speak with their families and those who could not. “A lot of people don’t get in trouble because they want to be able to talk to their loved ones,” he said. “When you don’t have that, you’ve really got nothing to behave for … a lot of the more aggressive inmates were the ones that weren’t getting the visits, weren’t getting the phone calls.”

Such observations equip activists with two argumentative strategies. One argument is based on statistics: when incarcerated people communicate with their family and friends outside, they have more success reintegrating into society and a lower chance of committing another crime. The other argument is one of moral outrage: denying families the right to speak to one another — treating human connection as a financial burden — is cruel and unnecessarily punitive. The costs of such a policy fall on the parents and children of incarcerated people, who are already struggling with family separation.

Bianca, Rep. Elliott and other activists emphasize this latter point. “I think keeping families connected is the strongest thing about this,” Elliott said.

****

On February 13, Worth Rises hosted a press conference at the Legislative Office Building to launch their 2020 campaign Connecticut Connecting Families. Around two dozen activists and community members stood in a line around a podium, some of them holding signs with Diane’s words: “Our children deserve to hear ‘I love you’ too.” They faced a large audience, including other activists, journalists, legislators and representatives from the Majority Leader’s office, Sentencing Commission and Judicial Department.

A handful of speakers shared their stories before Bianca stepped up to the podium. “Today we are fighting to protect families — our most precious and foundational institution,” she told the room, explaining the campaign as a fight against Securus’ corporate greed. “We are looking forward to working with the legislature this session to finally get this across the finish line,” she said. “And we all have the confidence that it will happen.”

When the applause died down, Bianca pulled out her cell phone and announced the activists had a song prepared. “This Little Phone of Mine” was the title. “This little phone of mine,” the activists sang. “I need to hear it ring.” They waved their phones back and forth. “This little phone of mine, I need to hear it ring. Let it ring, all the time, let it ring.”

Once the conference ended, the group dispersed. They milled around the conference room, hugging and exchanging words of support. It was clear that the activists fighting for free prison phone calls have no plans to pack up their bags if and when the bill passes.

“I see this as so much bigger than just getting this done for Connecticut,” Elliott said.

****

Rep. Elliott seeks radical transformation — a change in the fundamental logic of the criminal justice system.

“The whole legal system in Connecticut is just fucked up,” agreed Keith Soto, a formerly incarcerated New Britain resident who gives talks with the Connecticut Department for Children and Families. “It starts with misunderstandings of culture.”

The costs of phone calls prevented Keith from talking to his daughter as much as he would have liked to during the almost 12 years he spent in prison. “It put a wedge between us,” he said. “She felt like I abandoned her when she needed me.” When we interviewed him, Keith was on the way to counseling with his daughter.

“Prison is not rehabilitation,” said Michael Manson, a Hartford resident who served over three years in prison. “It’s like babysitting. It’s like a big time out. They’re not trying to help you change your behavior.” Michael thinks this strips prisoners of their humanity, and he has worked to increase mental health services in prisons.

When he was incarcerated, the cost of prison phone calls made it so Michael went a month without speaking to his mother, who has severe health issues. Michael emphasized how important phone calls are to the mental health of prisoners, telling us that calling people back home enabled him to “mentally get out of prison,” even if it was just for a few minutes.

Rep. Elliott hopes to represent residents like Keith and Michael, noting how the criminal justice system punishes poverty, criminalizes people with mental health issues and targets black male youth. “The goal would be, let’s change the way we view our system so that when people go in, they can leave with a better chance of successful re-entry,” he said.

For Rep. Elliott, Bianca, Diane and the activists who work with them, phone calls are an important first step. Diane knows firsthand how important this legislation is to making sure people can have successful lives after prison. “Jovaan being able to talk to his family and know we love him made him work to get home, to do the programs, to work his job,” she said.

After Jovaan spends some time getting accustomed to life outside prison, he hopes to be like his mother: an advocate for criminal justice reform. And it’s obvious that Diane chooses the lifestyle she does — balancing multiple jobs with work as an activist — because she loves her son. Life after prison is far from easy, but Jovaan and his mother have grown closer without the burdensome costs of communication.

“Now, I talk to her every day,” he said. “I just pick up the phone and text.”

Ella Goldblum | ella.goldblum@yale.edu

Andrew Kornfeld | andrew.kornfeld@yale.edu