Dora Guo

It’s an omnipresent trope to ascribe activist intent — with varying legitimacy — to theater. In a world wrought with political tumult, this approach is a popular way to endow a show with broader resonance. But it’s hard not to be skeptical of this lofty goal: much “art for social change” fails to deliver on its promise.

Enter “Manahatta.”

This new play by Mary Kathryn Nagle achieves its political ambitions through double casting, which reframes key narratives of Native American experience by grounding universal issues in intimate relationships, maintaining a multi-issue agenda and redefining home as a history, not a place.

“Manahatta” includes two separate timelines: first is the story of Jane Snake — a young woman who just might be the first Native American on Wall Street — and her family in Oklahoma. Then, there is the story of Jane’s ancestors on the island of Manahatta, the Lenape people, facing the violence of the Dutch East India Company. Switching between these periods, “Manahatta” tells a tale of destruction: in the modern era, the Snake family weathers the 2008 financial crisis; in the 1600s, the Lenape people struggle to save themselves from manipulation and massacre by the Dutch colonizers.

As the story progresses, Nagle weaves in many different aspects of Native American life. Characters address the perils of preserving the Lenape language, Christian missionaries’ role in Native American assimilation, white male predation on Native women, the tokenizing experience of breaking the glass ceiling, and cultural genocide inflicted on Native children. Nagle also touches on slavery, alcohol, border walls a la “MAGA,” being gay in a church, healthcare costs and Adjustable Rate Mortgages, among other things.

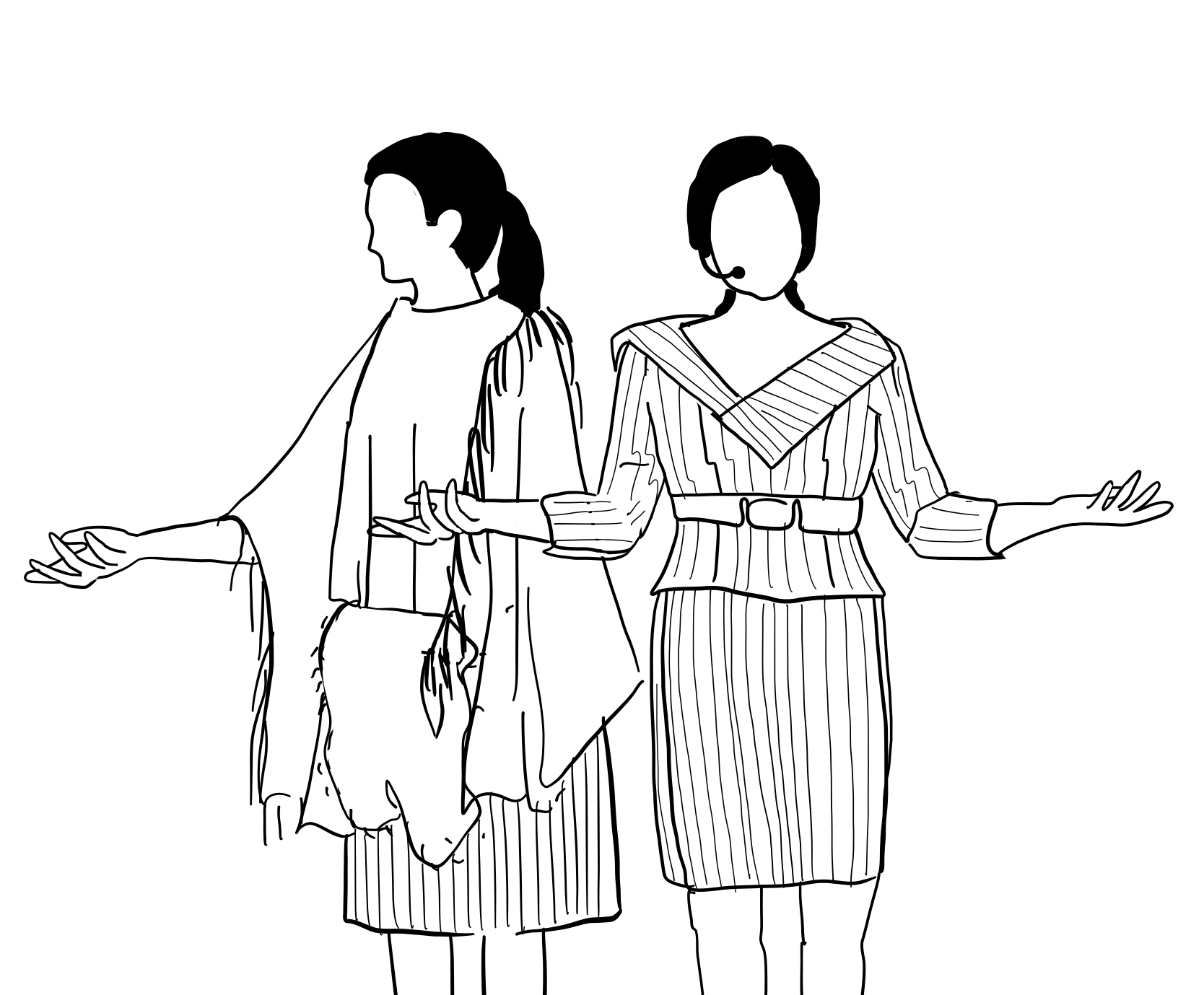

It’s a lot to cover. But the play’s audacity pays off: Nagle doesn’t shy away from addressing so many vital issues, and by doing so, she paints an intricate portrait of the narratives that underpin Native American life. What allows these themes to jell are the historical echoes Nagle incorporates via double casting: each modern character has a counterpart in the past timeline. Jane Snake, the protagonist who ascends to power in Manhattan, is played by the same actress as Le-le-wa’-you, a Lenape woman who trades fur with the colonists in Manahatta. Joe, the Lehman Brothers executive who bumbles through mea culpa allyship, is paralleled by Jakob, a Dutch settler who, despite sympathizing with Le-le-wa’-you, barely hesitates to murder her loved ones.

The story oscillates fluidly between these chronologies: dialogue repeats and overlaps, actors change costumes onstage, scenes bleed into each other seamlessly. The two worlds coexist and intertwine with one stage, one set, one cast.

The purpose of this parallelism must be contextualized with the playwright’s background: Nagle is a partner at Pipestem Law, where she advocates for tribal sovereignty; her belief in the power of theater is clearly informed by her legal ethos. In an interview with “Shondaland,” she described her understanding of legal activism as an issue of story: since the laws that harm Native American people “are based on false narratives,” the way “to really counteract them is to change the narrative through storytelling.” As important as precedent, Nagle claims, are the stories we choose to believe about the laws that govern us.

So Nagle confronts these narratives. In “Manahatta,” dual-casting parallelism — which is “not optional,” according to the playwright — challenges the historical amnesia that cleaves the past from the present. By overlapping the set, characters, costumes and scenes of “Manahatta,” Nagle forces us to understand that the problems of Native oppression are perennial, rooted in Colonialism and enduring through the present era. Nothing in “Manahatta” is isolated, and no action is decontextualized from its precedent.

This structure allows the power dynamics in “Manahatta” to recycle through disparate contexts: in the 1600s, the Dutch guile the Lenape into selling their ancestral lands on the grounds that natives will never understand the concept of ownership; in the 2000s, a bank offers Bobbie (the matriarch of the Snake family) a shoddy mortgage that costs her the house the Snake family has inhabited for generations — the banker, confident that Bobbie will never grasp the economics of home ownership, neglects to explain the dangers of the deal. Themes of control, manipulation, and greed permeate every interaction between the mighty and the disempowered, telling a compelling story about a Native American experience that might vary in specifics, but persists in its most devastating effects.

When Bobbie loses her home to foreclosure, Nagle reminds us of the brutal ways Lenape people have been evicted throughout history. This culminates in perhaps the most potent moment of the play, when Jane offers to pay off her mother’s debts, and Bobbie refuses the money — how could she accept cash “made from all those other idiots who got loans they can’t repay”?

This is a specific story about Bobbie, Jane, and predatory lending. But its resonance broadens when it is posed next to a scene between Le-le-wa’-you and her mother, in which Le-le-wa’-you gushes about trading with the Dutch for “more” wampum, and her mother replies, “We trade with, not for, wampum.” Modern Jane enters antihero territory, becoming a workaholic Wall Street shark, echoing the greed of the Dutch East India Company and straining for more. Here, Nagle’s point is clear — perhaps our protagonist has succeeded, but she’s done so by selling out, by extorting the innocent, by forgetting her culture and the people she loves. This is what “Manahatta” does best: it contextualizes complex power structures in intimate relationships.

As these themes develop, Nagle stays true to her story-for-social-change aim. She resists the urge to shoehorn her activism into a single, pithy mission statement. If some of the topics of “Manahatta” lack full exploration, it is only because the playwright sees so many Native American histories that need rewriting. To paraphrase Audre Lorde, “Manahatta” is not a single-issue play because its characters don’t live single-issue lives. Sure, narrowing the show’s thematic scope would allow for deeper examination of its subjects. But it would do so at the expense of historical justice.

Nagle portrays a myriad of experiences that reflect a wide range of truths: that the past matters, that trauma repeats itself, that stories — especially the ones that tell us nothing ever like this has ever happened before, the ones that justify deeply-rooted evils — matter. “Manahatta” takes on a world of false narratives, and, like its protagonist, it isn’t afraid to be ambitious.

Yet Nagle never loses her laser-sharp devotion to her characters. We are grounded in the Snake family, in the 1600s Lenape tribe. While addressing large-scale Native American causes, Nagle always remembers the people for whom she is advocating.

Perhaps it is this duality — the coupling of the intimate and the grand, the distant and the visceral, the bold goals and the delicate approach — that makes “Manahatta” such a powerful work of activist theater.

As Jane becomes caught up in the flurry of capitalist hedonism, the journey of Le-le-wa’-you dramatizes the world she is leaving behind. This culminates in the denouement, when Bobbie gifts Jane a sacred family wampum, a prescription that Jane remember who she is. At the heart of “Manahatta” is homecoming — home to one’s roots, to one’s values, to one’s past.

We end on Wall Street in 2008, this time with Jane wearing the sacred wampum Le-le-wa’-you might have carried as she fled her Dutch-occupied homeland. All the loose ends of the narrative come together with a resounding message of return: “Machi! Machi Manahatta!”

Go home! Go home to Manahatta!

Zoe Larkin | zoe.larkin@yale.edu