Tonight the sky reminds me of Vincent Van Gogh. There’s thunder, then a pause. The lightning casts the sky a yellow-white. It’s not yet raining, and the air is still. We’re in Avignon, a town in southeastern France. It’s November which is important because nothing is in demand. Everything is inexpensive. My seventeen-year-old sister laughs at me because I booked us a room on a houseboat rather than a hotel for the night. It’s the one night it storms hard. We’ll feel the river swell. My father says it’s just fine. We arrive like this, in the damp air, all speaking at once. It’s 6 p.m. and already dark. The ramp down to the water is slippery. Our French is broken in different ways. The man who unlatches the gate by the water says he’s impressed we know any at all, being Americans. He shows us to the helm of the boat and opens a trap door to our accommodation.

The boat is anchored off a small island in the Rhone River. Tomorrow, we will see the green water from above when we follow tourist signs to the garden in the Palace of the Popes, up on the top of a hill. The garden, crowned with a statue of a pope raising his golden hand, will be abandoned except for a few gardeners collecting brown leaves and tending to the pond’s water.

The whole trip is like this — like traipsing around movie sets once the show’s already been shot and sent in for production. We walk the bends of each town at our own pace, whisper about the sweeping pastels of the Rhone Valley. I’ve never been a tourist this way, silent with my surroundings and alone with them.

We came with no plans besides bookings for a room each night. Each day, we drive the main highways, and I keep a guidebook with me in the back seat, occasionally reading excerpts aloud. Yesterday, we exited the highway for a wine tasting. The lobby was predictably still. My skin jumped when a woman walked in and took her seat behind the reception desk. She opened a bottle of red with a new contraption she told us she’d never had an occasion to use. The machine slides a needle through the stopper’s cork so the rest of the wine will keep longer. She fumbled with the pump before securing it on the bottle’s neck. We sampled the spread and left, laughing heartily at the whole ordeal. “Wine tasting in the south of France,” we said out loud when we’re back in the car, letting those images stumble over the currently passing scenery. No sun breaks through the clouds; no bicyclists giggle along the street with jostled bottles rouging their forearms.

During our day in Arles, we read about Van Gogh’s work as an excuse for our meandering. We didn’t have much of a reason for coming to this country. It’s Thanksgiving week. We all have free time. The ticket cost about the same as one home to Los Angeles, and we didn’t have a great place to return to anyway. We’re thankful when we have to slow the car at another entrance to the A7. It’s a pleasure to loiter in the familiar hum of traffic. We roll down our windows at the roundabout and honk at all the citizens in yellow vests who raise hamburgers beside their bonfires in the middle of the turnstyle. Trucks are lined up, can’t budge. Some tires are on the ground as seats for the protestors at this manifestation. Two weeks from now, the Arc de Triomphe will be vandalized, cars will be burned, storefronts smashed. There will be consideration for a state of emergency. But now, it’s friendly traffic on vacation and a people who mobilize quicker than Americans. We shake our heads, move a yellow vest from the glove compartment to the dash, cheer as our car speeds onto the highway.

Van Gogh came to Arles in 1888 with his own excuses — artistic inspiration, new friends, cheap rent. He had wanted to grow a community of painters in his new house — yellow on the inside, yellow on the outside — and he managed one roommate, Paul Gauguin, but their personalities clashed. Van Gogh clipped his own ear.

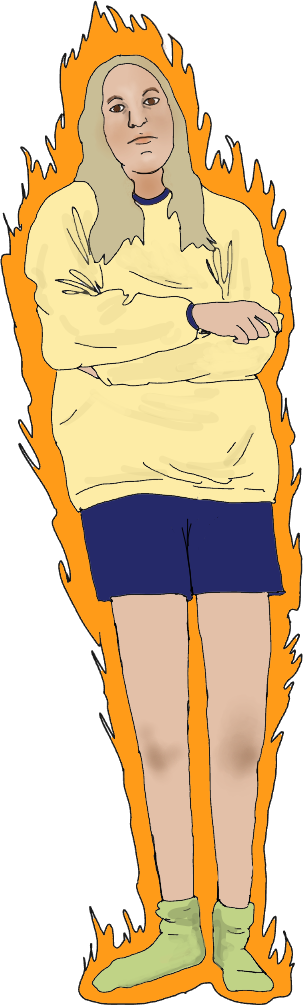

So, alone, the artist would lug his paints and heavy easel. He loved to paint the town at night. He adapted his straw hat to hold light and stuffed candles into makeshift holes. He must have held his core tight to keep the candles from spilling their flames, like a princess balancing a book or a washerwoman with baskets of laundry. With his head wrung like a chandelier, he painted the light he saw.

Van Gogh said there’s no black in the night — “il n’y a pas de noir dans la nuit.” There is dark violet and navy and green, more richness and variety than in day, he said. There’s a painting of Van Gogh’s yellow house on the street in Arles, vantaged to overlook where it stood in 1888. Pausing before it with my gnawed-on baguette and numb fingers, I can recognize the bridge from the background and a steam stack. Where the house once was, there is now a cream-colored sandwich shop. At some point, the legacy paled from the lore. We can’t know anymore if Van Gogh’s house was really so yellow, so bright. We know the painting is. It’s like this with our vacation. Drab, I think, muted, plain living but retold with all the speckles of light.

It rains veils of mist for our entire trip. On the last day — after the wine, the empty streets, the quiet car rides past grey ocean — three hours before driving to the airport, we open a bottle of Moët et Chandon into the street and drink it out of flimsy cups in our rental car. We pour until the bottle is empty and discuss how utterly difficult the traffic has been.

Julia Leatham | julia.leatham@yale.edu