Let me preface this by saying, in the interests of journalistic objectivity, that I lie sometimes. I lie when I represent politics as anything other than a gamble on the future. There are times when I act like I know more than I do, when I walk through step by step exactly what will happen between now and November 3, 2020, and act as if my hesitant bets are nothing other than complete certitudes. But anyone who knows anything about anything will also know that I can’t predict the future.

I love politics, I follow the news nearly obsessively and I’m happy to be quizzed any time. Ultimately, I do believe that politics are personal. Political beliefs and discussions are informed by geography, background, socio-economic status and a litany of other factors. And I believe that political discussions are most powerful when parties recognize the person on the other side of the table and are truly interested in knowing who they are and where they came from.

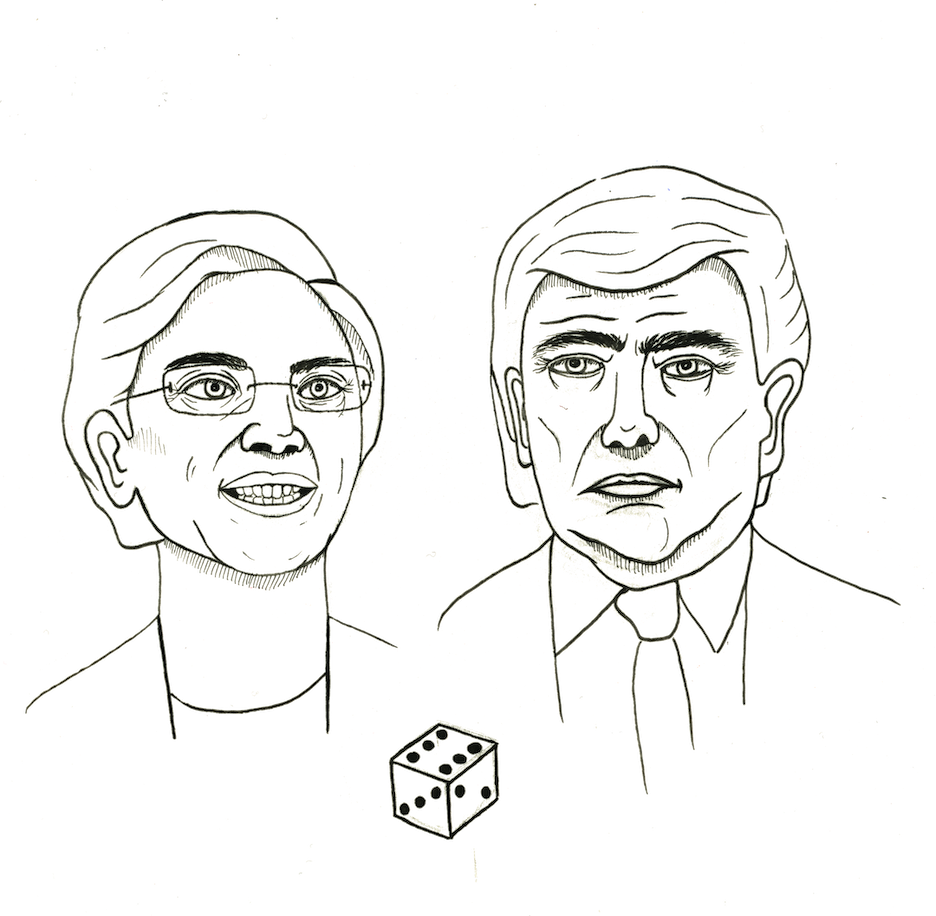

In full disclosure, here’s my 2020 outlook. Like a plurality of Yale students, I plan on voting for Elizabeth Warren. It might be in part a home-state-loyalty thing (I’m from Massachusetts). I first met Warren when I was 12 years old or so. She was filming an ad or an interview by the waterfront, and my brother and I almost walked in front of the camera. Soon afterwards she became Senator. I met her again, more recently and more memorably, at The Book of Mormon in Boston a few months before she announced her run for president. She was incredibly kind, warm and personable. And ever since, I have been her stalwart supporter.

What is most compelling to me about Warren is not her (MANY) policy proposals, not her lectures about the one percent or Big Tech or Wall Street, but her personal history. There is something to be said about psycho-analyzing those who run for president. Warren’s story tells a lot about her.

If you follow the news or have watched any one of the many Democratic debates, you’ve probably heard part of it before. Born and raised in Oklahoma, her father had a heart attack when she was 12 and her mother went to work at Sears with a minimum wage job that sustained their family. Warren went to college but dropped out to get married and have children. Later, after going back to school, she divorced her first husband and got her law degree, eventually going on to teach at Harvard Law.

What she mentions less often is that she was a registered Republican for more than half of her life. Then while she was teaching at the University of Houston she conducted a study with two other academics on why families go bankrupt. She approached it with fiscally conservative expectations: people go broke because they spend irresponsibly. But what they discovered and published 1989 was that many of those who declare bankruptcy are middle class and do so because of variables beyond their control.

A few years later, she registered as a Democrat and became a fierce consumer advocate, going toe-to-toe with then-Senator Joe Biden over barriers to debt forgiveness, establishing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau under President Obama despite enormous opposition, irritating many Washington insiders, and then, despite the odds, beating incumbent Scott Brown to become senator of Massachusetts.

Warren has been criticized on many fronts, most often by being called radical. But I see Warren first and foremost as a pragmatist. Her political evolution shows this, as does her time in the Senate. She is not handcuffed to ideology and prioritizes making tangible change above all else. Behind only Joe Biden and Amy Klobuchar, out of all the Democratic candidates, she has worked on the highest percentage of bipartisan legislation.

Of course, this is not to say that I’m sure she’ll win. I only think that she is by far the best candidate in the field and, whatever the precedent, I have faith in American voters to see that. Polls thus far have shown that as voters get to know Warren better, they like her more. This trend could very well hold going forward.

This period is clearly a pivotal one in American politics and, if we let it, one that will have positive ramifications for generations. We have been shown in the last few years what not to do in politics: not to jeopardize the free press, not to cling too tightly to the establishment, not to approach politics with an attitude of fear or subjectivity. And on the flip-side of each of these is a positive action we can take to strengthen our nation during a trying time.

There are signs that the modus operandi of American elections are changing. Warren and Sanders have proven grassroots, small-donor fundraising, to be the most profitable option available. Doug Jones’ election to the Senate in Alabama and Beto O’Rourke and Stacy Abrams’s near losses showed that the so-called Sun Belt could yield new battleground states. Income inequality has entered the debate with force to be reckoned with.

Ultimately, whatever your party and whoever your candidate, ask what your goals are. Test them, study them, question if they are feasible but, more importantly, if they are substantive. I can’t speak for the rest of the country, but I grow tired of politics when every action is a reaction, when we allow others to decide the frame of debate, when those in debate don’t know their facts.

I’m sure people will disagree with me. I’m a first year who follows politics to pass time. I was raised in Massachusetts, one of the bluest states in the country. But I hope those individuals will engage with me, question my assumptions, while recognizing that our own truths are far from absolute.

Jack Tripp | jack.tripp@yale.edu