Alex Taranto

I write every day but I never write for myself. Not because I don’t have the time, but because I’m afraid. That the words won’t sound right, that the thoughts won’t matter. That I’ll sound too self-involved — which really, I am. Working in LA, away from Yale for the semester, I supplement entertainment industry internships with tutoring four high school students in essay writing. A thousand words of script coverage here, a pile of college admissions essays there, I am always writing — and I’m passionate about it. But almost never do I write for myself. I tell my students, “It’s easy! Just set a timer and force the words out, then edit.”

When combing through my students’ essays, I catch words slipping from my mouth like “ooohhhh” or “it would be so funny if” or explaining one of my comments like “the parenthetical there is a joke.” I lose myself in the worlds of what my students’ essays could be, in the rough edges of what they are. I spend hours dissecting their words, catching typos, clarifying plots, explaining different sentence structures and how they can fill them with details like creating individualized MadLibs. “Parallel this sentence.” “Use a semicolon instead.” “That repetition is good.” “That repetition is bad.” “Finish with a sensory detail from the concert.” “No, find a better verb.” “But what did it really feel like?” I find myself explaining my students’ passions back to them.

This college application season, I read a kid’s essay about sudoku. He wrote something along the lines of: “now I play sudoku instead of opening Instagram.” I read the essay a few times, searching for the life, the hum, the truth beneath the vapidity. I told him that he seems to be good at acknowledging his weaknesses, then working towards his goal in a modified fashion. He agreed and reworked what was there, ultimately scrapping almost everything from the original draft. Every time he introduced a concept, I asked him why or how or when. I probed him with many questions, but always, I asked for more. His ideas percolated like glints of fish underwater. Together, we grasped at them with words, how to lure up each truth until he could read the essay aloud and resonate the words with what lives in his mind. We’d caught a piece of his truth; these are always hidden under some thing or another. Now, his essay is now about learning to break down goals into smaller pieces and working incrementally towards a dream.

Later, I helped the same student, Aidan, shape a sterile essay about his long-term girlfriend into a lyrical recollection. I feel like I know Charlotte now, how she wears bright pops of color, chats easily with friends or strangers, is well-loved, is most likely beautiful and polished in that Beverly Hills way. I could write you an essay on her smile, on her relationship with Aidan. How they will probably break up in college because every time he tries to write what he loves about her it comes up bland. How he’s a lover-boy who sings musical theater on the golf course and is unashamed to reveal this to me. Probably, he will fall in love with the first smile he sits next to in lecture.

I can write you this story because it’s not mine. My knowledge of Aidan’s relationship is limited. I can regurgitate every detail, dress them up with well-paced prose and still have room around the edges. It’s easy to confine myself to editing, to correcting, to molding pieces I’ve been given, to take a limited amount of information and craft a picture, like painting with only primary colors which blend gorgeously into a sunset or a drop of liquid amber on pine bark or the ocean at midnight. It’s easy.

It’s easy to push towards improvement rather than beauty, or perfection, or harmony but these are what I selfishly feel my own thoughts and memories deserve. I’m a romantic and if my first kiss can’t exist graceful enough to balance atop a needle in a hurricane, then how can I let it exist at all?

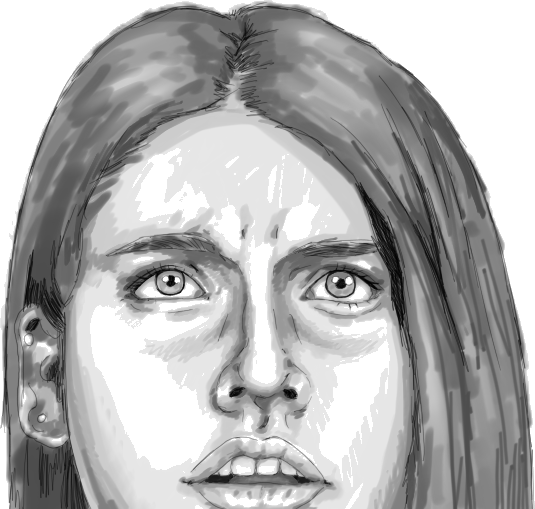

It’s not easy to untangle my own mind. It’s not easy to sit with my pile of thoughts and hold them in my arms, steady. It’s not easy to commit to just one thing, to decide a thought is worthy of my time, of other peoples’ time. My stomach churns at the fear that my words are not worthwhile; it knots, crumples, disintegrates like a page. My mind isn’t a catalogue of essays or scripts, it’s a sprawling room of overlapping half-forgotten images, of transient bursts of light.

I took an improv class this summer and was allowed to attend shows at the theater for free. I watched, I studied. I was surprised to learn that people love stories, period. Not just good stories. People love aesthetics, they love for their minds to be pet, tickled, taunted. People love ASMR, love museums, love hearing the same love story told over and over through each new still-the-same romcom. People marvel at what tastes good in their mind so when people watch improv, they’re pleased to see little happen, to watch a girl cross the stage looking for a lost kitten, quibble with her step-sister, shiver in a snow storm.

People love simple and people love true. They love to hear something and feel “yes, yes, that is exactly right.” In class we built an imaginary room by listing objects that belonged there. Ours: a mini fridge filled with Bud Light, a stained LAZ Boy, a pile of ignored textbooks. On my turn, I said “a personal-sized mini trampoline” and the room responded “mmmmmm.” Everyone knows when it comes to a frat room, that’s exactly right.

I always tell my students to write exactly what they mean in the clearest way they can.et a timer for twenty minutes. No time at all. While they write and I correct, my voice lilts and drops; I sink into the creativity. I overflow with ideas. I tease, color, highlight and explain their thoughts. I buzz. Then I drive home. I park and trudge towards my building, unfurl my body onto my bed. I tell myself, “go brush your teeth.” I tell myself, “read so you can learn.” I flop my feet, shoes still on, atop my covers and watch television, fall asleep—teeth unbrushed, word count abandoned, slip into my dreams in which I’m late to work, running down a sidewalk away from the office building, chatting to a mother and daughter about the hue of the summer sky. I know I’m late, I know I’m headed downhill in the opposite direction of where I should be going, I see the sidewalk and the pale morning sky so cool on my skin; I breathe deep down to my plodding feet trying to steady the buzzing—