Valerie Pavilonis

You know those childhood films that you watch again as an adult and which are supposed to corrupt your childhood innocence? Well, this isn’t one of those stories. I watched “Kirikou et la Sorciere” in French class as a junior in high school. Whether it was my incompetent Francophonic ears or my lack of motivation, the film made no sense to me. I knew vaguely that it was about an abnormally small African baby who saved his village from a witch and her army of “fetishes.” But beyond that, I was perdu.

About a month ago, my suitemate, Mourad, convinced five of us to squeeze onto my tiny Farnam bed to watch Kirikou and the Sorceress (take note of the English title) on my sad, tiny TV. While Mourad wanted to relive a bit of his childhood, I anticipated an hour and a half of confused excitement as had been my experience in my high school French class. I’m glad to say the movie was much better on second viewing. To no surprise, when you speak the language, it’s much easier to appreciate the levels of a film. And we did appreciate it, to say the least.

Kirikou is a 1998 animated European film written and directed by Michel Ocelot that incorporates elements of West African folk tales with motifs of false appearances to show how youthful curiosity breaks the hold of ignorance over society. At the forefront of this tale is the baby, Kirikou, whose small stature does not live up to his braggadocio and wit.

Frustrated with the long nine-month wait in his mother’s womb, Kirikou wills himself into existence and can somehow already walk and talk from the moment of his birth (he even cuts his own umbilical cord). Learning from his mother that the evil sorceress, Karaba, has dried up the village’s spring and devoured nearly all the men, Kirikou sets out to do all that he can for his community that has yet to acknowledge his presence. He fools the witch and saves his uncle, thwarts the witch’s two kidnapping attempts with his alarming strength and speed, and investigates the dry spring, puncturing the engorged monster that hoards the village’s water. In all of these cases, the villagers tease and dismiss Kirikou for his pipsqueak size. Only when he demonstrates his value through heroic feats does the village rejoice and honor him with a catchy earworm.

Seeking wisdom from his greybeard grandfather in the hopes of learning the evil origins of the sorceress, Kirikou repeats the notorious question all parents learn to hate: “Why?” The grandfather commends Kirikou for his curiosity and incessant truth-seeking but says he will eventually hit a metaphysical dead end. However, he says Kirikou is misinformed. The sorceress did not plug up the spring nor devour the men. That is the hearsay of the village not to be believed. The grandfather cautions, “The more the people fear, the more powerful she becomes.” If the villagers sought the truth like young Kirikou, they would understand the motivations of the sorceress and put an end to her apparent evil-doing.

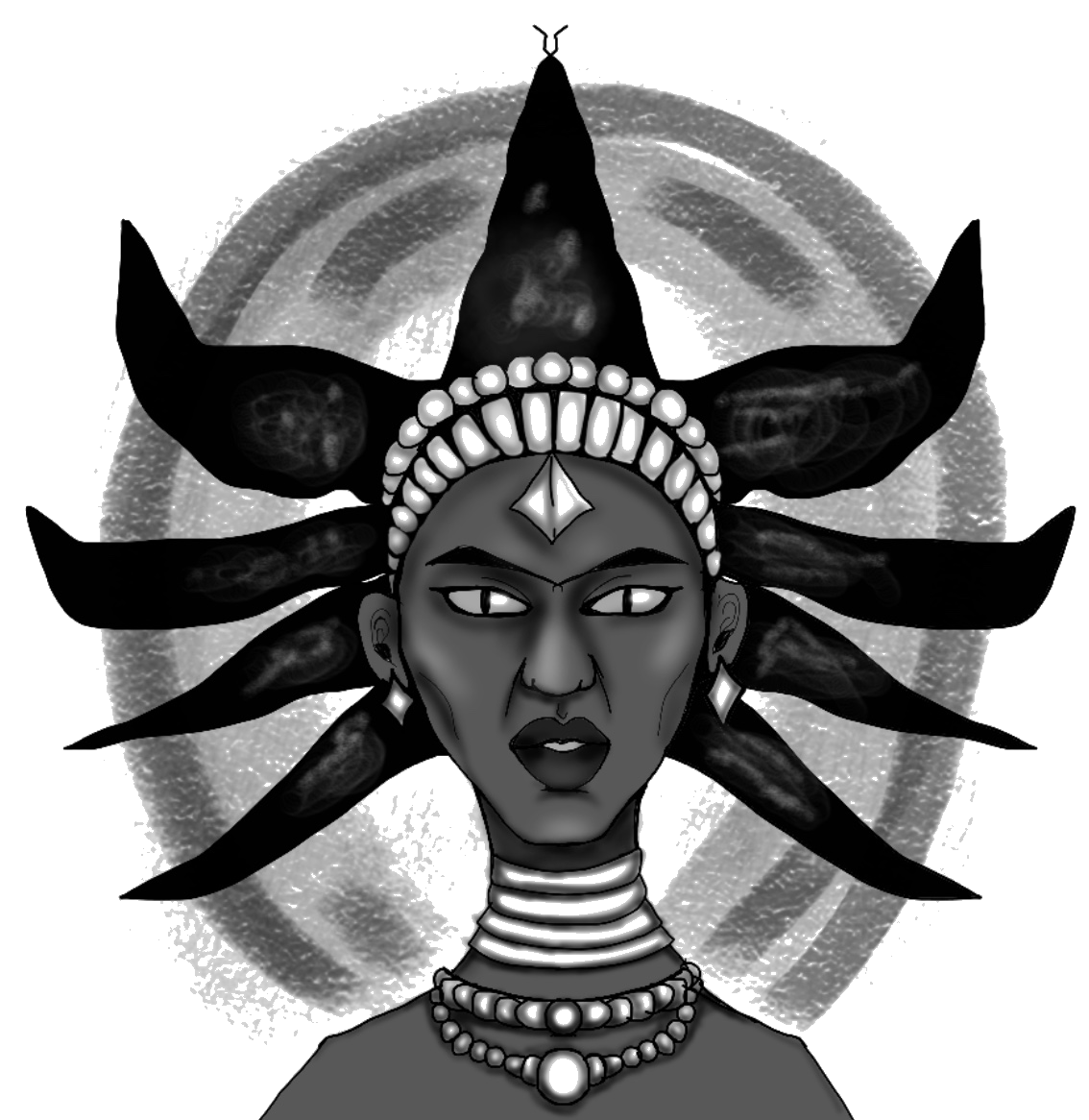

The grandfather explains that the sorceress suffers day and night from a poisonous thorn that a group of terrible men put into her spine. As a result, she dislikes children, has contempt for women and despises men. She will kill anyone who tries to remove her thorn because she does not want to re-experience the original atrocious pain and because the thorn gives her magic powers. Unafraid, Kirikou resolves to remove the thorn or die in the process.

Watching the film with older eyes, I can see that the story is much less absurd than it appears after misunderstanding it in French class. The vengeance of the sorceress can be interpreted as resistance to patriarchal power. The thorn symbolizes the harm that men can inflict on women. After Kirikou removes the thorn from the sorceress’ back, Kirikou demands she marry him. She refuses, saying she will not be anyone’s servant and that he is too young for her. The sorceress is a symbol of the stereotypical third-wave man-hater.

What this absurd tale teaches us is that the whole truth rarely meets the eye. The villagers typecast the sorceress as an evil witch when she is, in fact, an indignant, vengeful victim. Thus, they blame her for the drying up of the spring when it was really the insatiable thirst of an independent animal. They belittle Kirikou as a powerless child when he saves the villagers multiple times. Even the audience is led to believe Kirikou is fearless before he curls up in his grandfather’s lap and says that even as the savior of his people, he is sometimes scared. Outward appearances are deceiving.

Given that appearances can be deceiving, one ought to approach life with a skeptical but generous eye. As hard as it can be, we should not judge each other based on appearances because we’re likely missing something.

Ethan Dodd | ethan.dodd@yale.edu .