Ashley Anthony

Loneliness has become an epidemic for America’s young people. At Yale, loneliness manifests itself in distinctive ways, despite Yale’s community-centered structure and sheer amount of people and opportunities. “It’s hard to feel lonely when you’re constantly busy” may be a common observation Yale students make, but it’s simply not representative of all. Loneliness on campus is a feeling that almost everyone has experienced — especially first years — but it is elusive and difficult to remedy.

From the moment first years step on campus, they are grouped into various assortments of FroCo “microcosms” and “Big/Little” programs and cultural “families.” Understandably, the first year is a critical period when loneliness is especially pervasive, and Yale designed these small circles to help students ease into a new environment. These groups often do result in close bonds or at least broaden the scope of people that first years meet. Yet, something about a randomly assigned group runs the risk of feeling like an obligation instead of a genuine, natural connection.

The residential college system, Yale’s pride and joy, was designed to create smaller, tighter communities within the larger university system, and for the most part, they succeed — the 2018 YCC Fall Survey indicated that a vast majority were “somewhat satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their residential college. But experiences are not equal across all colleges. Most first years live on Old Campus, but those assigned to Silliman, Timothy Dwight and the newer colleges, Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray, move directly into their residential colleges starting their first year. Most feel ambivalent about this; on one hand, there are more opportunities to bond with their own college community and interact with upper-level students, but on the other hand, some first years feel isolated from their peers on Old Campus and left out of the traditional Yale experience.

Tiffany Ng ’22 describes her experience in Benjamin Franklin as tightknit, but only within her own college. “Is it bad to make friends out of convenience instead of going out of my way to make friends with people on Old Campus?” she wondered. “Because our dining hall is so close in our college we always just walk past each other and say hi, sometimes we sit next to each other, and then start to become a group. It’s just the sheer convenience.”

Similarly torn, Kofi Ansong ’21 views the role of residential colleges in forming social circles as a hit or miss, generally. “The structure from your residential colleges definitely helps you find a squad — but if that just doesn’t happen, it can get hard,” Ansong said.

Yale prides itself on its strong sense of community compared to schools such as Harvard or the University of Pennsylvania, which are perceived to be more competitive and preprofessional. However, the urgency to network and build strong connections within just four years is still noticeably present at Yale, often conflating friendship with network or utility. First-generation and low-income students who arrived on campus with little to no connections may feel especially disadvantaged. This culture can prime an environment of a toxic social scene, as bluntly illustrated by this post on Overheard at Yale: “Sometimes I feel really lonely, but then I go to a networking session for an investment bank and remember that money can buy happiness.”

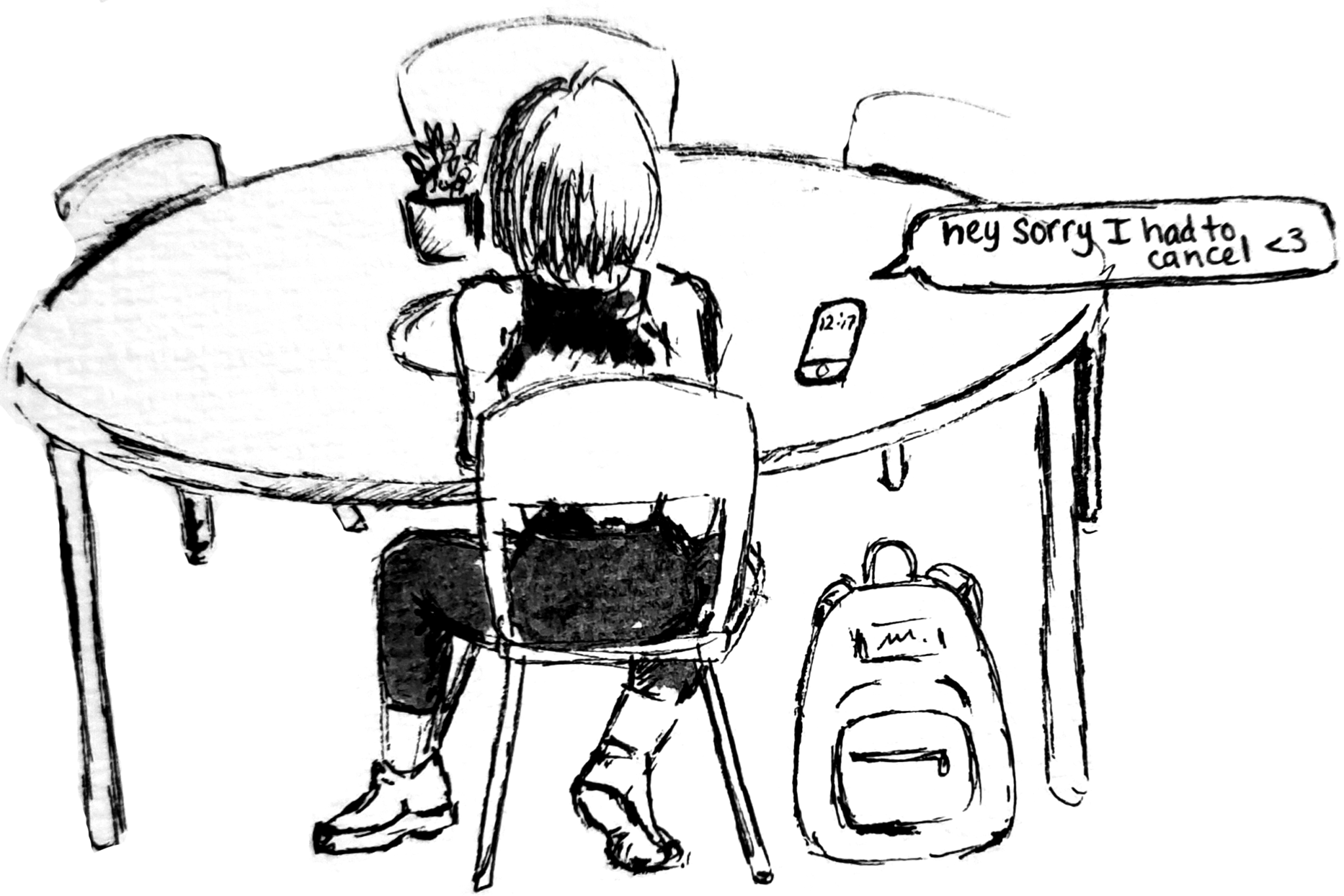

This superficial aspect of friendships in college is neither new nor unique to Yale — all students have busy schedules and varying commitments. “We should grab a meal some time!” has become a phrase to be laughed at for its utter meaninglessness, even though the slightest bit of persistence from either party could make it a reality. As Isabella Li ’22 explains, “It’s easy to meet a lot of people but it’s hard to actually get close to them because everyone’s so busy, so you have to make an active effort. And FOMO is a big thing.”

FOMO, or fear of missing out, is a counterproductive mindset that is unfortunately difficult to shake. Sufferers of FOMO are not only unavoidably missing out on what they’re worried about, but they also are not fully appreciating what they are experiencing at the moment. FOMO is ostensibly the worst on social media, of course, where nonstop streams of snaps and stories are constant reminders that everyone else is out there living their best lives — or so it would seem.

Lucy Minden ’22 described how misleading glorified, curated social media can be. “A lot of it has to do with seeing pictures online, of other people and their friends and parties that they weren’t invited to, that makes [people] feel that they’re not in the loop,” Minden said. “Whether or not those people were actually having so much fun at college isn’t really the point, but it’s about what you see. You don’t really see people grinding away, doing their work. What you see is the opposite.”

Caught in the “grind” of academic and extracurricular commitments, some students may even feel isolated by their own interests. Ansong explains that at Yale, “it’s easy to feel lonely because everyone is always busy with things that are personal to them; activities that you may be into often aren’t the same as your suitemates or residential college classmates.”

Yale is well aware of this problem of loneliness, and has implemented various measures to offer assistance. First years are notified of resources, from hotlines to counseling, available to them on campus. Walden Peer Counseling, for example, offers anonymous counseling through office walk-ins and a hotline that operates late at night. Of course, they certainly are beneficial measures and it is commendable for students to volunteer their time to counseling their peers. However, the very nature of loneliness and depression may include the inability to reach out and seek help. Perhaps, resources are not being utilized to their potential because they expect students to reach out first. For those who are already feeling lonely and vulnerable, it can be unbearably difficult to pluck up the courage to sit in front of two complete strangers, whose job is to listen to them, and speak their minds openly and truthfully. It could never be the same as confiding in a close friend, or feel as genuine with the clinical distance.

The fear of being lonely is real, but it should not become a fear of being alone. For some inexplicable reason, there seems to be a shameful, even sad, stigma about eating alone in the dining hall, going to dances alone, surviving cuffing season alone. But being alone is not the problem; in fact, it is often a healthy mental break. It may help to try to fall in love with solitude, and be at peace with silence.

Yale students who feel loneliness are far from alone. There exists a one-of-a-kind web of incredible individuals that everyone is a part of at Yale, and it takes time to truly appreciate it. In 2012, Marina Keegan ’12 published “The Opposite of Loneliness,” a viral essay for a special commencement issue of the Yale Daily News, recounting the colorful range of cherished memories and lasting regrets she had experienced at Yale. The essay’s essence can be captured in a single line: “We don’t have a word for the opposite of loneliness, but if we did, I’d say that’s how I feel at Yale.” Keegan died in a car accident shortly after graduating and writing her heartbreakingly optimistic essay. She was 22.

Not everyone at Yale can feel the same way. But at any given time, there lies the possibility, the unknown future, what Keegan called an “immense and indefinable potential energy,” that could change lives overnight and make loneliness feel like a distant memory.

“We’re so young. We’re so young,” Keegan had realized. “We have so much time.”

Ashley Fan | ashley.fan@yale.edu .

Brandon Liu | brandon.liu@yale.edu .