I.

In a home video from 1998, my mother coos, “Kyung Mi ya — aegoo? I love you.” She sneaks her index finger into my grip to gently shake my hand. It’s as if she’s been waiting for this moment, the day I became an extension of her body, when love for others no longer felt like a choice. As a fetus, I gulped from our shared umbilical cord. I fed off what she ate, swooshed with her every move, exulted in our joint existence. When the cord was cut, our nine-month union fused itself into its worldly form, an invisible thread securing our bond, jeong.

II.

Jeong is a Korean word I’ve come to accept has no English equivalent. It’s a connection between two people, a group of people and even between a person and an object, like a book, a house or a favorite stuffed animal. Korean-English dictionaries struggle to capture its ambiguous nuance: compassion, attachment, affection and heart. But none of these words, not even all of them combined, could truly encompass the amorphous nature of jeong: A kind of love that can’t be helped, the ultimate pre-existing condition.

In Korean, we say jeong dul da, which means jeong permeates, seeps in, saturates. I imagine jeong spreading like ink in water. It is an experience that sits on the periphery of the heart, outside of the self, surrounding you like a thin veil or a shroud of smoke — a connection that just is.

Jeong is embedded into the structure of our language. We use plural possessive pronouns in singular possessive contexts; there is no “I” in a culture stained with jeong. Mothers call their children oori aegi, “our” baby instead of “my” baby, while “my” mother becomes oori umma, meaning “our” mother.

I like to imagine that my introduction to jeong began in my mother’s arms. The warmth of her postnatal jeong infused itself within me, seeping into the membranes of my heart the way Korean blood runs through my veins. I entered the world with this embryonic understanding of jeong, ever growing, ever expanding.

III.

The first time I had to explain the concept of jeong was in third grade during lunch recess. Having hopped off the plane just a few months before, I was a natural outsider, the F.O.B. Asian who may or may not be mute — has anyone tried talking to her? I sat alone under a gingko tree and opened my lunch box. Cafeteria Jell-O and tater-tots dripping with grease appalled my Korean mother; how could the Americans feed this to their kids? I pulled out a sandwich bag of rice crackers and mangos, sticky from the heat of summer-turned-school-year, my first year in America.

I was opening my bag of meticulously portioned snacks when I noticed a girl staring at me. I smiled. What else was I supposed to do? She said something in English that I couldn’t understand, so I reached out my hand to offer her a piece of mango. She looked confused. She stared at my mango and then back at me, as if to say, Wait, really? We had never spoken before, and I wouldn’t have been able if I tried. She sat down next to me and took my slice of mango, muttered something in English with wide, expectant eyes.

I couldn’t quite place it in the moment, but jeong to an outcast on the third-grade playground was a piece of dried mango and the friendship it sparked. I thanked my mom for double portions, for the wisdom of her foresight, for inviting this stranger into the kimchi-stained world of our lunchbox.

IV.

I once read about a foreigner who compared the waft of pine-scented air freshener in a Seoul taxi as jeong. It caught me off guard. Could jeong be a scent in unfamiliar landscapes? Before he could recite the traveler’s Korean he had rehearsed on the plane, the driver turned around to greet him in stub-tongued English: Welcome to Korea.

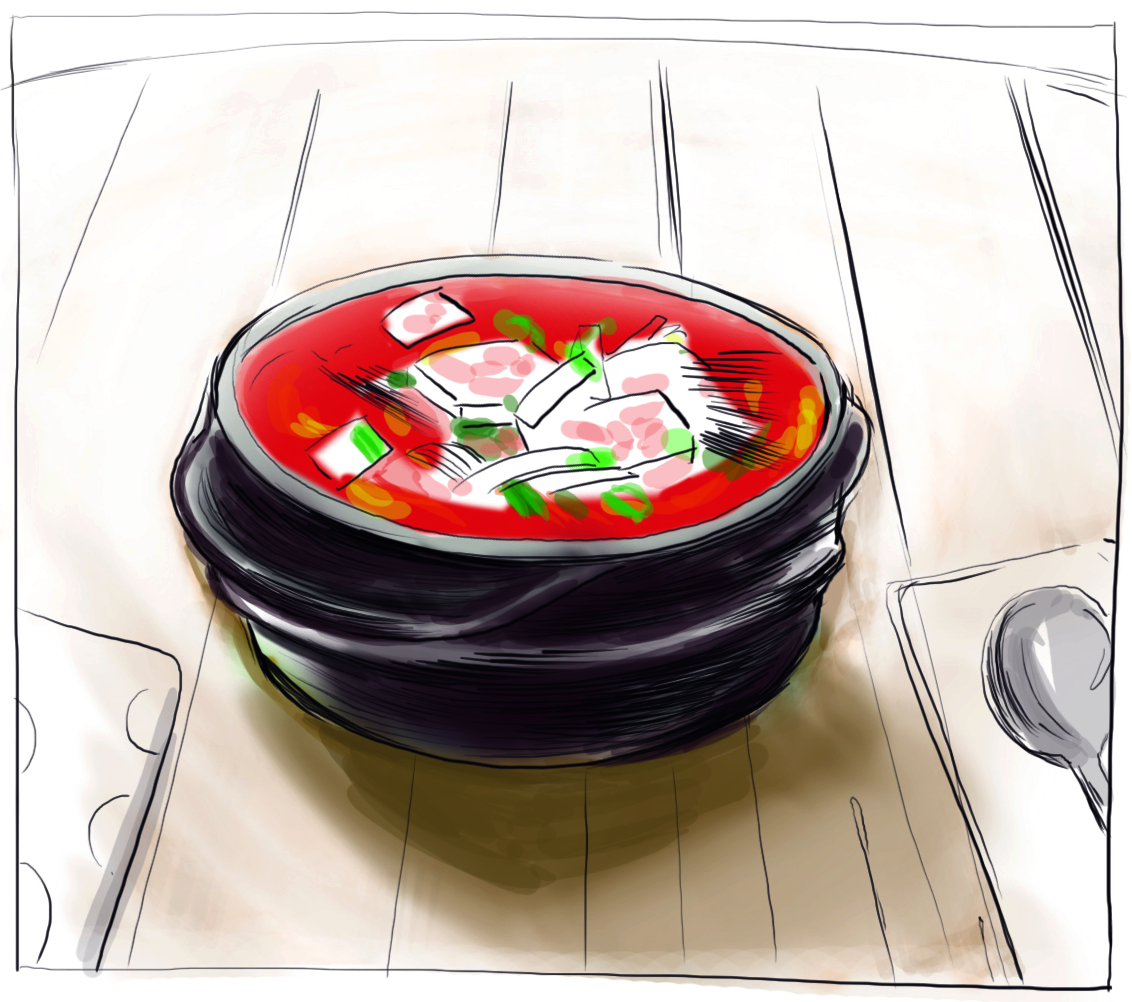

Jeong weaves itself into the fabric of Korean identity, transcending the round syllables of the Anglophone world. It drifts through Dongdaemun, the East Gate Market, where the commotion of a good deal fills the streets. Ggak ah ju seh yo, you’ll say. “Please lower the price.” The seller will refuse to budge, only to sneak a few extra peaches into your bag. Vendors sprinkle sea-salt jeong over their morning catch, and hunchbacked grandmas sell namul in red plastic baskets of jeong: assorted spring greens, herbs and mushrooms. Jeong floats from a steaming pot of jjigae that an ajumma serves at a restaurant, generously packed into bottomless bowls of side dishes, free of charge. It is unconditional giving, the unassuming grin of a taxi driver or even a little added salt to keep the fish fresh.

Long-married couples bicker like stray cats, but their jeong binds them into loveable idiosyncrasies, tolerable bedtime snoring and bellies that only grow with time. Jeong is an expression of loyalty, irrational devotion, the battling of chopsticks for the last piece of mandoo and the warmth of a mother’s hand rubbing sore gluttonous bellies. At times, it is an unspectacular feeling. It is a silent and gentle affection, humble yet unwavering through self-sacrifice.

V.

My dad began driving a cab a few years after our move to America. Every night, he’d come home to present the day’s earnings, a wrinkled sum folded in half from the weight of his seated body. On the nights he brought home at least 200 dollars, my mother delighted. She licked her thumbs to count the bills, beginning with the largest, sometimes a fifty, and ending in the singles piling up to a whole 20 dollars.

“Only two hundred?” she’d tease, tapping to straighten the stack on the kitchen counter.

He chortled, “Two hundred not enough for you?” and wrapped his arms around her from the back, an uninvited show of affection I suspect she loved.

Two hundred dollars was never enough. Never enough to stock the fridge for lunch, to pay the cable before it cut out, never enough to send in the checks for our monthly tuition plan — a heap of unopened notices ignored in the mailbox. Two hundred dollars barely crossed the threshold of my mother’s heart, giving her a breather just long enough to fall asleep at night. Dad came home long after nightfall and scribbled his earnings onto our free church calendar. Mom saw the numbers and sighed; at the end of month, his efforts always fell short.

Sometimes she found him napping on the couch and scowled, “Aren’t you supposed to be driving right now?” He would roll over into his uniform folded neatly beside him and retort in a flu-stricken voice, “Don’t I ever get a day off?” to which she replied, “Ya, jeong ddul uh jin da.” My jeong for you is dropping.

It’s been 20 years since the night of my parents’ honeymoon, 19 since the birth of their first child and 10 since our move to Hawaii. When luck runs its course and patience runs out, I’d imagine that love may collapse. But I know better than to charge love with the task of lifelong partnership; it’s jeong that keeps them attached.

She packs it every morning into his lunchbox set silently on the table and picks it out at Macy’s when his shoes are falling apart. The way that she chuckles and frees herself from his back hugs, the way that she mutters, “Gross, you stink,” proves to me that jeong exists far beyond the constraints of their worn-out marriage.

When my mother complains, “Ya, Jeong ddul uh jin da,” she says it with the knowledge that jeong cannot be dropped. It’s a phrase we coat with sarcasm before muttering under our breaths, a silent appreciation of the permanence of jeong.

VI.

The last time I explained the concept of jeong was to a boy I’d been seeing. We were staring at the ceiling, snug under his covers, pondering our favorite words. Opulent, effervescence, night, fastidious; I searched my mind for all my English words until I realized: Jeong is my favorite word.

“Well… there’s this Korean word,” I began to mumble. Did a translation even exist? “It’s kind of like affection, kinship and empathy. I don’t know. It’s more visual for me. I’ve always imagined it like a thread connecting people. Like everyone walks around with jeong attached to their bodies.”

I felt a hidden intention in my rambling, an urge to protect the ambiguity of jeong, to allow the uncertainty of its translations. Perhaps there’s something sacred about hazy definitions.

“Jeong… That’s cool,” he replied.

I nodded, nestling into his arms. He pronounced the word correctly, almost perfectly. I remember thinking that we had probably grown in jeong, me and this boy who lacked the words to describe our love. I fell asleep in his arms, wrapped in the warmth securing our bond, jeong.

Kyung Mi Lee | kyungmi.lee@yale.edu .