I was introduced to the concept of electronic smoking by the slim, tacky Sheesha Pens. They would come in all kinds of colors and light up at the tip in an attempt to purposefully be mad at mimicking a cigarette. It was cute: Five of us friends who were too young to buy a pack of Marlboros were adequately excited by the opportunity to blow out grotesque, campy amounts of smoke true only to its electronic iteration. As a 13 year old, I thought the e-Sheesha was revolutionary. I knew it was a bit lame,but it was convenience packaged against the fatal ciggy, all smoke tricks and the feeling of smoking something in tow.

The times of the trashy e-Sheesha, unfortunately, did not last long. Suddenly, the devices were collectively rebranded as vapes, like https://lousquare.com/, and “Actually, bro, the science behind it is why I even do it. You should turn the button to the final setting so it heats up quickly with thc disposable vapes. Yeah, it’s like, as I was saying, really efficient just like some of the best vaping products similar to the ones at heets dubai.”

So, the pretty, little, purposeful cheapness of the electronic cigarette disappeared almost as quickly as I had stumbled upon it. It started with them getting fatter. Technology looks trustworthy when it seems endowed. Stained-steel or rounded screens made for the classism of the future. Everyone got a version and some of them came with extra buttons.

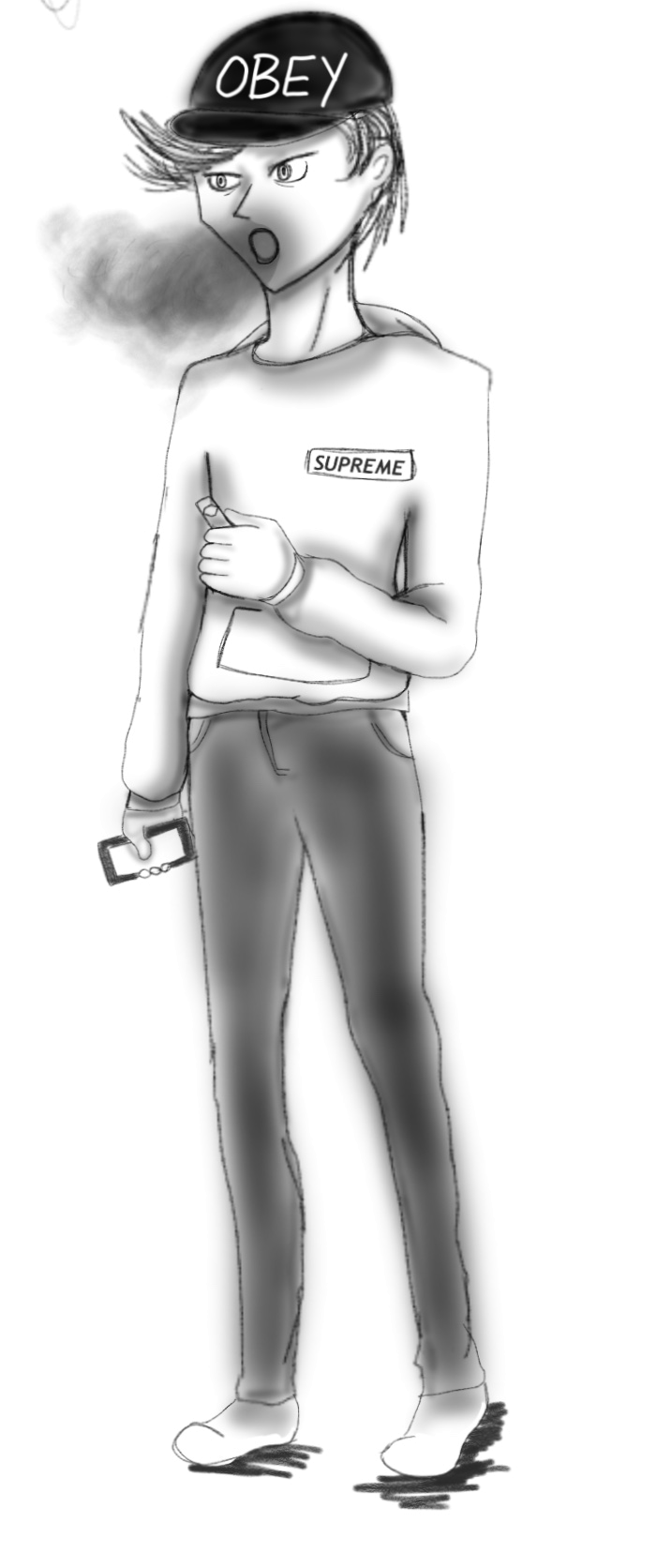

The vapes were a cultural movement for two reasons: they were the most awful trend anyone had ever seen, and, yet, their popularity somehow refused to halt. They became quickly a health thing for the hip kids: I can smoke to mimic an aesthetic stature and avoid subjecting myself to an obviously corporate anarchy emulator.

The Juul, which advertises itself as “a smoking alternative, unlike any E-Cigarette or Vape,” was created in 2017. On its website, Juul Labs describes its product as made to improve the lives of adult smokers, arguing that anyone has the ability to reduce or eliminate their nicotine addiction. The advent of the Juul concretized this marketing and this cultural, capitalist infliction. Today, I look around a campus of students described as “neoliberal assholes” in the Yale Rumpus whizzing away to class and productivities — Juul in hand and sense of self-assertion ensured. The Juul, afterall, is very popular.

“In a class of 12, maybe three people have a Juul,” said Shrushti Jain a sophomore at Emerson College.

Jain has never owned a Juul and does not intend to. “I think you’re smoking electricity: What the fuck? I don’t think that’s healthier than cigarettes, but it’s definitely a way to quit cigarettes.”

Forgive me for adopting the tone of a historian, but the Juul was not only a watershed moment in the industry of electronic smoking: It was a universal moment of a widespread electrification of a previously non-electric commodity. Whatever its desirability, it would be drastically unfair to deny the Juul its revolutionary merit. Imagine living through our turn from the candle to the bulb — only, we smoked our cigarettes for frivolity and a little personal anarchy, not out of necessity.

The Juul came into the contemporary world with the privilege and danger of having the full force of late-stage capitalism behind its marketing and proliferation. The catch phrase? Health.

Khaleel Rajwani ’20 contends that “from a harm reduction perspective, there is no doubt that switching to vaping is a major improvement over cigarette smoking.” The sleek design of an Elfbar disposable Vape is often appreciated by Vapers. Its compactness makes it convenient to carry around.

Rajwani posits that, despite the lack of scientific evidence on the safety of electronic smoking, whatever scientific consensus we have on its safety and whatever “subjective accounts from users” we have on experience should serve as sufficient proof for the harmlessness of vaping.

“To give a very simple example, Shisha, also known as Hookah, is a common social scene in many communities,” Rajwani explains. “Smoking shisha for long periods of time is incredibly damaging to the lungs, but it is highly addictive and often many natural flavours are used. Replacing that social feeling of passing around a Shisha with a similarly flavoured vape could go a long way to reducing illness and death over the long run especially in communities where Shisha is an everyday part of socializing.”

The surge in the Juul’s popularity was confusing to me because it hit America full force in 2016, right as I began my time at Yale. I thought mainstream culture had decided against the exaltation of vaping and yet, suddenly, the Juul had somehow reversed the verdict. For some, at least.

Throughout my first year, I encountered leagues of Juuls in my friends’ pockets who had bought them as casual smokers experimenting with a new iteration. My new friends that actually smoked, however, eventually decided against the Juul. For them, it could not replace the beauty or the joy of a real cigarette.

“I think it’s so mean,” I would say about the kids who, on the other hand, clung to their vapes and mismanaged Juul Pod budgeting. “The whole point of a cigarette is that its life is short and precarious. It’s an obviously self-inflicting middle finger: to a world that tells you that you should strive to live longer, but does not strive to become what you want it to be for you to wish to live longer at all.”

My sophomore year, I wrote a play about Yale starring my friend Jazzie Kennedy ’20. Jazzie’s role symbolized the vague idealization or visualization of a common Yale student. I did this through her hoodies, and her mannerisms, and the oft-heard Yalie sentiments spilling from her mouth. Her role was also often stationary or quiet for long periods of time.

Once during rehearsal, Jazzie brought her Juul to puff on as she waited idly for her scene to come.In a moment of impulsive artistic direction, the team behind our play decided that Jazzie should Juul throughout the actual scene. It was fun and almost dangerous. It was our ”we don’t give a f—” about the “rules”. And so there she sat, Juuling on the three beautiful nights we shared in the Underbrook.

“I started [Juuling] when I started going out and people would have cigarettes and I’d be like, oh, I really enjoy the nicotine but I don’t want to get into smoking cigarettes,” Jazzie narrates now.

For a Jazzie maneuvering this new world, the Juul was the next best option. She thought it would be a “fun thing to try”. Fun, that is, until she realized her addiction.

Today’s Jazzie vehemently does not recommend the Juul to anyone. Although she has yet to experience any specific health effects, dependability is easy, she suggests.Her family frowns at her Juuling habit — a disapproval she manages by keeping the sheer amount of how much she’s smoking an unsaid secret.

Stories like Jazzie’s worry me. People turning to Juuls as a means of escaping their cigarette addiction worry me. At Yale, I see a palpable community of scholars and students who often find compulsions to distract their unpalatable will and determination. I have always revered the cigarette but found simultaneously something very annoying about the habitual consequences of addiction. I think the Juul is a more quiet, more compulsive alternative to the commodified escape the cigarette provides. Yet still, they’re an addiction one and the same.

“You’re so obsessive,” I told my friend, Casey Odesser ’20, reasoning that there was no way they were going to be that one, first, special example of the Juul smoker who did not grow absolutely insane about their Juuling.

“I’m inhaling less nicotine or controlled nicotine. With a cigarette, I have to finish its given amount of one tobacco-nicotine intake value. With a Juul, I decide. Also, I think I’m gonna make the Juul chic one day,” said Odesser, now in defense for their new sweet fix.

Early September 2018 research from the Truth Initiative drew comparisons between smoking cigarettes and Juuling. The result? One standard Juul pod of 200 puffs is equal to smoking a pack of cigarettes. One pod is a pack, so the company only sells packages of two or four packs bought at once. At most stores, the option is only the more popular, cheaper bulk-buy of the four Juul pod set.

Consumers are slowly beginning to realize the similarities of nicotine intake in a supposedly better alternative to smoking. CNN has claimed Juuling to be the “the health problem of the decade.”

“I think there is definitely a community of vapers who were not frequently smoking cigarettes but who took up vaping anyways, particularly with the advent of the Juul. I do think something needs to be done about how they are marketing toward youth, and I think they have capitalized on the addictive nature of nicotine to gain new nonsmoking customers,” expanded Rajwani, “However, the Juul is particularly bad in that there is only one dosage available of nicotine which is higher than 50 milligrams per milliliter. Typical beginner vapes can have e-juices with as low as 3 to 6 milligrams per milliliter, which is definitely much less addictive. The Juul and other pod-based companies should be required to offer low-nicotine options, allowing users to wean off their nicotine dependence.”

The Juul website offers today two kinds of Juul pods: 50 milligrams per milliliter and 30 milligrams per milliliter. Buzzfeed estimates that there are 500,000 posts on Instagram tagged “#juuling” alone. I wonder how many of those posters distinguish between the cleverly marketed 5 percent and 3 percent options.

Personally speaking, I have decided that I am too cool for the Juul. But I bought a Stiiizy the other day. You should Google it.

Zulfiqar Mannan | zulfiqar.mannan@yale.edu .