If in 1718 a small college in Connecticut, hadn’t accepted £562.12 (over $100,000 given modern inflation) in goods, 417 books and a portrait and coat of arms of King George I from the wealthy textile merchant, Elihu Yale, this university might still be known as the Collegiate School. While we do not explicitly venerate our namesake as an individual, his presence lingers in the four letters emblazoned on blue placards, T-shirts and baseball caps across campus. To say that Elihu Yale’s legacy has informed the school’s culture for the past 300 years may be an exaggeration, but undeniably, the elite university’s paragon of success is the entrepreneurial white male donor.

The significance, both subtle and overt, of a name is well-known to the Yale community. Moving daily through Yale’s campus, it’s nearly impossible not to feel a yawning gap between our progressive student body and the institutions of tradition that surround us. This school was not created for the multicultural, dynamic set of learners it now houses. Campus tours often ask prospective students to consider whether they can envision themselves here as part of a diverse, dynamic student body. But the question is whether they see themselves represented “here,” against the University’s brick and mortar foundations.

The narrative lived by Yale students every day is one of male achievement, or rather recognition of male achievement. There are comparatively few representations of women and nonmale accomplishments. For men, it is a city of mirrors, while for everyone else, it’s more of fun house that requires mental labor to reconcile one’s sense of self with the distortion reflected back.

We wondered what it would be like to erase the masculine facades and in these blank spaces choose to celebrate and recognize the achievement of women.

“Welcome young, bright-eyed prospective students to Collegiate University! As we embark on our tour we encourage you to look to our buildings and boulevards, our reading rooms and residential colleges and question not only whether you could see yourself here, but whether you see yourself represented here.

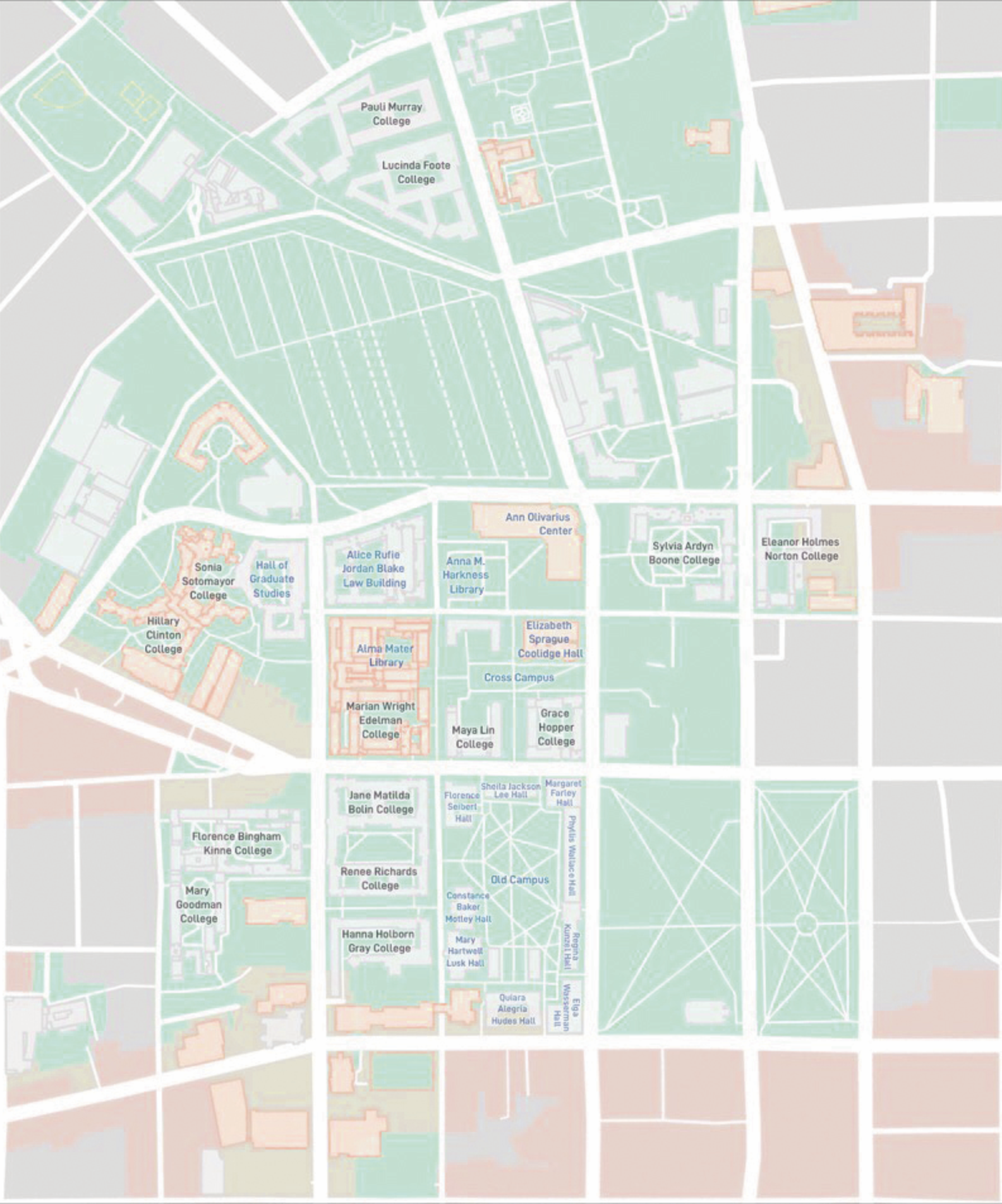

“Let’s begin at Mary Goodman College. In 1872 Mary Goodman, a former slave and owner of a laundry service, bequeathed her savings to the Yale Divinity School to establish a scholarship fund for black divinity students. This was the University’s first gift by a person of color and served as a catalyst of social change within the Div School. Admitting more students of color, the Div School became committed to training its students to be leaders in communities facing systemic inequities and growing wealth gaps. Today, the scholarship in her name persists, providing education to black students all thanks to Mary Goodman’s donation 146 years ago.

“Just north of Goodman is Florence Bingham Kinne College. When Kinne was hired to teach in the pathology department in 1905, she was the first female instructor in the department, with the title assistant in instruction. Yale School of Medicine did not begin admitting women until 1916, so Bingham Kinne would have been the only woman in nearly every space she entered during her time at Yale.

“Here on the left we have Clinton and Sotomayor colleges — very popular for aspiring law students. Then we’ll be passing the Alice Rufie Jordan Blake Law Building. Jordan Blake was the first woman to graduate from a graduate school with a law degree in 1885, before the law school officially began admitting women. Jordan Blake’s impressive intellect and ability to spot a loophole (the school depended on tradition rather than an explicit written policy to exclude women) earned her a place in the program.

“We’re now coming around to Sylvia Ardyn Boone College, named for the first black woman to be granted tenure in 1989. She was an art historian specializing in female imagery in African art and she taught at a time when only a handful of the students were women, even fewer women of color. Her seminal course “The Black Woman” and her founding of the Chubb Fellowship contributed to the development of community and recognition for students and scholars of color at Yale.

“Circling back to the middle of campus, we’ll pass Renée Richards College. Richards is an opthalmologist and former professional tennis player. She won a landmark Supreme Court case challenging a transphobic policy instituted by the U.S. Open stipulating that female players undergo genetic screening before being admitted. This policy was instituted after Richards announced her transition. Richards’s success in court ultimately allowed her to compete in the Open and the policy was denounced as discriminatory.

“Here at the center of campus and the end of our tour is the Alma Mater Library. Pulling open two sets of wooden double doors and gazing down the nave, every visitor confronts the painting “Alma Mater” depicting the female allegory of the Alma Mater. She represents the spirit of scholarship and academic pursuit here. It is often the case that visual representations of women are limited to the allegorical and symbolic, standing in celebration of the achievements of men, while actual women appear less. Alma Mater serves as a repository of knowledge and information as a physical space, but also as a body to house the memories of other great women whose names have been forgotten but whose work has marked this campus, city, or world in some way.”

Inequity between men and women in academic and professional spheres is more than just symbolic. For instance, of all the student loan debt incurred by students nationally, women bear two-thirds of the burden — the result of lesser pay for equal work and fewer women being hired into prestigious, higher-paying positions. While rebranding an entire campus for the empowerment of women would be highly impractical and, in fact, not the solution (though it sounds like a utopia), increased representation could be one element of a cultural shift needed to ensure that this is a school ready to nurture the ambitions of anyone regardless of gender, sexuality, race or religion.