Many afternoons as a child, when fragments of the sun splintered through my window pane, I would feel compelled to go outside and sit on the broken wooden swing in our backyard. I would take a sheet of paper and a pen with me so I could scribble down what I saw of the trees, their broken silhouettes, how they could not attain the sky.

I’d feel my weight push into the swing, and sometimes I could hear when the swing broke where it couldn’t handle the pressure. Pieces of the swing would peel off like ruptured old skin. I’d hold the slices of wood in my hands, press my palms together as if in prayer and let the jagged edges poke into my skin. I have always wanted to break into things, and for a while many thought this impulse was destructive. Once, in elementary school, my teacher yelled at me in front of the whole class for drawing on my desk, but I hadn’t even realized I was drawing. My cheeks flushed red. What I was trying to do, if I recall correctly, was to carve my pencil into the wood, to see if I might be able to crack its surface.

Sometimes, when I dream at night, I envision the swing breaking into clean fragments, and the splintered wood causes a splinter to emerge in my finger, and the splinter, once opened, reveals a world that I have not seen. In this world, blue visions float, visions of my mother as a teenager in India, leafing through blank pages of a drawing book, and my father at his first job in Bangalore, stuttering nervously. They dissolve on my tongue and I can taste the images, however briefly.

***

In preschool, during recess, I’d sit on the playground’s looming structures — usually either the slide or the jungle gym — and watch all of my classmates playing, coming together and breaking apart like molecules. I’d hunger at once to be part of the chaos and removed from it. One day, my teacher’s assistant, Ingrid, came and sat next to me on the jungle gym and asked how I was doing. I knew she could tell I hadn’t made many friends in school, and she wanted to check in on me. I told her how my name was pronounced. It’s May-guh-nah, I said, like the month of May. She smiled, and during every recess for the rest of the year, we discussed oranges and Chapstick and names, her strange uncle and the birthmark on her knee shaped like Alaska. Ingrid and I became best friends.

***

There is something about trees and their potential that frightens me, and perhaps this is why I was afraid of climbing my grandfather’s guava tree years ago. My sister and cousins all climbed the tree and marveled at the view of the sky from above, coconuts falling onto the ground and the rumble of the clouds, coalescing into a music that I couldn’t hear from below. I watched them, an ant on the ground, wanting so badly to climb too, to join them in their vision of the world.

***

Once, I saw a cow dying on the streets of India, in the light and noise of the bustling cars. Before it died, it craned its neck upwards toward the sun. The blood spurted out onto the streets, painting the concrete red. The process of dying seemed to me almost mechanical, a process akin to the emptying of batteries, the loss of a power source. I watched, my eyes glued to the performance, as the cars swerved around the dying cow, but I could not feel anything thumping in my chest; it seemed there was only a stone. I wanted to envelop the cow’s body, to lie in pain on the streets, so that I could understand. The cow pulsed, its black and white skin peeling off its body like a sticker. It was not the sight of death that pained me but the cow’s solitude, how the cars and people scurried around, surrounding the cow and yet leaving it utterly alone.

***

Last Friday, I was walking up the stairs to my suite when I saw a stream of light flooding out of someone’s common room. The door was left ajar. I walked in to find one of my friends sitting around a table with several other students, the majority of whom I didn’t know. Without thinking, I sat down at the table, and my friend poured me a glass of wine, and I began to sip at it, slowly. I looked around the room, at unknown faces, and each face seemed composed in a precise way, an organization I could not break. An acquaintance of mine started playing guitar, and then one of the students I didn’t know asked about everyone’s first memory. I listened to the stories as they tumbled from mouths, one after another, and I knew that soon it would be my turn. My first memory. My mind flickered back to Ingrid and the cow dying on the streets, my mother and my father and how I dreamed often of their lives, the parts I couldn’t see.

I kept listening to others’ stories and the room fell into a quiet chaos. I felt at that moment that I could grasp the machinery of the world, for entropy seemed perfectly understandable: It was something like being human, the ways in which we come to see each other, suddenly, unraveling.

In the “Great Gatsby,” one of my favorite books, Nick Carraway stands at the edge of a boisterous party and presses his face to the cold window. Below, he sees a passerby who looks up, and Nick realizes that he’s the passerby, too, looking up and wondering, within and without. I glanced around the room, at my friend, who hours before had been a stranger, and I saw that his eyes had the same brown hue as my sister’s. Everyone is an iteration of someone else, and then we are not so alone. Maybe love is the opposite of tracing a body and avoiding its mass; perhaps it’s the enveloping of someone else’s skin.

***

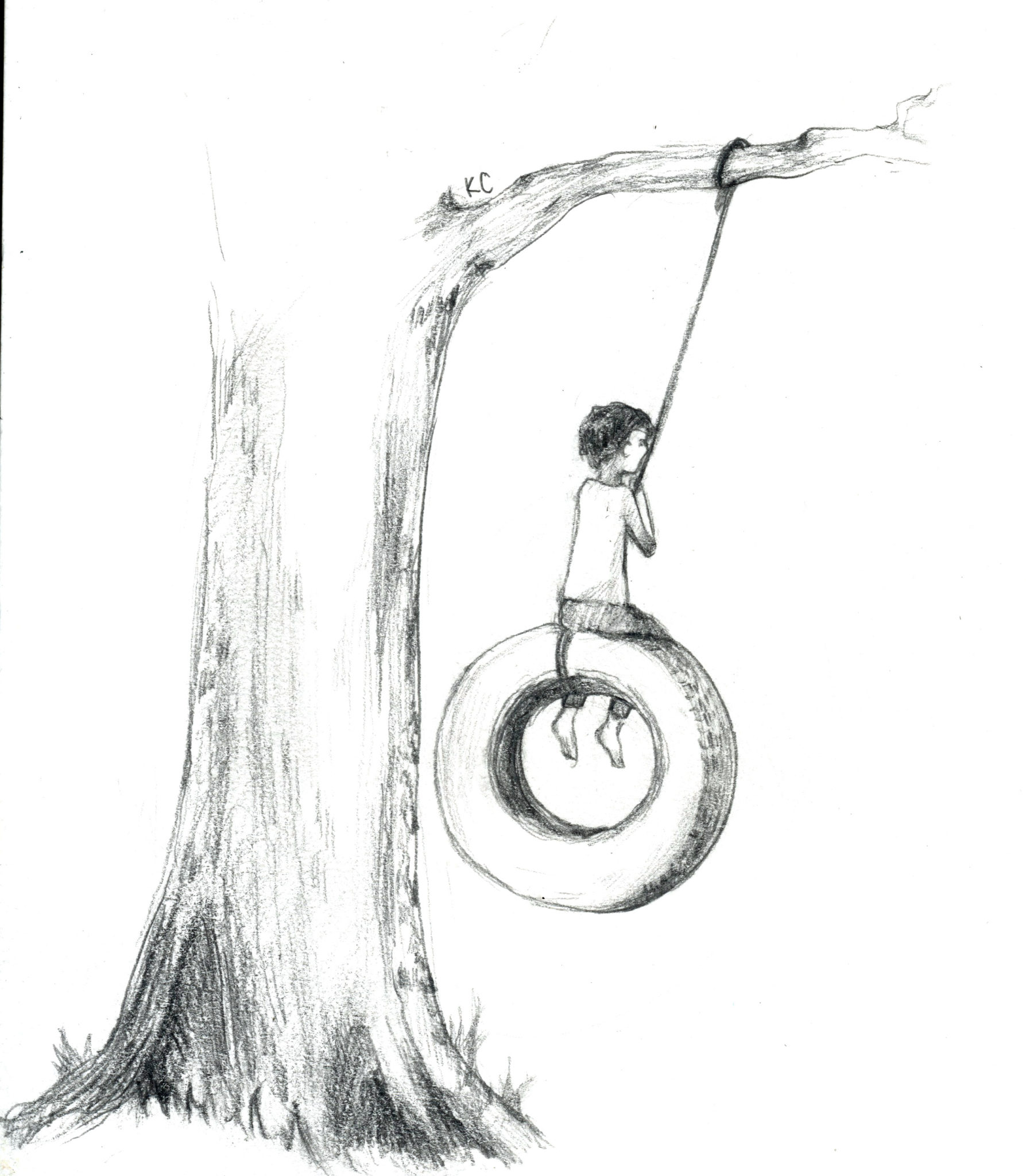

My first vivid memory is of falling. It was the first time I ever rode a tire swing. I got caught up in the fury of spinning, and then I spun too hard and fell head first onto the ground. The bark chips scraped my forehead. It hurt. My second memory is eating chicken with my father and sister at our dining table and clawing with my fork at the tendrils of meat.

The other day after class, I didn’t know where to go so I meandered over to the ledge in front of Sterling Memorial Library. The sky was as dark as a glass of red wine, and I felt unbearably cold. I remembered the guava tree. When I finally did climb it, I experienced a sense of elation I hadn’t felt before. I thought I could see the entire world, every iteration of myself, and that I could taste the pink guava air, hot and alive. I could see the coconuts falling from the trees, thudding on the ground, and, in my mind, like dominoes, the trees toppled over and came apart, and I could hear my third grade desk breaking, the swing breaking, my head falling on the bark chips, the barriers between myself and those around me deteriorating.

I looked out onto Cross Campus and thought of all the people whose insides pulsed with darkness, the iterations of others’ joy and pain that I could not swallow or understand. The sky above hung ominously, and I squinted hard at it, so hard I thought I could see something unraveling at the dark center like tendrils of meat; for a moment the picture came undone, and I thought I could see inside.

Meghana Mysore | meghana.mysore@yale.edu