Whether it is transportation to Canada, a menu for a Kentucky Derby party or a schedule for completing all the readings I was supposed to finish over the weekend in a day, I have become an expert at making plans. Through trial and error, I have learned to calculate travel times and anticipate running out of sweet tea. It seems as though there is nothing a little forethought and a willingness to multitask cannot solve.

But there is one plan I haven’t been able to make, and it has haunted me ever since I stumbled upon an excerpt from Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day.”

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?”

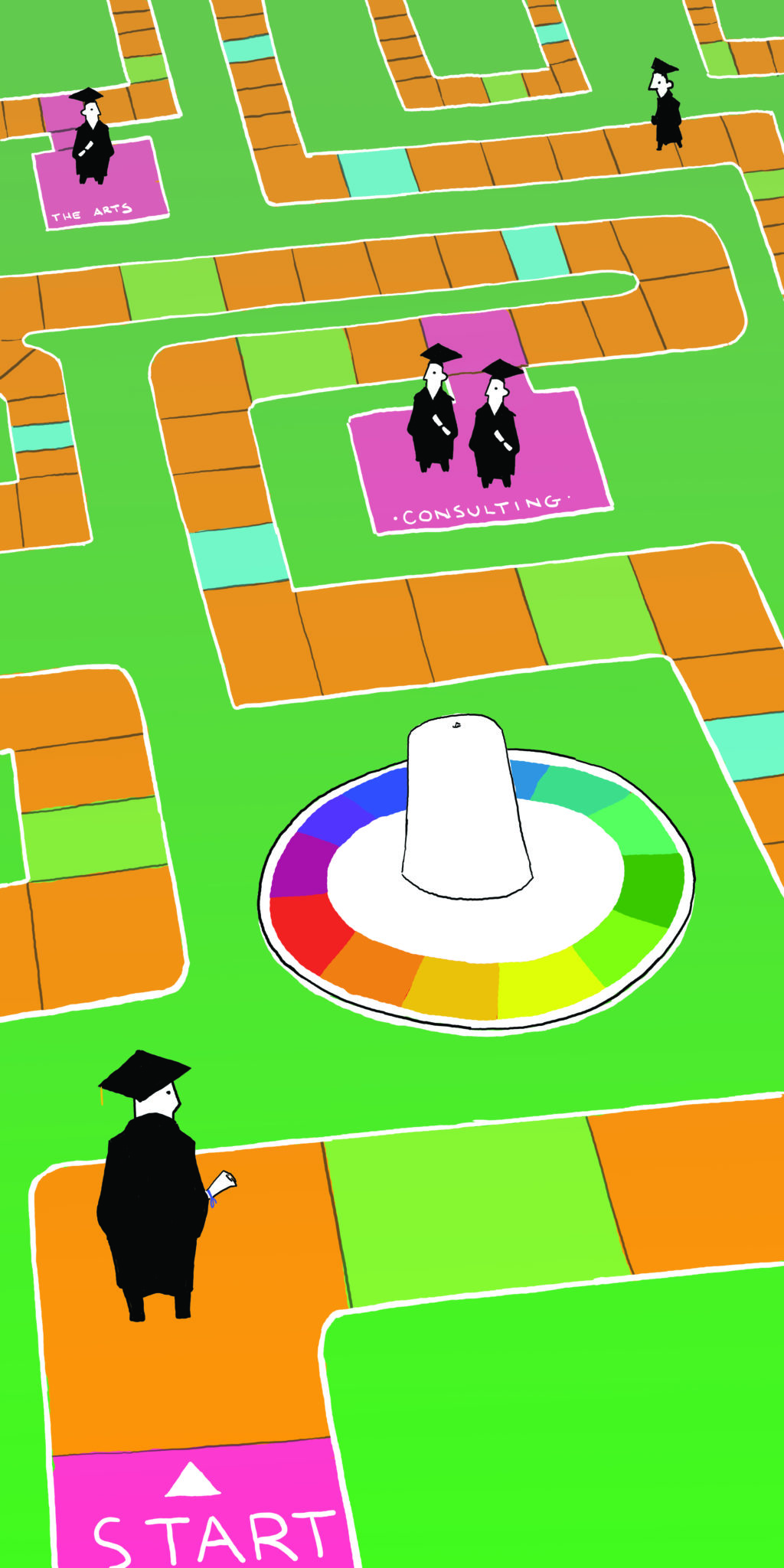

Most Yalies are adept at making plans. We are efficient at applying to internships, jobs and fellowships. We are experienced at reciting our intended path to tenure or residency or publication. But rarely do we openly discuss why we are compelled to choose the lives that we do.

I sat down with Yalies, current students and recent graduates alike, to discuss their views on the intersection of personal and professional lives, their motivations for pursuing their chosen paths and their hopes for themselves and the future.

One of the biggest questions Yalies, and college graduates in general, will face is what lifestyle they will seek after they graduate and choose a profession. Many jobs or research projects require enormous time commitments. According to the International Labor Organization, Americans work hundreds of hours more per year than their Japanese, British and French counterparts. It can often feel as though we are driven to pursue excellence in one particular career because of our own passions, ambitions, and internal or external expectations.

“Our minds and the culture at Yale really does push one side of this — the salary or career side — more than the family or well-being side,” psychology professor and Silliman Head of College Laurie Santos told me.

In regard to the best life they can imagine for themselves, some students embraced immersion in their interests while others elected to put their personal life first.

“My ideal career for the record would be something that gave me a lot of free time to spend with my family or traveling or something like that,” said Bryce Crawford ’20. “I think the best life I can imagine for myself would probably be married with time to cook good food, time to take care of a pet and have kids. … People come to Yale with big dreams, and I think that’s good, but I wouldn’t want me pursuing excellence in my career to come at the expense of family time.”

Many Yalies expressed a desire to have both professional excellence and family by striking a balance between the demands of their careers and personal lives.

“If I were able to support myself and family while essentially pursuing developing my understanding of the music that I love and developing my ability to imitate it and expand upon it, that would be the ideal career,” recent graduate Daniel Leibovic ’17 said. Leibovic had spent time working for a technology firm before deciding to pursue his passion of music. “I was definitely more financially motivated before [but] now intellectual fulfillment is the main motivator rather than like financial or conventional status driven accomplishment.”

Santos recognizes that financially driven motivations can be difficult to ignore: “I think there’s a culture here of worrying more about certain measures of success, like salary and a job with name recognition, at the expense of other kinds of success, like being happy and leading a meaningful life. In my PSYC 157 ‘Psychology and the Good Life class,’ I try to emphasize that salary and accolades don’t make us as happy as we often think.”

Surprisingly, or perhaps not for some, in discussions about their future, the Yalies I interviewed spoke more about personal fulfillment than finances. Yalies like Sonia Ruiz ’19, the illustration editor for the Yale Daily News, are searching for financial stability, but financial benefits serve only to support a fulfilling life that includes achieving professional goals and time for personal life and service to others.

“Long term, I’m looking for overall fulfillment where I can connect the passions that I have and the excitements I have developed over my time at Yale and before Yale into something where I can make a tangible and exciting and awesome impact in a field that I enjoy,” said Max Sauberman ’18, who intends to pursue management consulting after graduation. “I want access to the community and the school resources and town resources I grew up in. That’s important to me. But at the same time, what’s also important to me is that I can do with my life what I want to be doing with it regardless of the kind of lifestyle that I want to live. It’s a natural tug of war that I feel like most Yale students will have until they graduate.”

Michelle Tong ’21, a first year in Pauli Murray who wishes to work in urban design, agreed that financial security does not eclipse “being happy with yourself and what you’ve contributed to the world” in importance. It is not enough to have a steady salary — for Tong, a job needs to be fulfilling “to the point where I think I’m contributing in some way to help society.”

While Yale is typically characterized as a singular bastion of privilege, in reality attending any college, Ivy League–certified or not, places you with the elite: only 6.7 percent of the world’s population holds college degrees. Students at Yale are exposed to extraordinary professors, magisterial texts and abundant resources. As we sip chai at a college tea with a pioneer in a field or listen to lecturers with international accolades, it is difficult not to be keenly aware of the plethora of opportunities before us. Some people argue that because we have received this elite education, we are morally obligated to use our talents and skills to help those who were not given these opportunities. Although Santos agreed that Yalies do have an obligation to use their education for something important, she argued that fulfilling that obligation does not preclude pursuing one’s passions: “As long as you’re doing something that you love, something which uses your unique skills, there’s nothing irresponsible about it,” Santos said.

But while some other Yalies and graduates agree that people have a duty to try to affect some good in the world, they question that a Yale education has anything to do with moral duty.

“I wouldn’t say that as Yale students we have an obligation. I would say as people who live on this planet earth, we all have an obligation. I don’t think the mentality that because we go to Yale we should do ‘this,’” Tong said. “Because we are people who coexist with other people, we have a duty to make this world a better place for everyone to live together and not necessarily just to make our own lives better.”

Alison Levosky, who graduated from Yale in 2017 and now studies musical education at Columbia University, agreed that the desire to serve her community does not stem from a higher educational imperative: “For me, it’s more about, God has given me X, Y and Z, so I want to give that back to the people around me, wherever I end up in my life.” Similarly, Stephen Williams-Ortega ’20, wants to use his skill at writing to become a leader or community fixture to try to take the things that have been given to him and reflect them back to people who have not had the same opportunities.

Stefani Kuo ’17 also finds fault with the premise that Yalies have a moral responsibility simply because they went to an elite school. Kuo graduated in 2017 and now lives in New York City as an actress and playwright. She worked for a time in a restaurant with many people who did not attend college, and after a time, she asked herself, “Why do you have this superiority complex about your higher education because it doesn’t make you a smarter person, it doesn’t make you a better person, it doesn’t make you any of those things — these people have aspirations, too.” Kuo feels an obligation to make art that challenges both herself and the world. But that’s separate from the Yale name on her degree, because it would be “such an elitist thing to be like, ‘I went to Yale and therefore I do a certain kind of thing and save the world.’”

Crawford similarly rejects that graduates have a moral debt to be repaid: “You don’t earn your spot here before you get here, and you don’t earn your spot here while you’re here. … You earn your place here after you leave,” he said. “That being said, it doesn’t mean that you’re obligated to do something that the world is going to see as grandiose. … Your life is still yours, and you don’t owe anybody else your life because you were admitted to a nice school. … I think deserving your education probably means in some way in the future or in your life trying to enlighten society in a positive way, and maybe that’s by being an elementary school teacher.”

Leibovic concurred that his life would be very unsatisfying if he did not try to pay forward some of the privilege he has received. However, he did not think that pursuing “the kind of detached and abstract moral good” was an adequately powerful everyday motivator. Rather, he found more meaning in pursuing his own passions directly.

“Some people, I think, may be able to be motivated by that idea [that] their overall trajectory in life is approaching some kind of justice,” he said, but for him personally, he experienced a “gravitational pull” toward exploring music, and it was “a far greater pull to my everyday motivations and energies then the pull of ‘you need to accomplish this justice in the world.’” He felt compelled, for now, to pursue “selfishly” the passion that made him give the most of himself every day and later readdress the question of the good he is creating in the world. Upon reflection, he had realized that the best way for him personally to have a positive impact was to do what he loved, and then, with whatever financial or social wealth he gained, to do right by humanity.

Sauberman agreed that it is important to him that he meets his own needs before he can address ways to improve society but said that happiness for him is a low threshold: “After a while, if I’ve got all I need to live comfortably and happily, I’m not going to try to keep living comfortably and happily because then the returns are just so diminishing.” At that point, he’d rather employ the privilege afforded him by his Yale education to make a positive impact on society, whether through business or philanthropy or entertainment.

Often at graduation ceremonies, the commencement speaker will address the graduates as the “leaders of the future.” It is a fact of nature that the young will one day replace the old, that they will preserve the good and spark change.

“Your generation will be running things soon,” Santos said, “so I hope Yale students will go off and become true leaders when they leave this place.”

But how do students interpret leadership, and is it a mantle they seek for themselves?

During her time at Yale, Ruiz saw a cultural expectation that students will become leaders and change the world. But rather than seeing leadership as a flashy, individualistic pursuit, she thinks that trying to change the world is more like conducting research, which is an inherently gradual process. Each individual person builds on the small contributions of someone else, and over time the person makes a real difference.

“It is okay to make a small chip, just as it is okay to make a large one. It is also okay not to be the leader — long-term change is seldom about a person anyways. The future goes on for a long, long time.”

Kuo, a New York City–based playwright who is passionate about Asian American representation in theater, said she did not feel like a leader at all: “I don’t even know what a leader means really because you can be leading in totally different ways. I feel like, just for me, if I get to produce a show that is seen by people, that changes one person’s view about race or gender or about the theater, that’s enough. I don’t need to be the leader of the Asian American theater industry.”

Tong believed that everyone should “do the best they can,” but also that not everyone is “cut out to be a leader in the traditional sense.” Some people have personalities fit not for leadership roles, but other life pursuits. The speakers that employ leadership rhetoric in college commencement speeches, Tong suggested, “make it seem like everyone has to be one type of person, and I don’t think everyone has to be one type of person. They can make their own change and impact the world in their own ways without being a traditional sense of a leader.”

Everyone finds their own meaning. If there were a blueprint for a perfect life, Yale would have one major and one class — probably taught by Professor Laurie Santos.

“There’s never a moment where you ‘figure it out,’” she said. “Our lives and careers and passions are supposed to be constantly evolving, and … that means switching things up, taking unexpected paths and trying out some things that are risky.”

If your desire is happiness, seek it. If your passion is justice, fight for it.

And remember that your life is wild and precious and yours.

Claire Zalla | claire.zalla@yale.edu