I begin in September 1999. Within minutes, the expedition has become a tour with one stop too many: a law professor denouncing “measurism,” EgyptAir permitting an FBI investigation, robots joining the Yale soccer team. It is there, near the end of November, that I take a break. My right hand stings from the strain of turning hundreds of pages. The harsh white-hot lights mounted on either side of the door beat down on my hunchbacked form. Involuntarily, I breathe in more oxidized cellulose and lignin, the musty fumes of history seeping through my lung’s canals. I’m inhaling, as my co-editor put it, the smell of “Ronald Reagan’s corpse.”

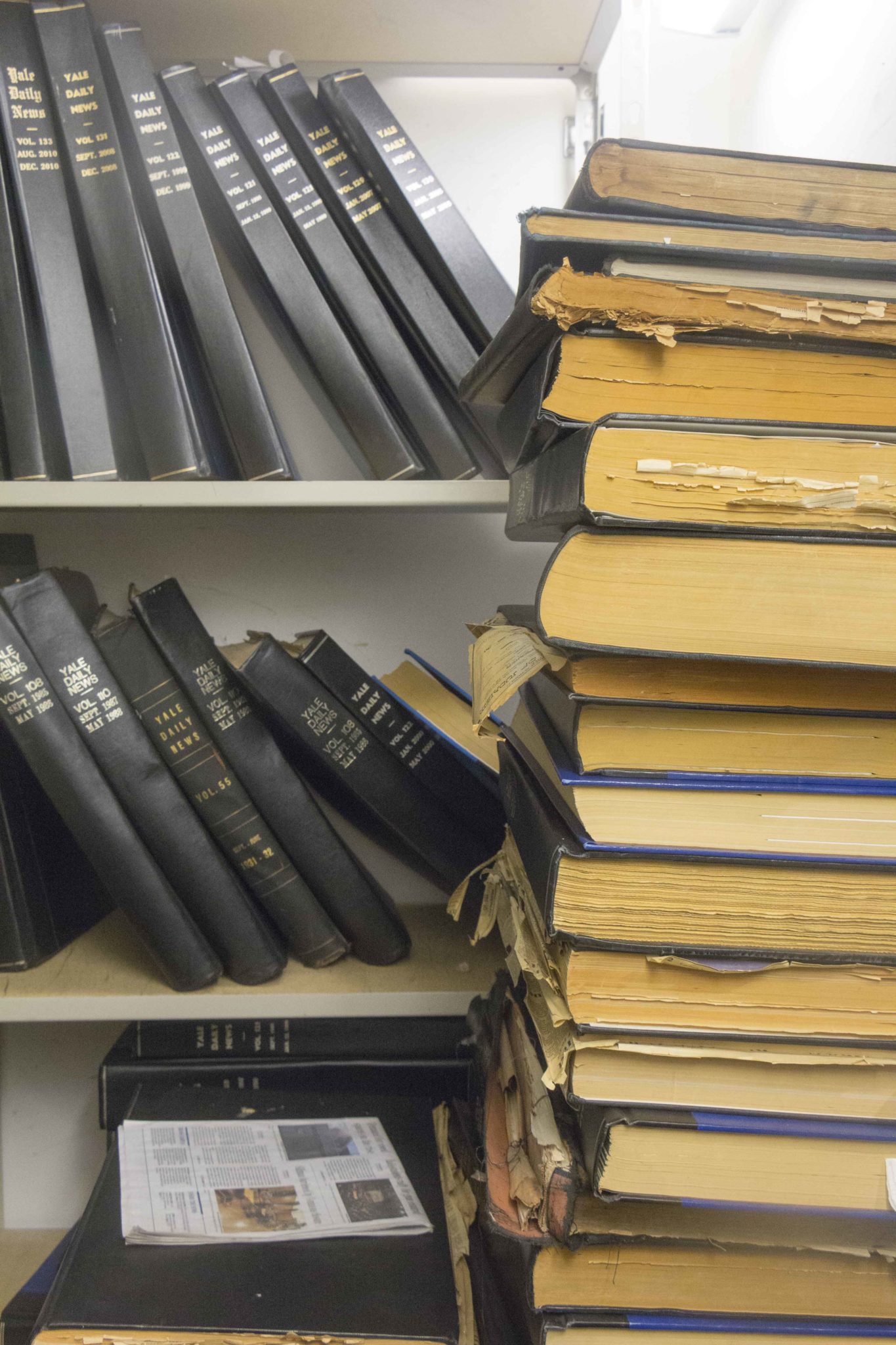

The Briton Hadden Memorial building at 202 York Street, where the Yale Daily News is written and edited, climaxes in this closet. The closet (two closets, really, together small enough for four people to stand) sits inside the building’s highest office, on the fourth floor, on the left side of the Weekend lounge, where the newspaper’s weekly culture and arts spread is produced. Ever since its founding in 1878, all editions of the News have been collected into vast leather-bound volumes divided by year, a process that former editor-in-chief David Shimer ’18 calls “maintaining history in real time.” For the past eight years, they’ve been stacked in these closets. Barely two feet from where I sit, a giant volume open on my lap, stand two columns of boxes topped by a thoughtful bottle of viscous liquid: “Old English,” a brand “trusted for over 100 years” that “restores damaged wood.” I wonder if someone left the bottle, right besides nine shelves of yellowing and browning and crumbling newspapers, as a sort of convoluted joke. It’s pretty funny.

The folks at the News call the closet “the YDN archives,” as monumental an act of flattery as any. The room defies description with a banality so determined that, according to our generation’s standard of truth, or Google, it does not exist. An online search for “ydn archive” directs me to a Yale University Library webpage boasting about its Yale Daily News Historical Archive. Hyperlinks provide instant access to digitized scans of 20,623 issues published between 1878 and 1995. The Sterling Memorial Library holds physical copies of the oldest and newest editions in its Manuscripts & Archives section. Same content, but one collection self-delights inside a neo-Gothic cathedral while the other self-deprecates in a nonexistent closet.

I imagine that if the archives ever took human form, it would be as a historian undergoing an existentialist crisis. Well, a pissed-off historian undergoing an existentialist crisis while trying to sue the YDN for malnourishment and negligence, probably. Somehow, I feel like I should pity the archives, if only because it has such a perfectly tragic backstory. In 2008, a summertime rainstorm flooded the Memorial building’s boardroom, the original site of what was then the 130-year-old archives. The result: numerous “forever-lost first drafts of Yale’s history,” as a News’ View mournfully put it after the fact. When the building was renovated in 2010, the boardroom’s shelves were emptied of the decaying YDN volumes in the interests of “visuals,” as Emad Haerizadeh, the building’s controller, so politely put it. The architects rationally spent a couple thousand dollars to buy hundreds of random and old (but not too old) books to decorate the empty space. But for all the senior discrimination, someone is more likely pick up YDN volume 45 (the roaring years of 1921-1922) than they are “English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages.” Somehow, despite overlooking every major YDN staff meeting for the past eight years, the boardroom’s multicolored books are more invisible than the funeral-black volumes concealed by closed doors.

When I ask the librarian at the front desk of Sterling’s Manuscripts & Archives section if I can see the oldest editions in the Yale Daily News Historical Archives, she tells me she will need special permission because of their “sensitive” state. Five minutes later, I am back in the YDN archives, welcomed unpretentiously by volumes from the 1880s. The Historical Archives’ online hyperlinks might have saved me an hour — I realize, when I flip from December 5 to December 8, that the YDN did not release an issue on December 7 — but now I know that Yale students once dreamed of building small robots to play soccer with them, so it’s time well-wasted. I am in 2008 now, shambling towards November 25 with as much grace as a reporter meeting a deadline. I procrastinate at the appointment of Mary Miller as Yale College’s first female dean. The election of Barack Obama. The headline praising former Master Jonathan Holloway: “Dr. J ‘is Calhoun.’” Also, there is no school during Thanksgiving Break. I take another break.

All staff reporters visit the archives during their heeling process, that G-rated initiation ritual of personality quizzes and production and design shifts that betrays the News’ guilty aspirations to semi-frathood. Stephanie Addenbrooke Bean ’17, former editor-in-chief, encouraged heeling visits to the archives “to engage interest in Yale’s history, to show how much the YDN had changed and to develop appreciation among our staff of what the YDN used to be like (for better or worse).” In theory, then, visiting the archives helps reporters gets a better sense of the YDN’s history. In practice, it helps them get a better sense of their own.

The YDN archives are a Rorschach test, blotting and pressing with millions of gallons of op-eds and articles so that the little that visitors winnow reflects their interests, intimacies and idiosyncrasies. Maya Sweedler ’18, a former managing editor and huge sports fan, wanted to see how Yale responded to the infamous 1968 “Harvard beats Yale 29–29” debacle. Managing Editor David Yaffe-Bellany ’19 searched for the articles his mother had written as a reporter in the 1980s. Former Illustration Editor Catherine Peng ’19 looked up reactions to Yale admitting its first female student, articles which reminded her that she was a “part of a project of generations that also belongs to American women.” Their personal history informs what they choose to know about the YDN’s history, and like ink drying on parchment, it is difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins. “We just don’t write the way we used to!” Maya gushes.

Former University editor Finnegan Schick ’18, too, speaks in plurals: how “we” felt anxious about the potential collapse of the Western tradition during World War II, “our” peak in the 1950s when “we” produced opinion-laden news articles, and, as if laughing with embarrassment over the antics of a midlife father, “our” weird phase of visual experimentation in the 1970s where “we looked like the Herald for a couple of years.” I consider telling him that the Herald almost put the News out of business back in the 1980s, but I’m sure he already knows. He was practically there.

Jack Barry ’18, a former WKND editor and my predecessor, agrees that the YDN’s past is a lovely place, if not a particularly romantic one. As he so elegantly puts it, “we’ve taken inspiration from the more whimsical early days when reporters used the YDN to shit on their peers’ knickerbockers.” Guilty as charged: the front-page News coverage of the Yale–Harvard Game on November 22, 1889, as archived in Volume 13, would pass as bold satire in the op-ed columns today. What else to say about reporters scolding the “Yale men” of the new football team for their “extreme folly” and demanding they improve “at once?”

My own heeling visit to the YDN archives was undramatic. I found a 1999 op-ed denouncing Professor Shelly Kagan’s crusade against grade inflation, an extended version of the grade-complaining student evaluations that Kagan still reads to his new class at the start of every semester. And of course I would find that op-ed, because I’m impressed by Kagan’s eccentricity but terrified by his harshness; because my unwillingness to take a course known for its harsh grading reveals an aversion to risk that I detest. Such random details are the key to understanding the results of my own Rorschach test. Here’s another answer key: my suspicions of empiricism (or “measurism”) as a guiding life philosophy; my excitement at riding EgyptAir every time I visited my home country; my father’s love of soccer, and my failure to match his skill at it.

I can’t find the 2011 volume, so there’s no chance of looking up my baby sister’s birthday. As I now know, the rest of my family were also born in the rare days and months that eluded fossilization in the amber pages of the YDN, in the summer or on weekends or during vacations, gemstones of time as lost to the archives as the archives are to Google. Still, my eyes can’t help but repeatedly gravitate towards the golden “1967” inscribed on the spine of Volume 88, the year of my father’s birth. Former WKND editor Noah Kim ’18 described the appeal of the YDN archives best: “I’ve always wanted to see my parents interacting before I was born. It’s that kind of weird impulse.”

When a close friend from home recently visited Yale, it was these dusty closets that awed him most. I showed him all the brochure-certified landmarks — the Branford courtyard, the Sterling nave, the Pauli Murray tower — and he enjoyed them, the way I might enjoy a museum exhibit on Modernist art: interested, but not invested. It was the actual museum, crammed in an obscure closet in a small building closed to the public, that moved him. I showed him the News’ coverage of the ongoing battles of World War I — and of course I did, because I have never stopped obsessing over the confounding causes of the War to End All Wars — and together we pored over reports about the advancement of Russian troops. He stood there in the closet, soaking in the immensity of the News as an institution more ancient than anyone alive, and told me he was proud of me.

It was somewhere in 2008, around the time that WKND still called itself “Scene,” that I paused at the staff sheet. I cannot tell you what names it listed, because I have already forgotten them. Someone, someday, probably during a heeling shift, will also find my name listed under the WKND section or whatever silly new name it christens itself, listed for all the issues produced by the Yale Daily News Managing Board of 2019. They will read the name and promptly forget it, and I will be happy—because you can’t be forgotten without first being acknowledged. I don’t need to have read all 140-something volumes of the archives to know that the recurrence of an “Ahmed” is unlikely; the appearance of an “Elbenni,” a family name from a forgotten village buried deep in the Nile delta, unfathomable. But now neither elude fossilization, and so even as the YDN archives reflects my distinct personality, it assimilates me, its latest catch, into its 140-year-old record.

That’s the paradox of the archives, perhaps, and of the YDN itself: it sharpens your sense of self even as, like a drop of ink in a puddle of water, it dilutes it. The color of the ink and the shape of the water are one. You are the News, the News is you. I can only imagine what my friend thought as I hurried him up the stairs of 202 York St., explaining that this is where “we” worked, that the dusty archives in the WKND lounge was a record of “our” history.

It is a narcissistic sentiment, almost as narcissistic as the archives itself, which is the News’ equivalent of a daily selfie. But perhaps it’s that blatant self-affection, that understated but confident sense of the Oldest College Daily’s self-importance, that makes the archives so charismatic — or, at the very least, more charismatic than two dusty closets of crumbling books have any right to be. That’s what keeps me returning to the archives, sifting through YDN volumes for hours, visiting our settled past and contemplating our fluid future, a time machine in real time. I only think to leave when, once again, the smell of Ronald Reagan hurts my lungs.

Ahmed Elbenni | ahmed.elbenni@yale.edu