“Shame on you,” chanted high school students from Florida to lawmakers who refused to make gun control policy reform after yet another school shooting.

This Valentine’s Day, Parkland, Florida, entered the ever-growing list of cities with mass school shootings. The high death toll — 17 people dead and 14 nonfatal injuries — makes it one of America’s deadliest school shootings. Now, with the inspiring surge of student activism, Parkland’s tragedy and the conversations surrounding gun laws have taken over national media coverage, renewing faith in realizing common sense gun control.

As recent as this Wednesday, the Florida legislature passed their first act in response to Parkland, which included raising the minimum age for all gun purchases to 21. But in the same breath, the bill also allowed for a provision that permits superintendents and sheriffs to arm school employees like counselors and coaches. The act, while nudging the gun control movement forward, simultaneously set back the campaign with the latter clause.

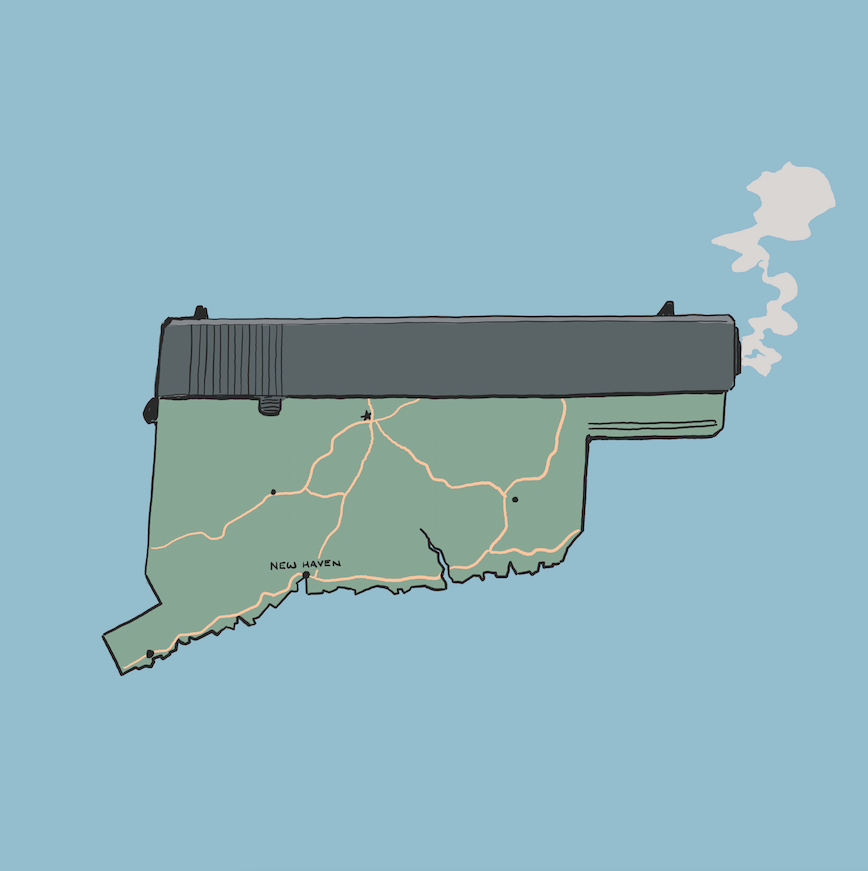

Connecticut, more than a thousand miles away, is no stranger to the epidemic of gun violence. In Newtown, the specter of Sandy Hook still lingers, a shooting that is still considered the deadliest mass noncollege school shooting in the country’s history. Though no major national laws were introduced in response, Connecticut spearheaded gun control reforms.

Connecticut has the fifth lowest firearm death rate in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a fact often touted by gun safety activists. With its strict gun control policies — the expansion of an existing ban on assault weapon sales, required background checks for all firearm sales, required registration of all existing assault rifles and higher-capacity magazines, the creation of a registry of weapon offenders and the prohibition of selling magazines with more than 10 rounds — many states now look to the Nutmeg state as a model for gun law reforms.

Though the current discourse was spurred by the tragedy in Parkland, discussions on gun violence is not simply about eliminating school shootings. Policymakers cannot ignore nonschool-related gun crimes like street shootings and gang violence. Michael Sierra-Arevalo GRD ’18, a sociology student who focuses on practices of police officers and has published research on street gangs, firearms and violence reduction, explained that reducing gun violence from mass shootings may not affect reduction of urban gun violence. Although he acknowledged the success of Connecticut’s stringent gun reforms, he said a ban on assault rifles — which may or may not actually affect the occurrences of school shootings — is “unlikely to move the needle on gang violence, which usually takes place with small-caliber, cheap, easily available firearms that have nothing to do with the AR-15.”

Connecticut’s gun reforms are admirable; after all, a 40 percent reduction in the state’s firearm-related homicide rate is associated with the state’s 1995 handgun purchasing law, according to a research published by the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; however, legislators still have work left to reduce gun violence in its own state.

Still, young adults and students within Connecticut have already put forth initiatives and proposals to mitigate gun violence. This past winter, Rohan Naik ’18, collaborated with New Haven to run a gun buyback program, in which the police department collected guns from local citizens and offered gift cards in return. Prison inmate volunteers melted the surrendered weapons into gardening tools for students to harvest vegetables for soup kitchens — a modern swords-into-plowshares event.

Naik explained that he had read about a buyback project in Los Angeles, which inspired him to do a similar project in New Haven. He contacted the national nonprofit Gun by Gun, the New Haven Police Department and the Yale New Haven Hospital to organize a gun buyback on Dec. 16, 2017. The buyback yielded 141 weapons.

While the buyback was successful, Naik recognizes that this type of initiative is only a Band-aid on a larger problem.

“What we need to stop gun violence is actual gun reform,” says Naik. “The gun buyback is the bare minimum.”

Additionally, gun buybacks are not simple. After all, this type of project requires extensive capital and needs to target “people who are gun collectors to ensure that we’re getting guns that would be potentially used in crimes,” Naik notes.

However, the gun buyback draws on community support and increases publicity for the gun control debate within New Haven and Connecticut; the buyback allows citizens to directly counteract gun violence. Naik explains that he wants to do another New Haven buyback in June, but also hopes to increase student involvement in campaigns for comprehensive gun law reform.

Another Yale student, Ananya Kumar-Banerjee ’21, explained that following the Parkland shooting, a fellow student had expressed that they were really upset, but didn’t know what to do about it.

Kumar-Banerjee, along with Carrie Mannino ’20, a Weekend editor for the News, were inspired to organize a vigil here in New Haven.

“There’s a lot of pain in the community, and it felt important that people who were grieving and knew people [who had been affected by gun violence] or were personally affected knew that there was a community that could be there for them,” Kumar-Banerjee explained.

The Yale vigil was another demonstration of student efforts to unite the local community toward the common goal of pushing for gun reforms. Kumar-Banerjee highlighted that Connecticut has already implemented strict gun laws that have vastly dropped the amount of gun-related crimes and injuries within the states. Now the next step is to push for similar gun control initiatives around the nation.

Jordan Cozby ’20, president of the Yale College Democrats, noted that students around the country may not only feel worried and upset, “but for a lot of people in our generation — anger.”

“We have seen so many instances like [the Parkland shooting] that it has caused a deep sense of frustration amongst a lot of people who have been asking about this issue,” he added.

Students in Connecticut and New Haven are already providing community engagement opportunities to push for changes in gun laws, but even Connecticut’s active gun control reforms may be unable to easily influence the gun violence rates in other states.

For Cozby, the tragedies seem to bring potential for a movement, but “very rarely does this translate to concrete action.”

“I hope that these reactions this time will be strong enough that the people in government–including the Republican Party — will choose to pursue measures to reduce this epidemic of gun violence or put into positions of power — people who will do the right thing,” says Cozby.

Senator Chris Murphy, D-Conn., emphasized the effectiveness of Connecticut’s urgent response to its school shooting. “Parkland is going to discover that there is no recovery from something like this. Sandy Hook will never ever be the same place that is was before all those little children were erased from the earth in a hail of bullets lasting under 5 minutes,” Murphy wrote in an email to the News. “It is only public policy that can solve this.”

Since enacting stricter gun laws, Connecticut has seen significant reduction in gun homicides. Murphy warns that states that “do the bidding of the NRA have higher gun [violence] rates.” States that pass “smart, common sense legislation” may finally witness a difference in their gun-related crime rates. However, state legislators in Connecticut can do little to influence the reforms of other states.

Waiting for other states to follow Connecticut’s lead may never happen; states have had drastically different responses to school shootings. While Connecticut increased background checks and prohibition of certain assault rifles, states such as Texas have instead advocated for arming teachers, increasing the presence of guns within schools.

Sierra-Arrevalos, a Texas native, underscored the historical and cultural differences between states that form difficult obstacles for gun-control agreements. He notes that states like Texas hold values of individual liberty and self-defense dearly. This means solutions to gun violence do not translate into access restrictions, but instead focus on increasing individual liberties.

“In this case,” Sierra-Arrevalos said, “it means providing more firearms to be available to people to protect themselves — from rapists, gang members and school shooters.”

However, Sierra-Arrevalos mentioned that evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that more guns lead to increased likelihood of death and injury, instead of reduction. Sierra-Arrevalos explained that arming teachers, who are largely untrained, and expecting them to “overcome the massive wave of endorphins and adrenaline that affects officers and soldiers” and neutralize a threat with an AR-15 is “absolutely ludicrous.”

Gun laws in other states need to change for noticeable nationwide reduction in gun violence. Guns can easily cross state boundaries, and as Naik explained, “one can acquire a gun in a nearby state with less strict guns laws, find [their] way to Connecticut and cause a lot of damage here as well.”

As we saw in December of last year, the U.S. House of Representatives approved the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act that would ease restrictions on interstate concealed firearm carry, pushed by the National Rifle Association only a few weeks after the Las Vegas and Sutherland Springs mass shootings. The act has been referred to the judiciary committee, and, if passed, could allow individuals with concealed carry permits from states with less restrictive laws to carry their weapons into states with more stringent restrictions.

Chicago is an instructive example; though it has one of the most stringent gun laws in the U.S., different neighborhoods have varying gun laws. As Sierra-Arrevalos explained, guns can move easily and can last for decades.

“Having very strict controls on firearms in one place that is surrounded by places that don’t have strict controls means access to firearms [is] just a short drive away,” Sierra-Arrevalos added.

While the surge of student activism here in New Haven and across the country is pushing gun control onto the fore of the national agenda, true change cannot happen without the cooperation of other states or federal action. One state’s effort must have firm cooperation from other states to enact meaningful change for gun violence nationwide.

Allison Chen | allison.chen@yale.edu