“We hold as fundamental that: Women and men are equally capable of doing excellent science.”

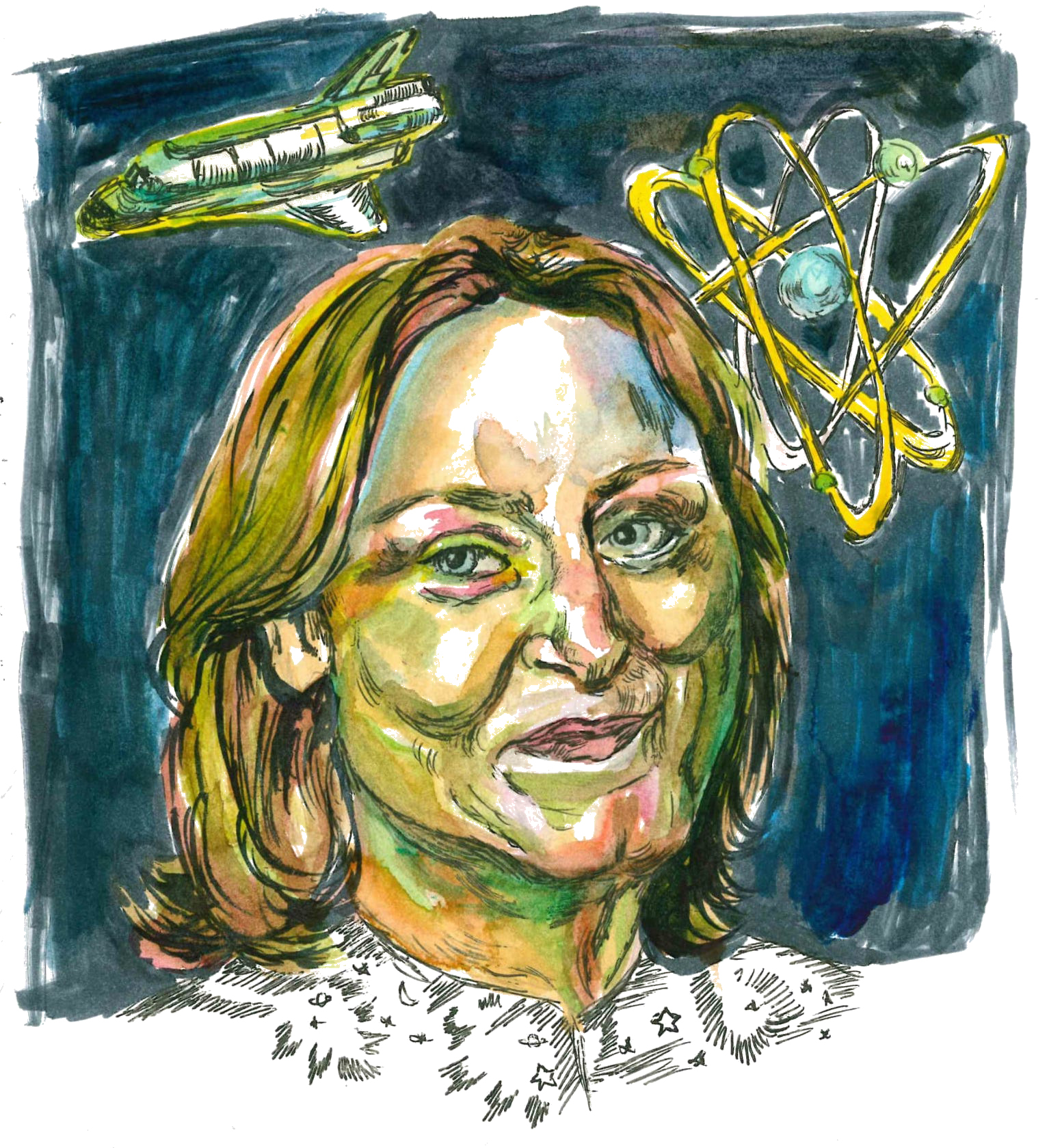

These are the first lines of the Baltimore Charter for Women In Astronomy, a product of the first Women In Astronomy meeting in 1992. Physics and astronomy professor Meg Urry, who organized the conference, said she was moved by the sight of 150 women in astronomy — a field that in the 1990s was even more male-dominated than today — in one room.

“Oh my gosh, there’s a lot of us,” Urry recalls thinking. “Let’s stop being so isolated and let’s put our voices together and make change.”

This drive for change is central to Urry’s long history of outspoken advocacy for women in science and to her role as a mentor at the University.

Urry, who comes from a well-educated family, said, growing up, she enjoyed privileges that others did not have.

“I have a responsibility, and any student here has a responsibility, to make the world better for those who are less privileged. You can’t fix everything. But I try to make things better,” she said.

Her desire to change the status quo began when she was a postdoctoral fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the late 1980s. Early in her career, Urry was told by men that she would have advantages — that being female would give her preferential treatment. Not only was it wounding, but inaccurate as well, she said; there were no advantages to being female in the field.

Talented women were often overlooked, passed over for promotions or hiring positions, Urry said. Searching for answers to this issue, Urry turned to social-science literature. The research showed that most people think women are inferior and have poor leadership skills, she said.

Urry underscored that the composition of the field was both unfair and unproductive. White men make up only a portion of the population, and taking talent from that single group is just “dumb,” she said, since members of a group of similar people are unlikely to learn from each other.

“These days it’s fashionable to say that liberals should be talking to conservatives, because they’re off talking to each other on their Facebook pages and everybody’s in their bubble,” Urry said. “Science has been in a bubble for a long time. We need to broaden it and bring in people who disagree with us.”

After her time at MIT, Urry began working at the Space Telescope Science Institute in 1987. She developed a name for herself in the field after others read her writing on issues facing women in science, ranging from sexual harassment to discrimination.

Yale astronomy professor Debra Fischer first heard of Urry at that time and said she was a “beacon in the community, especially for women who needed someone like that.”

Urry began teaching at Yale in 2001. For Fischer, Urry’s presence in the Physics Department was an important factor in deciding to come to Yale.

Urry recounted an experience early in her career when a physics major wanted to see her because she was the only woman faculty member in the department. They got to talking about graduate school, and the student said she thought she was not smart enough for physics. Asked about her grades, she revealed that she was getting A minuses and B pluses in class.

When she heard that, Urry was surprised. The student was at one of the toughest universities, doing an exacting major and getting good grades. Still, she thought she was not good enough.

“It’s not that I know the truth, but I do know crazy thinking when I hear it,” Urry said.

Fischer described Urry as a proactive colleague but also a good personal friend. When Fischer’s adviser, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, was found guilty of sexual harassment two years ago, she found it very helpful just to talk to Urry and use her as a sounding board.

Over the course of her career, Urry has strived both to mentor women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics and to make a broader impact on students’ lives. When a student is struggling, the solution may be as simple as working in a group or watching the lecture online. But understanding a particular student’s situation and finding a solution can be trickier.

“That’s what you need to do to mentor well, and it’s an impossible task,” she said. “But I do know if you stay where you are, just being you, you’re going to fail most of your students. They’re not you and they don’t act like you act.”

Urry also has a group of postdoctoral fellows, graduate students and undergraduate students that meets weekly and shares progress in projects.

Dominic Eggerman ’18, who took Urry’s “Physics 181” class during his first-year spring semester and is part of her group, said that Urry is a mentor figure and the first person he goes to with questions. And Meredith Powell GRD ’19, a graduate student who has been working with Urry for two-and-half years, said that after their first meeting, she got the impression that Urry not only was intelligent, but also cared about her students and was a great mentor.

Urry is incredibly busy, Powell added, but if you need something, she will always come through. During her interview with the News, she paused to take a call about a graduate student’s recommendation letter.

Urry said she does not expect her research to change lives. Still, she added, some of the greatest scientific advances in recent history have come from unexpected places.

“I don’t see an immediate application for that knowledge. But this is, in effect, knowledge for knowledge’s sake,” she said. “And … history shows us that knowledge often has an impact that is totally unpredicted and totally changed the way the world works.”

Eui Young Kim | euiyoung.kim@yale.edu