After settling the Calhoun College naming dispute, Yale administrators are looking toward the future as they plan the University’s next big fundraising push.

Yale is currently in the first half of a two-year planning period before kicking off a new capital campaign, a major fundraising effort usually tied to specific institutional goals, like the construction of a new building. Yale has not held a capital campaign since former University President Richard Levin concluded his last one in June 2011 after raising $3.881 billion.

Vice President for Alumni Affairs and Development Joan O’Neill told the News that Yale is planning to hold a traditional campaign: a two-year “silent phase” during which the University raises at least a third of its overall goal before publicly announcing campaign targets, followed by an additional five years of fundraising.

“We don’t know what our goal is yet, but that stuff we’ll be working out over the next year,” O’Neill said. “A lot of schools have done longer campaigns, like 10-year campaigns, and some are saying we should do a shorter campaign, but right now we’re planning to do a pretty traditional campaign.”

But Yale’s fundraising plans could be complicated by the racially charged controversies of the last 18 months. In February, the Yale Corporation voted to rename Calhoun College, the controversial namesake of which has divided alumni for decades. According to O’Neill, the dispute over Calhoun — among other race-related campus controversies — has been “a distraction” during Yale’s fundraising efforts over the last two years.

“There will be people who will decide [the renaming decision] is the reason they wouldn’t want to give — there’s no question,” she said.

Yale’s capital campaign will also be the first chance for University President Peter Salovey to lead a major fundraising push since he took office in 2013. As dean of Yale College and later provost, Salovey was involved in the capital campaign that ended in 2011.

In an interview on Wednesday, Salovey told the News that the University has prepared for the capital campaign by examining fundraising efforts at other universities as well as the history of philanthropy at Yale.

“We are doing some planning work that will continue next year where we ask the question: What are our biggest needs? What would those needs cost us to address? And which of them would be especially attractive to donors?” Salovey said.

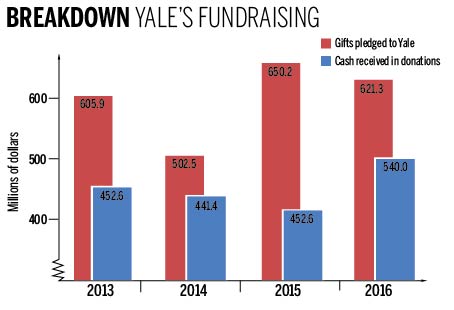

Last year, the University accumulated a total of $540 million as a part of its regular fundraising efforts, an increase of around $90 million from the year before. According to the Council for Aid to Education, Yale ranked 10th in fundraising among American universities in 2016, trailing peer institutions like Columbia University, Harvard University, Stanford University and Princeton University. The CAE rankings are calculated based on the cash amount accumulated in a given year, rather than pledges promised for future years — the standard Yale uses to measure itself internally.

“There’s no question that Yale’s fundraising needs a shot in the arm,” said former University Secretary Sam Chauncey ’57, noting that the CAE ranking is “from a pride point of view, pretty bad.”

According to Chauncey, that fundraising weakness could signify that the alumni are “restless.” After the Corporation voted to rename the college in February, more than 100 alumni from the ’50s and ’60s emailed him to complain, Chauncey said.

In an interview last month, Calhoun alumnus Joe Staley ’59 told the News that the renaming decision has angered many of his former classmates, including at least one acquaintance who is threatening to withhold a multimillion-dollar donation.

Still, O’Neill said she remains confident that Yale will eventually win back alumni who are unhappy about the Calhoun decision, comparing that process to the University’s efforts to pacify alumni whose children or grandchildren are rejected during the admissions process.

“They may not want to talk about Yale, but they may feel better with a little bit of time,” she said. “It may be that they don’t make their annual gift this year, but we hope that we get them back.”

Moreover, many Calhoun alumni either support the renaming decision or do not feel strongly about the outcome of the debate. William Casarella ’59 said he does not plan to give any less to the University because of the name change, which he described as “not a big deal.”

In the long term, Yale hopes to use the capital campaign to reorient the University away from renaming and toward its long-term institutional priorities, such as funding for the sciences, greater integration of the different art schools and enhanced public policy offerings, Salovey said.

“Alumni love Yale, but they want to give to projects and people at Yale that make them proud,” he said. “It’s incumbent on us to make those targets for giving salient, but that’s hard to do in the midst of controversy.”