“Oh mankind, indeed We have created you from a male and a female and made you peoples and tribes, so that you may know one another” (Quran 49:13).

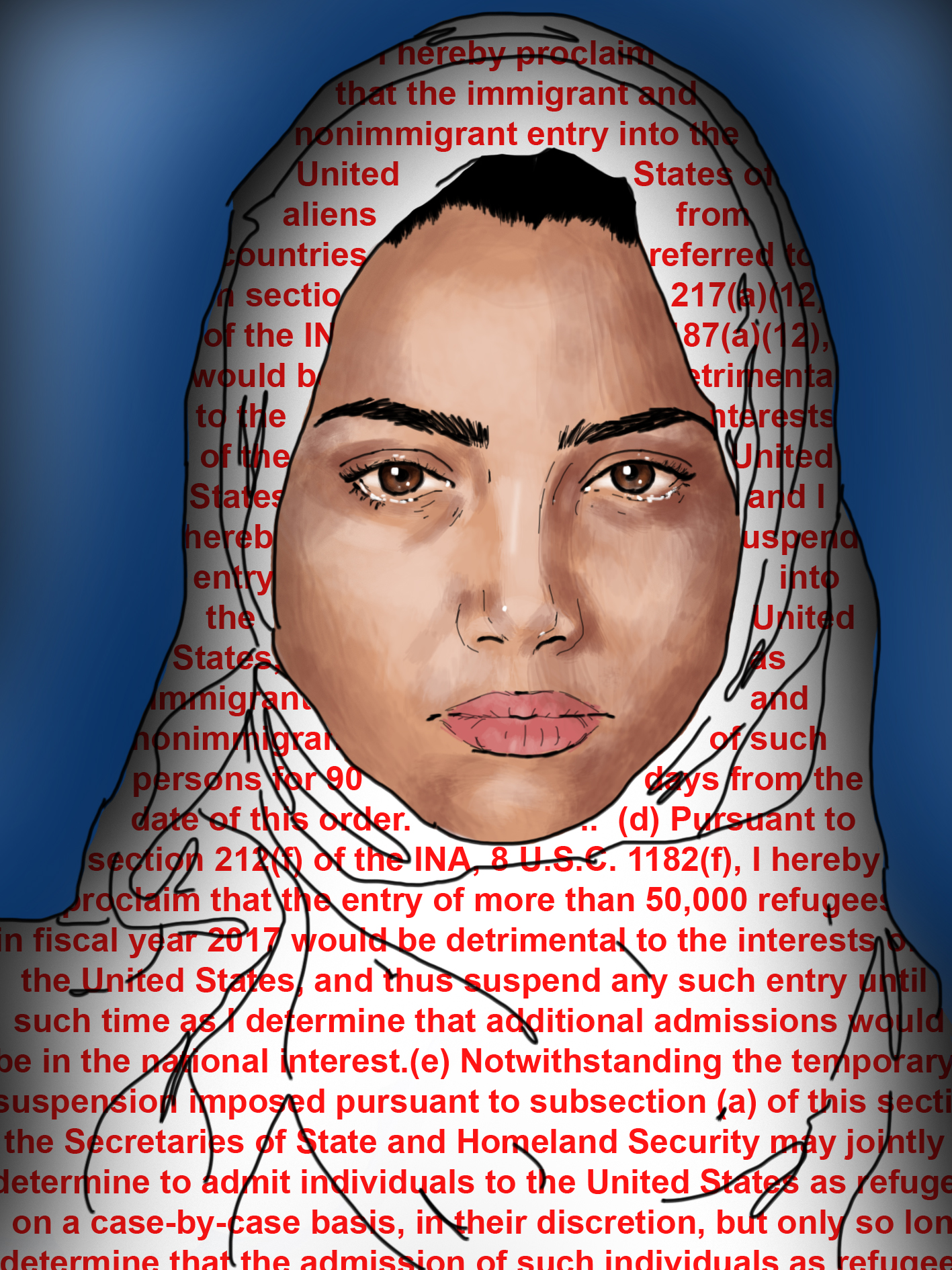

By now, we’ve all heard the refrain: banning refugees and immigrants from the United States, and those of a particular faith no less, is “un-American.” And the refrain’s absolutely true. This country prides itself on taking in the tired, poor, huddled masses “yearning to breathe free.” What there has been less talk of since President Trump’s controversial executive order, however, is an equally important reality: that Islam is a religion of immigrants, both literally and metaphysically.

None of the first Muslims were native, so to speak. None of them, after all, had been born into the religion. Each and every single one of Prophet Muhammad’s first followers made a conscious decision to leave behind the societally acceptable traditions of their forefathers to join a religious minority that suffered from systematic persecution and marginalization. They made this decision in defiance of crippling social pressure and with a grim awareness of the potentially fatal consequences.

The literal immigration followed the spiritual one. After enduring 13 years of starvation, torture and violence, the Muslims immigrated from their home city of Mecca for the safe haven of Medina, which had promised to take the battered refugees in. Leaving behind their homes, their culture and the very center of their reality up to that point could not have been easy. The Prophet, deeply attached as he was to Mecca, was especially pained to let it go. He vowed to return to it someday, and 10 years later his wish came true. And yet, ultimately, he opted to continue living in Medina until he passed away. It was, after all, the community that had greeted him and the other believers with open arms, the society that had demonstrated a remarkable capacity for compassion and acceptance. It had become his new home.

If one had been at that new home, Medina, the heart of the Muslim community in Arabia and the point from which Islam would spread across the globe, one would have seen a city as diverse as any in the U.S. One might have heard the melodic call to prayer at the mosque, delivered by Bilal, a black man and former slave. One might have seen Salman, a Persian and former Zoroastrian, advise the Prophet Muhammad on military strategy. One might have seen Aisha, a distinguished Islamic scholar and political activist, give one of her eloquent lectures.

Islam’s universality is reflected in its own name: “submission.” It does not anchor itself to an individual figure or a particular place, but instead describes a spiritual act that can be undertaken by anyone. Islam is not Arab or Asian, European or Australian, white or black, and yet it is all of them and more. The scornful medieval European scholars who once called Islam the “Mohammedan” faith, casting it as the evil counterpart of the Christian faith, missed this nuance.

But while Islam may not be strictly about the Prophet Muhammad, no one provides a better embodiment of its principles than he. Aisha, who was also the Prophet’s wife, once called him a “walking Quran.” Muslims see, in the Prophet’s example, the crystallization of the Islamic ideal of peaceful coexistence and embrace of human diversity. We recognize it in the constitution that he drafted in Medina, which declared the prominent Jewish population “one community with the [Muslim] believers,” thus establishing a truly multicultural and multireligious state. We recognize it in his gracious treatment of the Christian delegation from Najran, whom he allowed to pray in the mosque before their debates over matters of faith. And we recognize it in the words of his last sermon, where he unequivocally stated that “an Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab any superiority over an Arab, and a white has no superiority over a black nor a black over white, except by piety and good actions.”

Islam has immigrated to all corners of the world, and all corners of the world have immigrated to Islam. It rejects no one. A religion that first spread on the Arabian Peninsula today finds the majority of its followers in Southeastern Asian countries like Indonesia and Malaysia. In that sense, America’s principles of diversity, tolerance and acceptance is in full harmony with Islamic values.

We’re better than this. Let us be American. Let us be Muslim.

Ahmed Elbenni is a member of the Muslim Student Association and has written this article with its input and on its behalf.