Ishrat Mannan ’17 stood by a lonely table, pamphlets in hand. Her disinterested classmates streamed past her, lining up to attend the event of the day: a talk by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, titled “Clash of Civilizations: Islam and the West.” Even though the physical distance that separated them could not have been more than a few feet, Mannan found that she and her fellow Yalies might as well have been in different ideological worlds. In one, Islam was a symbol of peace and a way of life. In the other, it was a foreign relic of a bygone era, interesting to study but not to take seriously. “That huge divide,” recalls Mannan, “just felt really, really disheartening.”

The divide was not some “civilizational clash” between Islam and the West. It was not between Muslims and Yale; indeed, that was the false narrative that Mannan and her companions wanted to speak out against. The real divide, as is often the case, was between what Islam meant to her and what it meant to others. Most people, including Yalies, may not know much of Islam beyond what they have watched on CNN and read in The New York Times.

I’ve answered many questions about my Islamic faith since setting foot on campus: whether I pray, when I fast and what I think of terrorism. They are questions my eight-year-old self would have been able to answer just as well. The reality I see, that Muslim students are part of the Yale family, leading fascinating lives, may not feel as real to my classmates.

There exists no prototypical Muslim student; they all come from backgrounds as diverse as the Yale community, bringing with them unique cultural and personal perspectives on how to practice their faith and live their lives. There are those who spent their entire lives in a non-Muslim environment, and so were pleasantly surprised to find a ready-made, closely knit community here. Others knew nothing but Islam their entire lives, and felt challenged by the new world Yale represented.

Muslim students carry their faith with them wherever they go, a guiding presence that helps keep their spiritual and material lives balanced. Many of them have a fundamentally different view of a day’s structure than most students do, courtesy of the Islamic mandate of five prayers a day. There is the large chunk of time between the morning (Fajr) prayers and the noon (Thuhr) prayers, the briefer period between the noon and afternoon (‘Asr) prayers, the even shorter span of time between the latter and the evening (Maghrib) prayers, and the final segment between the evening and night (‘Isha) prayers. Since Yale does not recognize these prayers, it is up to the responsible Muslim student to find a way to craft a class schedule that still permits some time, however brief, to fulfill these essential religious commitments. Muslims can pray anywhere, mosque or no mosque, as long as the setting is clean. Of course, that does not always mean the setting is ideal.

“The other day, I was praying in a stairwell,” Zaki Bahrami ’18 recalls. “I was praying with two of my friends. It was funny, because someone opened the door and slammed my knee, while I was kneeling and praying.”

Finding the space and time for prayers is just one example of the challenges that Muslim students at Yale may face on a daily basis. They also abide by dietary restrictions, eating only halal food, which sometimes affects the dining hall experience; the pang of disappointment that greets me whenever the chef shakes his head about the delicious-looking chicken on the counter doesn’t get old. Drinking is also prohibited, as is premarital sex. Still, these tests are not necessarily unique to Yale. “I don’t think that Yale itself has an effect on an individual’s practice,” says Ahmad Aljobeh ’16, former Muslim Students Association president and aspiring medical student. “Wherever you are there are going to be some kind of challenges, and Yale isn’t special in that regard.”

If anything, Aljobeh believes the abundant resources available to Muslim students, such as the Chaplain’s Office, make Yale more supportive of Islamic practice than many other colleges. Yale’s Coordinator of Muslim Life Omer Bajwa affirmed, “You can be a practicing, committed Muslim and also be an excellent Yale student and have a wonderful Yale experience.” The question seems not whether Muslims can be Muslims at Yale; it is whether other students can accept, and appreciate, that fact.

Courtesy of Yale MSA

Acceptance can be hard in a place as secular as Yale. Students discuss God largely in the abstract, perhaps as a literary symbol or as an interesting thought experiment. In a philosophy section, my classmates spoke of religious people in the third person, as people that are perhaps a little less “rational” than everyone else. I sensed, as I often did at Yale, that my classmates shared an unspoken but tangible understanding of religion as a mold that everyone outgrew a long time ago. I sat there awkwardly then, wondering if that made me a child who had accidentally wandered into a room of adults.

The abandonment of serious religious belief is doubly difficult for Muslims, who also have to deal with the constant scrutiny of a restless media cycle hell-bent on making “Islam” synonymous with “terrorism.” Considering the image of Islam seared into the American public consciousness, it probably is not surprising that the religion is most commonly spoken of at Yale in that context. Whether it is in Global Affairs or Modern Middle East Studies, Islam is usually taught from the specific viewpoint of radical violence and national security. It’s not that good classes about Islam don’t exist at Yale. Rather, it’s that students choose not to take them.

“[Classes about Islamic civilization] are not the popular, sexy classes that get high attendance,” says Bajwa. “Muslim civilization, Muslim history, intellectual history, social history, Muslim culture’s contributions to society, those are the classes that have anemic attendance.” There is no doubt that the content of the media’s Islamic coverage has popularized classes about war and fundamentalism. The dangerous consequences are equally obvious: After constantly learning about Islamic extremism, people may come to understand the religion through that lens only, ignoring over 1400 years of history and culture in the process. Professors often frame Islamic issues in provocative fashions that “sell,” according to Bajwa.

Yale’s general academic attitude toward Islam is just the tip of the iceberg. If anything, it is reflective of subtle Islamophobia on parts of campus. This tension between the Muslim and non-Muslim Yale communities has manifested itself more than once in Yale’s recent history.

Seven years ago, the master of Branford College invited Kurt Westergaard, one of the 12 Danish cartoonists who drew offensive cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in 2005, to a Master’s Tea. Westergaard’s cartoon depicted the Prophet wearing a turban shaped like a bomb. The event caused more than a little controversy, drawing in the Yale administration and sparking the Muslim community into action. “When we attended the event, we had all of these polished questions,” says Umar Qadri ’11, a junior at the time and a current medical student at Duke. “We tried to [challenge him] from an academic perspective.” The questions were meant to force Westergaard to defend his actions before his audience, and Bajwa thinks they succeeded in that regard. As such, despite the initial negativity surrounding Westergaard’s appearance, Bajwa ultimately views the incident positively, as it was an effective showcase of the intellectual prowess of the Muslim student body and its willingness to engage with divergent ideas, even if it finds them offensive.

Then in 2012, the New York Police Department’s massive spying operation on at least 15 Muslim student organizations across the country came to light, and with it the revelation that Yale students had been the unwitting targets of extensive surveillance, suspected solely on the basis of their religion. The incident hit hard, but fortunately the Yale administration issued a statement of support for the Muslim community on campus, with former University Vice President Linda Lorimer telling the News that Yale “supports [the MSA’s] goals and aims and is grateful for its leadership on our campus,” adding that she had been “both inspired and educated by the MSA.”

Perhaps the toughest blow, though came last year, with the William F. Buckley Jr. Program’s invitation of Hirsi Ali, a well-known anti-Islamic speaker. Several students were offended that someone without Islamic scholarly credentials was coming to testify specifically against the religion, and they protested the invitation. A few proposed inviting a second speaker with contrasting views to Hirsi Ali, so that the audience could receive a more balanced overview of the issues at hand. The Buckley Program saw the MSA’s actions as attempts to control its activities and curtail its rights, and it resisted.

What started off as a small event exploded into a raging firestorm that drew in the national media and numerous student organizations across campus. Arguments were made, op-eds were written, letters were sent, and before anyone knew it, Hirsi Ali’s event had somehow evolved into an epic showdown between protecting free speech and preserving a safe space. In some ways it was an eerie foreshadowing of the student upheaval that took place last semester, which resulted in the formation of Next Yale. “A lot of people have become very open about how disillusioned they are with Yale,” says Mannan, who handed out dissident pamphlets at the Hirsi Ali event. “It feels like echoes of what I was feeling as a sophomore.”

Unlike last semester, though, the controversy never snowballed into something greater. In contrast to the show of support shown in the aftermath of the NYPD spying controversy, the Yale administration never got involved. The event proceeded without a hitch, with over 300 students attending. The MSA did not interfere, settling instead for handing out pamphlets critical of the event outside of its entrance. Still, the overwhelming consensus amongst the Muslim community was that it was a loss to them and yet another hit to their already nationally fractured image. Muslim students still recall the incident vividly, and it seems that raw and bitter feelings still linger.

“It was such a dated [concept],” says Didem Kaya ’16, a senior from Turkey majoring in American Studies, referring to the talk’s central theme of a civilizational clash between Islam and the West. “It was kind of a sad moment to see that my Yale classmates were so far behind.” Despite the support shown by multiple organizations toward the MSA, much of the wider Yale community appeared to disregard the opinions of Muslims about an issue that concerned their own religion. “I think our voices were not important,” says Bahrami. “Each individual Muslim, I think, has [non-Muslim] friends that really care about what that Muslim has to say … but outside of those very close immediate friends, most people don’t care what Muslims think.”

But even as Muslim students continue to push to have their voices heard, there are signs that the Yale community is becoming more receptive to their complaints. The MSA, backed by administrative support, has become much more active, especially since the appointment of Bajwa to the position of Muslim chaplain in 2008. Before Bajwa, the MSA was entirely student-run and had a membership of 30 students, roughly the size of the MSA’s freshman class today. In the absence of a strong support system, board members had to find creative ways to accommodate the needs of the Muslim student community. During Ramadan, the holy month of fasting in which food and drink is prohibited from sunrise to sunset, the board would arrange suhoor packets of food that students would consume in the early morning in preparation of the hungry day ahead. They would also put together an iftar meal at the end of the day for breaking the fast, and sometimes schedule impromptu prayers late in the night. Students would take on the responsibility of delivering the weekly Friday sermons and prayers, a task of immense importance in Islam.

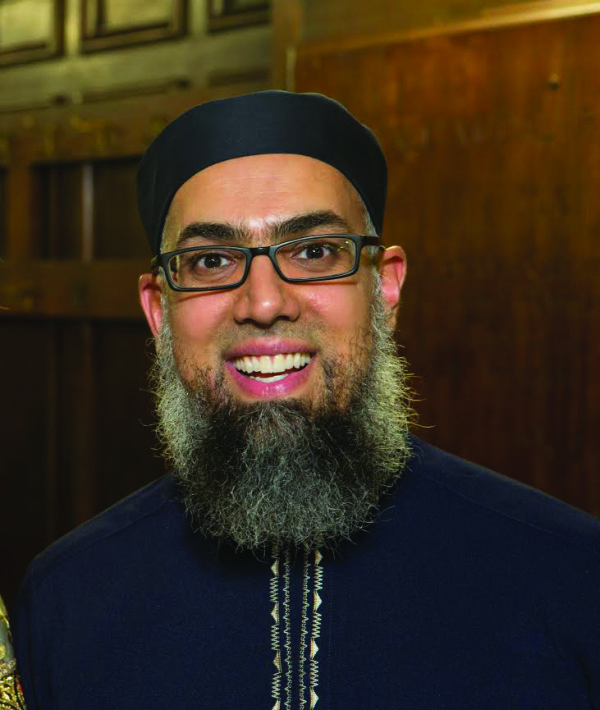

“[Bajwa made] the MSA a more ‘legitimate’ organization,” says Qadri. “The needs of the Muslim community became more known to the larger administration with him as our chaplain.” Attendance at Friday prayers has more than tripled during Bajwa’s tenure. He has become the face of the Yale Muslim community, issuing important responses on its behalf while also reaching out to other faith-based organizations. Whether being interviewed by graduate students studying Islam or offering advice to troubled individuals, Bajwa functions as both a Muslim authority and a personal mentor; in his own words, “a pastoral caretaker.”

Photo courtesy of Omer Bajwa

The MSA now holds several major Muslim events throughout the year, from the lavish Eid Banquet in Commons (which Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway attended this past October) to the Yale-hosted spring Ivy Muslim Conference, which brings together hundreds of Muslim students from across the Ivy League for two days of spiritual reflection and social activities. A halaqa, an hourlong Islamic gathering headed by the chaplain, is held every Monday, and students enjoy a halal dinner at the Timothy Dwight dining hall every Wednesday. The MSA also runs ordinary social events like trips to a bowling alley and stargazing. And, most importantly of all, the MSA strives to be a safe space where members can be brothers and sisters, helping each other remain spiritually grounded in their shared faith.

In addition to hiring a Muslim chaplain, students say Yale’s senior administration is making an effort to increase collaboration with the Muslim community. Holloway recently held a meeting with members of the MSA, hearing their concerns and proposed solutions to long-standing issues. Yale is looking to hire a new religious studies professor for Quranic Studies, an initiative which represents an opportunity to diversify Muslim faculty representation and improve the academic diversity of the institution’s Islamic education.

With these steps, it is not impossible for Muslim students to imagine that Yale could someday truly rise above the Islamophobic paranoia that characterizes so much of modern American politics. And many hope for a future where the Muslim community can continue to grow and thrive.

“I’m just waiting for our own building. Our own Slifka Center, our own dining hall,” says Aljobeh with a laugh. “I dream big.”