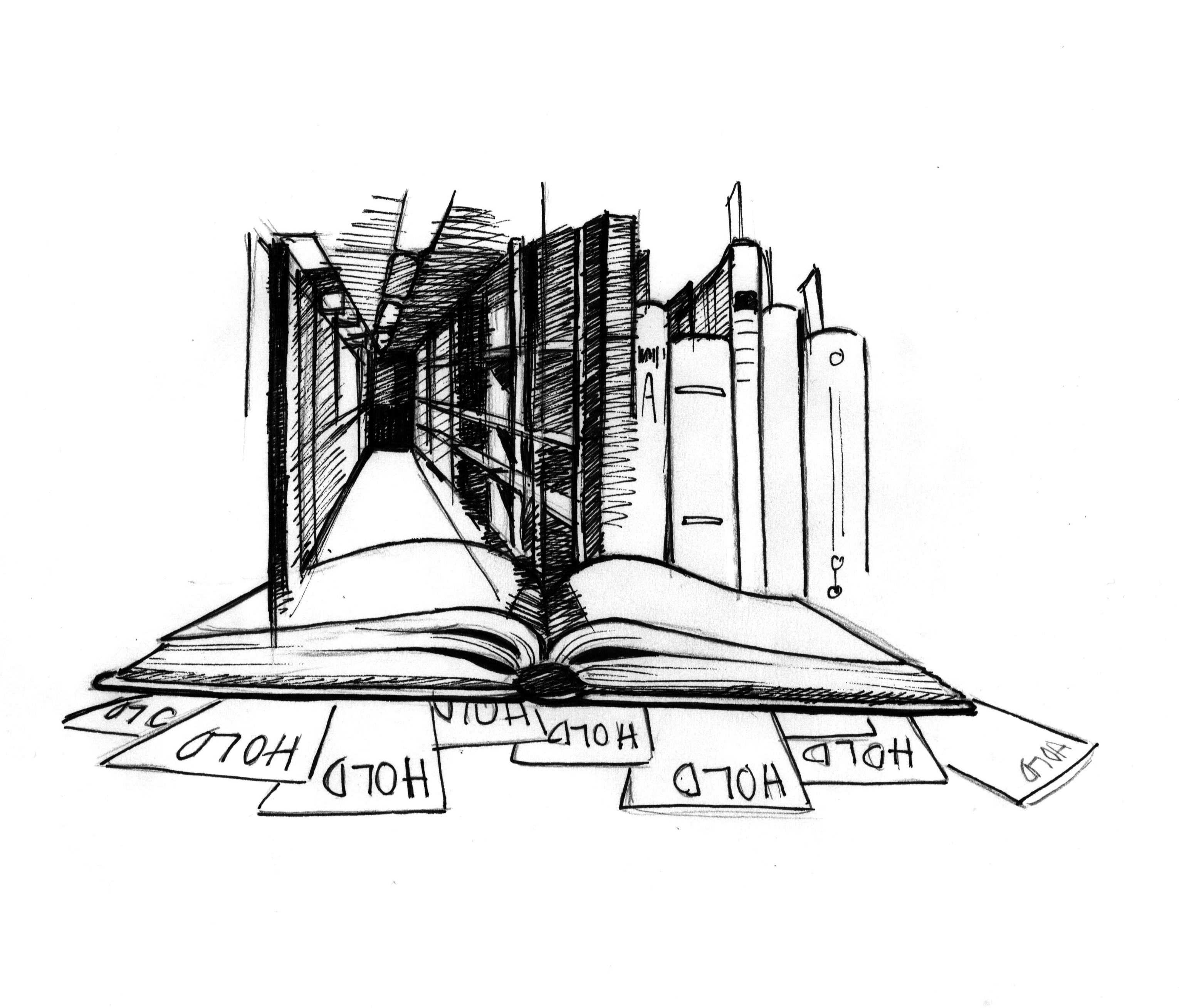

I have a confession to make: I am a voyeur — an intellectual voyeur. In my free time, I sometimes go to the hold shelves in Sterling Memorial Library, located in the room between the majestic nave and the soulless stacks. There, I examine the unsuspecting books, waiting to be checked out by some student or scholar, redeemed after years — perhaps even decades — in purgatory.

That room is my favorite place at Yale. It is completely stripped down, functional and unpretentious. The collegiate Gothic architecture of Harkness Tower may be stunning, and the vastness of Commons might inspire awe, even terror, but the hold shelves embody what the university is truly about.

On the hold shelves, a biography of Van Gogh can sit right next to a monograph on the origins of the Equal Rights Amendment; a compilation of nineteenth century literary magazines can lie next to a Russian tract on Soviet-era economics. Despite a great deal of ideological convergence on a number of sociopolitical issues at Yale, the hold shelves alert us to the intellectual diversity which continues to animate much of the academic enterprise.

In an age of overspecialization, the hold shelves serve as a reminder of the books I will never read or even know existed. As we grow more attached to our fields, it is easy to fall into the trap of believing that what we do or study holds the key to the world. The hold shelves humble us, for they expose the many doppelgängers out there, working equally hard on projects with just as much merit and significance as our own.

As I look at the hold receipts sticking out of the books, I sometimes wonder about the patrons who made those requests. These are people I have never met and, in all likelihood will never meet, and I can only speculate about their lives. What made them interested in gender studies or the fall of the Roman Empire? Are they checking out a book for a paper or for sheer personal interest? In a world of strangers, the hold shelves create a moment of intimacy, however fleeting or whimsical or pointless that moment might be.

Occasionally, I might recognize one or two big-name professors on those hold receipts. The hold shelves become exciting because they are a tableau of scholarship in progress. They literally contain the footnotes which will appear in a Pulitzer Prize-winning book five years down the road, or the parenthetical citations which will be in the next Nobel Prize-winning paper. Compared to the hold shelves, the “Hot off the Press” section of the Yale bookstore is an antique shop.

Yet the hold shelves also possess an essentially democratic quality. A book reserved for an endowed professor can lie right next to a book reserved for an undergraduate; the only discriminant is the alphabetical order of one’s last name. In this sense, the hold shelves represent what the academy aspires to be: a space defined by ideas rather than hierarchy or pedigree.

Having said that, the neatness of the hold shelves belies the many inequities that persist at Yale. On the one hand, they make me grateful for the incredible array of staff who keep the library and the university running. The work we do at Yale may be intellectually demanding, but it is no more or less significant that the labor required to keep an institution of this size operational.

On the other hand, the hold shelves also remind me of the need to advocate for these workers. Be it the student worker trying to pay her student income contribution or an ITS employee at risk of being laid off, we owe it to them to listen to their concerns.

But mostly, I find the hold shelves reassuring. During the long nights at Sterling, when I sometimes feel completely, utterly alone, the hold shelves whisper to me that somewhere in the history of human knowledge, someone must have confronted the same academic or personal problem I now face. Above all, the hold shelves give me hope: However obscure, the story I am writing may one day be read.

Jun Yan Chua is a sophomore in Saybrook College. His column runs on alternate Fridays. Contact him at junyan.chua@yale.edu .