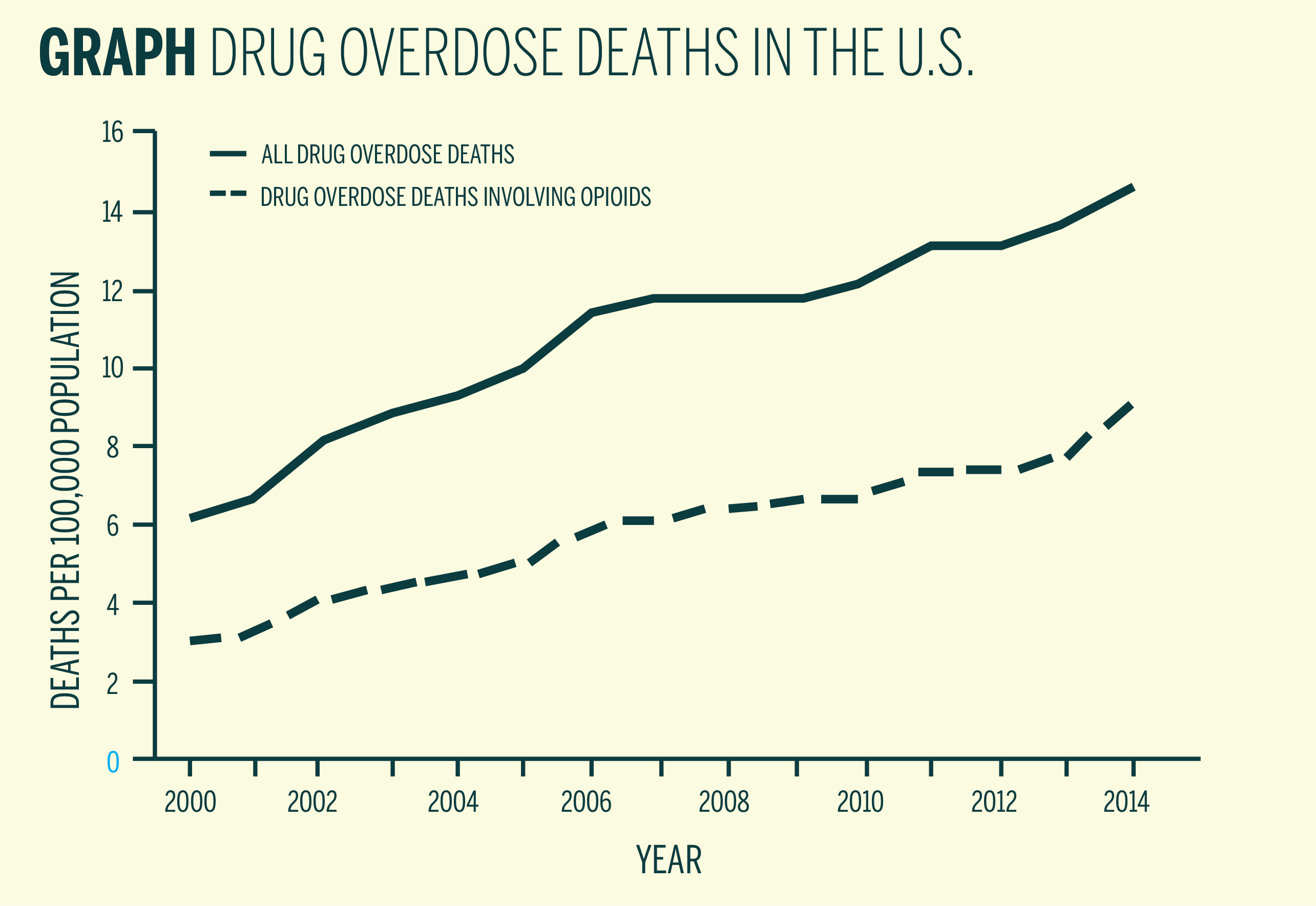

A scientific advisory panel recommended in January that the Food and Drug Administration approve Probuphine, an implant that slowly releases the prescription drug buprenorphine, as a treatment for patients with opioid-abuse disorders. The panel’s recommendation comes in the midst of what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls a national drug overdose “epidemic,” with opioid overdose death rates reaching 9.0 per 100,000 in 2014. Approval of the Probuphine implant has the potential to help cities across the country, including New Haven, which had a total of 84 heroin-related drug overdose deaths from January to September 2015.

Developed by the New Jersey-based Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, the Probuphine implant is inserted under the skin in the upper arm and slowly releases buprenorphine — the most commonly used medication to treat opioid-dependence — to help dependent patients maintain sobriety for six months. If approved, Probuphine would be the first FDA-approved implant and longest-acting treatment for opioid addiction. Although the panel voted to recommend that the FDA approve Probuphine, the decision was far from unanimous. Some members of the panel expressed concerns about proper dosing and the dangers of making any changes to stable patients’ treatment regimens. However, several national and Yale-affiliated addiction researchers said Probuphine, as a rehabilitative treatment, can have several advantages for opioid abusers, including consistent controlled dosing and easy administration. The FDA is scheduled to make a decision by May 2016.

“Medication offers the best chance for people with opioid addiction to sustain recovery, but … the few, current options are not enough to address the tremendous needs of the vast population dealing with this complex disease,” said Braeburn Pharmaceuticals President and CEO Behshad Sheldon in a January press release. In the release, Titan Pharmaceuticals President and CEO Sunil Bhonsle said that “new treatment options for the millions of patients and their families suffering from opioid addiction are desperately needed.”

Richard Rosenthal, medical director of addiction psychiatry at the Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System, has been working on addiction research for decades, contributing to two published randomized clinical trials of buprenorphine implants. These trials demonstrated that buprenorphine implant treatment was superior to a placebo and not inferior to sublingual buprenorphine, a common form of buprenorphine administration in which tablets are placed under the tongue.

Rosenthal emphasized that while sublingual buprenorphine can be a lifesaving treatment, the buprenorphine implant Probuphine offers additional benefits for many patients. With the implant, patients cannot miss doses — a common mistake that often leads to drug cravings — and there is no chance of children accidentally ingesting the drug. It would also be very difficult for patients to share or sell their buprenorphine, he said.

“The bottom line is that [buprenorphine] works,” as a treatment for patients with opioid-abuse disorders, Rosenthal said. “Relapse rates are very high” for patients with opioid-abuse disorders, he noted, and patients receiving medical treatment have higher rates of successfully maintaining long-term sobriety.

Brent Moore, a researcher at the Yale School of Medicine who was not affiliated with the scientific advisory panel that recommended Probuphine’s approval, said that buprenorphine maintains relatively stable, consistent levels in blood when taken regularly, which is advantageous in controlling drug cravings. He added that unlike methadone treatment — in which patients must obtain daily methadone doses in a clinic, a practice that can carry stigma — buprenorphine can be taken at home.

Moore noted that for the vast majority of opioid-dependent patients, treatment with medication was markedly more effective than abstinence-based rehabilitation methods. He said that for patients who had regularly used opioids for more than a year, withholding medications like buprenorphine or methadone is “almost borderline unethical.”

Moore noted that preventing people from using opioids for the first time could help curb the rising overdose rates. However, he said that for those who are already dependent on opioids, “buprenorphine can help people with long-term addiction feel normal and help them function.”

The panel’s recommendation comes during a time of rapidly increasing overdose rates, the majority of which are caused by various prescription and illicit opioid drugs. A January Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report from the CDC stated that the United States is “experiencing an epidemic of drug overdose (poisoning) deaths.” According to the report, opioid overdose deaths have risen across all racial groups and genders, going from 7.9 per 100,000 in 2013 to 9.0 per 100,000 in 2014 — a 14 percent increase in just one year. In the past three years, heroin overdoses have more than tripled.

“The prescription opioid epidemic is driving the heroin epidemic,” Rosenthal noted. “The largest component of people who use heroin started out with prescription pain medications.” Because prescription pain medications are usually much more expensive than heroin, people who have become dependent on prescribed opiates have an incentive to switch over to heroin, he added.

According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, heroin has become increasingly available in recent years and is a particularly high threat in the Northeast. Because heroin’s purity has increased, it can more easily be snorted or smoked, methods which are more appealing to new users, who are more likely to be averse to injecting drugs intravenously, according to the National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary released by the DEA in April 2015.

Even though the population of heroin users is smaller than the populations of other illicit drug users, heroin use is growing at a faster rate and is much more likely to cause fatal overdose than other drugs, the DEA report noted. Since opioids slow users’ respiratory rates and can induce vomiting, users can suffocate quickly, the DEA report noted. According to the report, in response to increasing rates of fatal opioid-related overdoses, many law enforcement agencies are training officers, who are often the first responders in overdose cases, to administer naloxone, a fast-acting drug that can reverse the effects of opioid overdose.

However, even as overdose rates have skyrocketed, public opinion has become increasingly accepting of drug addiction as a brain disease. Rosenthal indicated that the brain chemistry of an addict differs from that of a non-substance abusing person.

“[An addicted patient’s] biology — especially their brain biology — has changed,” Moore said. “How they respond to reinforcing stimuli is different” from how non-drug dependent people respond to reinforcing stimuli. Both Moore and Rosenthal emphasized that even though cultural attitudes toward addiction have shifted significantly, drug dependency still carries stigma.

Kevin Garcia ’16 and Jack Zakrzewski ’16 know firsthand the gravity of opioid-related drug overdoses. As EMTs in New Haven, both Garcia and Zakrzewski have responded to overdose calls. Garcia noted that some overdoses occurred in unexpected areas, such as nicer, suburban neighborhoods, a reflection of the changing demographics of drug users. Hallmarks of opioid overdoses include slowed or absent breathing, pinpoint pupils, slowed pulse and loss of consciousness, according to Garcia. “I’ve been [called to] numerous fatal overdoses,” he said.

Zakrzewski, who said he has seen many drug and alcohol related problems while working, noted that addiction’s impact extended beyond the users themselves. He said he found the effects of substance abuse are most painful in the context of families, especially “when it’s the parents calling for the kid or the kid calling for the parents,” and cited a case where a school-aged child overdosed after accidentally ingesting some type of opiate drug that belonged to a parent. Both Zakrzewski and Garcia said they view addiction primarily as a brain disease.

Though the FDA often follows the recommendation of the advisory panel, it is not required to do so.

In the United States, prescriptions for opioid drugs have quadrupled since 1999.

Correction, March 14: A previous version of this article misstated Richard Rosenthal’s title. In fact, he is the medical director of addiction psychiatry at the Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System.