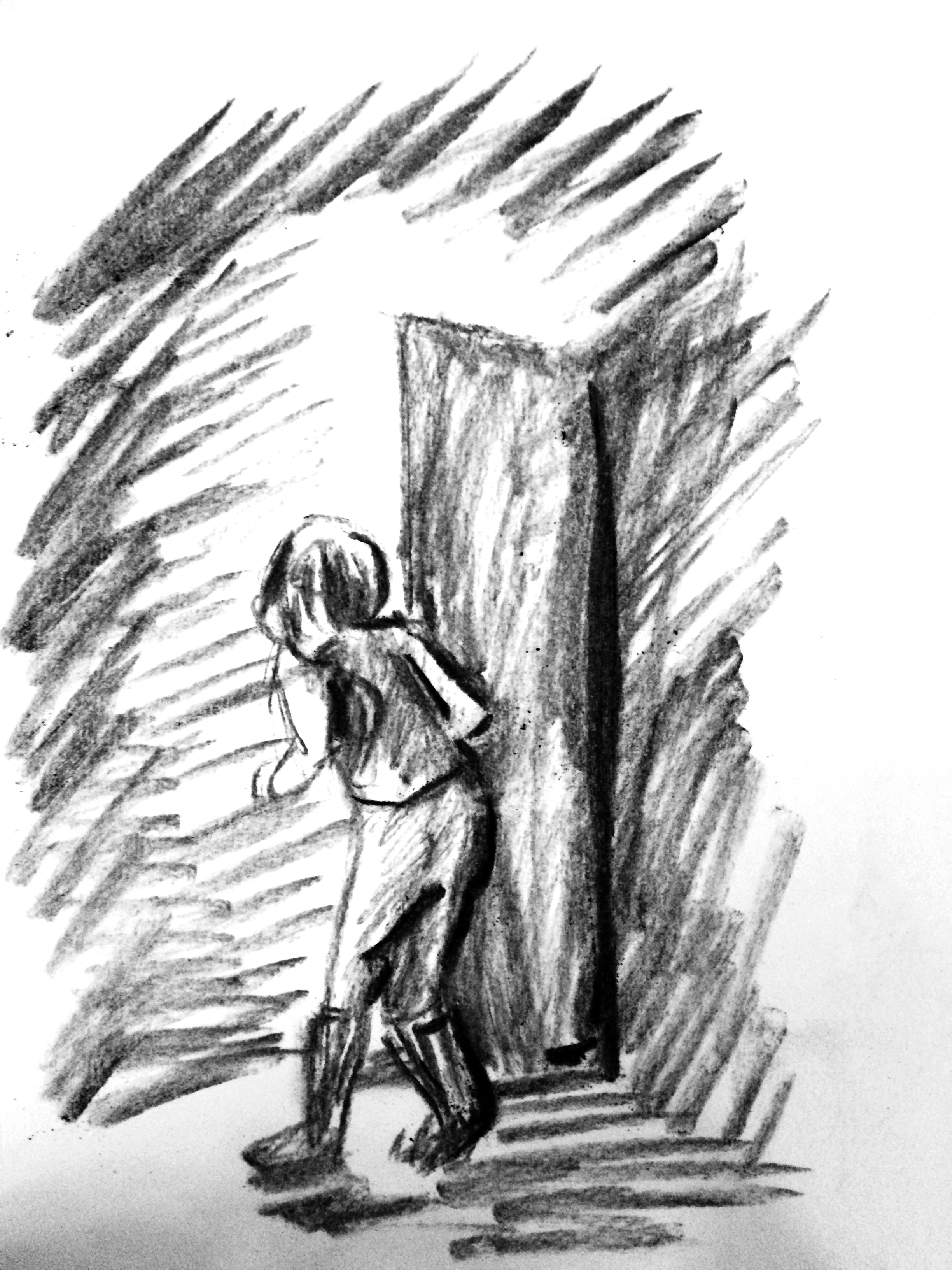

Way up entryway B of Davenport College, past the lone, gnawed carrot that’s found home under the second-floor radiator, up the narrow staircase where one starts to feel her presence forbidden, through an attic flecked healthily with detritus, its ceiling just short enough to strain a neck, lies a white door marked in thin pencil: “The Place.” From outside, Davenport’s cupola stands clean and decorative, like a groom on a cake. Inside there are three tiers of garbage.

“The Place’s” floor lies open like an autopsy; its boards uproot to soft pink bellies of insulation, its brick wall crumbles to a halt, its struts and buttresses rot like dead guts. Up a rusty ladder is the lower cupola, a small cement landing with just room enough to sit. On the floor I count 17 bum ends of joints, 13 cigarette butts, two Budweiser cans (lightly dented), two wine bottles aligned opposite, two Torpedo IPA bottles aligned opposite, the calcified remnants of a soft pretzel and a whopping 34 Black and Mild filters — wood-tip wine-flavored, according to the five empty boxes, and anyone who knows anything about Black and Milds, a lesson I learned from Javi Brennan sophomore year of high school. The place is a five-star stoner den, “a little treasure,” says Darren Watsky, who visited four times his freshman year. Watsky found out about the cupola from a friend who’d heard it from a friend in his cello group. Word of mouth has kept visitors coming and leaving their names for the past couple decades (the oldest date I find listed is “Steven M + Jonathan Z, Sept ’90”). As I climb another ancient ladder into the upper cupola, a closet-sized space that is mostly window, the names multiply.

“Morgan was here”

“Patrick Ng was here”

“Rima, Global Affairs, Age: 21, Interests: Queefing”

“Laura Martinez BF ’14 fuck yeah! <3 I love everyone who loves ME!”

Martinez, who has lived in Thailand since graduating, visited the cupola senior year with a couple of friends from dance. “We were looking to do some bucket-list things.” As to her note: “I was feeling particularly gutsy about the fact that I was leaving and Yale could do nothing to me.”

Another name reads “2013 Stovetop Mike,” the only name I recognize — a thick-fingered junior with a ponytail and bolo tie who’d insisted I would “find my people eventually” after I’d fretted over starched, white-socked Yalies upon my first visit here in high school. We haven’t spoken of the interaction since.

“Yeah, I’ve been up there a few times with my friend. We’d just hang up there and smoke. One time we had a Danksgiving,” (an event that did not take place on or near Thanksgiving) “We smoked a lot of j’s. It was dope.”

When I ask Stovetop Mike if he was put off by the archaeological dig of trash, he responds, “I’m a disgusting, shitty human. I’ve slept on roofs for the past three nights. It takes a lot to gross me out.”

“The revolution will never be televised,” wrote Jamie Singer ’15, an alum who is also accustomed to sleeping on roofs. “It’s a funny story,” he says when I ask him about the cupola, “sophomore year I was actually living up there for a bit.” Singer, shafted by a bad housing draw, landed in a suite with a roommate “who shall not be named,” he says with a laugh. “For a while I was sleeping in a different suite every night. Then one day I found that little tower with my friend Tia. I ended up spending the night there.” Singer dragged a couch (now gone) up to the first floor and slept there for a couple months before Yale Outdoors found someone had been living out of their storage closet in the lower cupola — Singer had borrowed a tent and sleeping bag.

“They changed the locks so I couldn’t get back in,” Singer says, though he was never caught. I ask why he wrote his name. He says immediately, “It’s the same reason you write your name anywhere, to leave a piece of yourself behind for the next generation.”

Standing in the upper cupola at night, the whole of Yale strung out like tea lights, there is certainly the feeling that you’ve conquered something, that you’ve bested Yale in some indelible way. Truth be told, the view is better in the daytime, though everything looks farther away. I watch a pack of muscled boys play touch football with Davenport Dean Ryan Brasseaux and his son. They catch effortless passes across the neat summer grass. They have short hair and clean smiles and the kind of sweat that is somehow pretty. From up here you can see the other disheveled Yale roofs — some forgotten scaffolding on top of Sterling, a great dent in J. Press where various weather has gummed into a dense, black pool. The windows of the cupola are painted shut.

“Before I came here I thought everyone loved exploring. That’s just what we used to do at home,” says Watsky, who showed me the cupola for the first time last week. “This place feels nostalgic.” I agree, rolling around an old Black and Mild with my toe. He insists on being quiet, though I think he’s being overly cautious. The stairwell door is taped open, “The Place’s” door is unlocked, there are sturdy ladders resting from floor to floor of the cupola that are clearly not there for maintenance men. Watsky explains that a group of athletes living in the suite below complained last year about kids smoking in the cupola, an activity the dean turns a blind eye to so long as people aren’t disruptive. It’s unclear if graffiti in the cupola is an act of roof-hopping, weed-smoking rebellion or a sanctioned Yale activity, a poorly kept secret for those who feel more at home in piles of Ricola wrappers than on freshly rolled lawns. The walls comfort rather than announce:

“I was here”

“Me too”