Yale’s two graduate and professional student assemblies embarked on a new campaign last semester to secure child care subsidies for student-parents at the University, lobbying administrators and collecting new data that illustrates the difficulties of raising children on a meager paycheck. But while the dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences has pledged to make child care her top fundraising priority, securing subsidies for student parents in the professional schools may prove significantly more difficult.

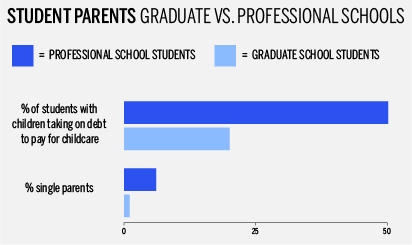

The challenges faced by graduate-student parents and student parents in the professional schools are fundamentally different, according to representatives from the Graduate Student Assembly and the Graduate and Professional Student Senate, the organizations spearheading the push for child care subsidies. The graduate school offers free health insurance to the children of graduate-student parents, but that benefit is not available to student parents in the professional schools, who are estimated to make up about 4 percent of the professional school population. According to new data gathered by the GPSS, about 6 percent of professional school student parents are single parents, compared to 1 percent of graduate-student parents.

But while Graduate School Dean Lynn Cooley has vowed to address the child care needs of graduate-student parents, in the professional schools, the patchwork of divergent fundraising priorities and financial aid programs has posed a significant hurdle to the ongoing campaign to provide subsidies to student parents who are not pursuing a Ph.D.

“In practice, this is going to be very, very difficult — finding the same kind of funding across graduate and professional school students,” said Wendy Xiao MED ’17, who chairs the Facilities and Health Care committee of the GSA. “Getting funding for all graduate-student parents is a lot more straightforward than for all professional school parents.”

The GPSS and GSA have spent months lobbying Cooley for child care subsidies for graduate-student parents. But securing the same support for student parents in the professional schools may require a Herculean lobbying effort stretching across the dozen schools, which all have different budgetary aims and priorities.

The groups met with Cooley two weeks ago to present data they gathered last semester on the child care issue. The data — which the groups collected through a survey that attracted about 230 respondents — indicates that roughly 50 percent of professional-school-student parents have taken on debt to pay for child care, at a median annual rate of $12,000 per year, or roughly 40 percent of their median annual income. Only 20 percent of graduate-student parents take on debt, at a rate of $7,000 per year.

“A lot of professional school parents are putting themselves in debt to go to school in the first place,” Xiao said. “The graduate school families have a stipend, and some of them still are taking on debt to pay for child care. But it is, of course, less than tuition and child care.”

GPSS President Elizabeth Mo GRD ’18 said her organization has raised concerns with University administrators about child care funding for professional school students. The group is still working to determine whether funding for subsidies would have to come from each individual school or whether it could be channeled from a more centralized source, such as the Office of the Provost.

The Law School and the School of Medicine, the two professional schools with the largest student populations, have affiliated day care centers that give priority to student parents and faculty associated with those schools. But the two centers, which have only a limited number of slots, both cost in the region of $1,500 per month, more than many professional school parents feel they can afford. The cheapest of Yale’s seven privately owned but University-affiliated child care centers costs more than $1,300 per month, and the only Yale-affiliated center that subsidizes tuition costs for low-income student parents has just 60 spots for children and provides preschool services rather than infant and toddler care, which is significantly more expensive. Yale is one of just three Ivy League schools that does not offer any kind of child care subsidy.

“As a matter of fairness, Yale should standardize its aid supporting the children of student parents across all graduate and professional schools,” said Ian McConnell MED ’17, a student parent in the medical school. “Yale could do much more to support graduate student families by providing incremental aid and health insurance subsidies in line with the true costs of raising a child today.”

Another parent in the medical school, who asked to remain anonymous to speak candidly about her personal experiences, said that at least three student families in the professional schools are on Medicaid and that the University should extend health care benefits to student parents outside the graduate school.

Still, student parents in some of the professional schools — especially the medical school, law school and School of Management — have a high future earning potential and can afford to take on more debt than their counterparts in the graduate school. Last semester, the seemingly bright financial prospects of some professional-school student parents became a source of consternation for graduate-student parents who were competing with them for child care funding from the GPSS, which offered modest child care subsidies to 20 eligible student families. The group was able to fund only about 9 percent of the total number of applicants, on the basis of demonstrated financial need.

Anna Jurkevics GRD ’16 said she and her husband, who is also a graduate student, were shocked to see their application turned down.

“We’re like the poorest people we know,” she said.

Jurkevics added that she was concerned that professional-school student parents had an unfair advantage in the application process because their high debt load made them appear poorer on paper than their peers in the graduate school.

“There should be two separate funds entirely: one for professional students and one for GSAS students,” Jurkevics said. “We have different future earning potentials that affect our ability to take on debt now, so we need to be considered separately for child care subsidies.”

But Mo, who said she no longer has access to the school-by-school breakdown of the students who received awards, noted that the applicants from the professional schools included students from the School of Drama and School of Art, who have significantly lower future earning potentials than medical and business students.

“I am wary of saying that a professional student has a higher earning potential than a graduate student,” Mo said.

Xiao said it would be unfair to take future earning potential into account even when evaluating the financial need of student parents in the medical school or law school.

“Who are we to decide who will be making more money in the future?” she said. “That doesn’t mean that the families aren’t struggling right now, that they’re not in need right now.”

The GSA plans to release a report on the child care issue sometime before the end of the spring semester.

Paddy Gavin contributed reporting.