Calling for a structural transformation of the state of Connecticut’s budget, Gov. Dannel Malloy laid out a proposal Wednesday that would cut thousands of workers from the state’s payroll and impose a new philosophy on the state’s budgeting process.

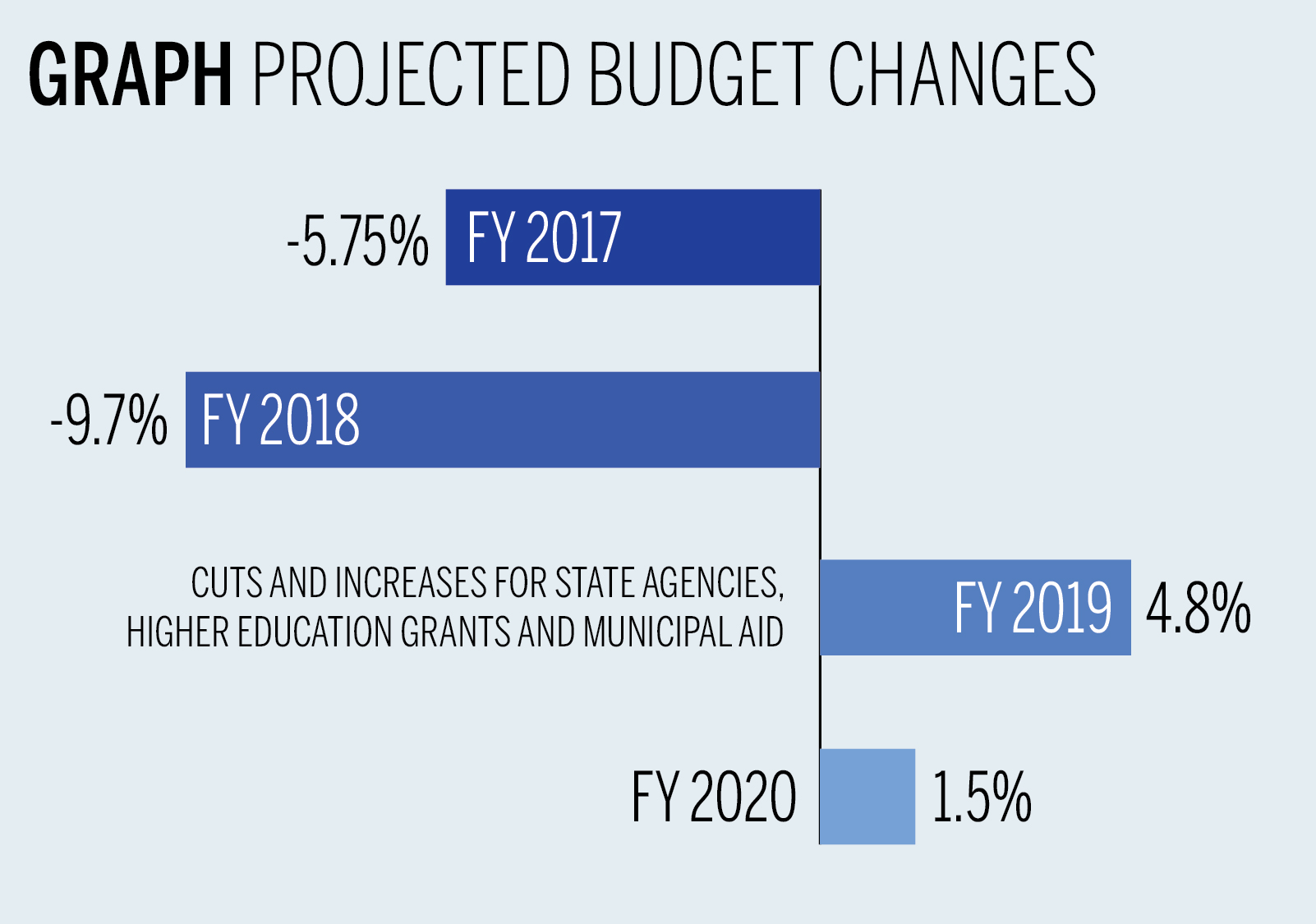

In his speech to a joint session of the General Assembly, Malloy urged legislators to pass an enforceable spending cap to force the state to “live within its means.” Malloy said his new budget for fiscal year 2017 — which would enact $570 million in cuts to bring the year’s projected spending down to $18.1 billion — will be the first step in the state’s adjustment to a new economic reality. But though the budget does not bring any new tax increases, the across-the-board cuts Malloy has proposed will likely be a tough pill for Connecticut residents to swallow.

“Connecticut is not going back to that prerecession reality,” Malloy said, referring to an era in which state spending could rise more freely without obvious consequence. “It just doesn’t exist anymore. The people of Connecticut know it — they’ve accepted it — and so must their government.”

Malloy’s proposed budget for FY17 is technically a set of revisions to the second half of the biennial budget the General Assembly passed last year. Malloy’s cuts will need to be approved by the General Assembly in the session that opened Wednesday afternoon before they can become law.

A constitutional spending cap that limits year-by-year growth of state spending was first passed by Connecticut voters in 1992, but legislators have never passed a bill that would give the state government the ability to enforce the cap.

The cap has been traditionally supported by Republicans in Hartford. Senate Minority Leader Len Fasano ’81, R-North Haven renewed the call for an enforcement mechanism in a New Haven Register op-ed last November.

In a presentation to lawmakers before Malloy’s speech, State Budget Chief Benjamin Barnes said the budget cuts would necessitate large reductions in the state’s workforce, either through layoffs or attrition.

“I cannot hide that the scale of reduction that we propose will result in many fewer state employees, and it is an open question as to how much of that reduction will be accomplished through attrition and how much will accomplished through other means,” he said. “But it is likely to be a combination of both.”

Barnes said the state will need to reduce spending on agency operations by at least 15 percent over the next two years, adding that the means of reaching those “deep reductions” will be discussed with legislators.

In remarks to the state House of Representatives, House Speaker Brendan Sharkey, D-Hamden, said Connecticut’s difficulties are the product of the state’s slow recovery from the Great Recession and ensuing economic downturn.

Though unemployment has fallen since its peak five years ago, he said, incomes have stagnated, depleting Connecticut’s tax base and depriving the state of crucial revenue.

The data backs up Sharkey’s claim. Barnes noted in his presentation that employment growth from 2011 to 2015 was roughly the same as it was between 2004 and 2008. But he said average annual wages grew 16.9 percent in the latter period as opposed to 5.6 percent in the former.

Malloy’s proposals met a negative response before he even spoke to the General Assembly. In an interview with CT-N Wednesday morning, Fasano criticized Malloy for his nontraditional approach to the FY17 budget.

In previous years, Fasano said, the governor has presented the General Assembly with a line-by-line budget, allowing legislators to make cuts on a line-item basis. This year, however, Malloy drafted a block-grant budget Fasano described as the product of mismanagement by the governor’s administration.

“Now, we’ve abrogated our responsibility under the governor’s plan,” Fasano said. “This has never happened before; I don’t agree with the governor’s form of budgeting, and I think it’s because we’re so far in the hole.”

Malloy’s budget was also criticized by a group that will prove crucial for the future of the state’s finances: public labor unions. In a statement released just after Malloy finished his speech, the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition — which represents all 45,000 state workers — said the budget’s proposed cuts could prove disastrous.

Xavier Gordon, president of Council 4 AFSCME, the largest trade union of public employees in the U.S., said the budget represents the political mantra that “politicians won’t have the guts to ask the rich to pay their taxes during an election year.” In the SEBAC release, he called on Connecticut’s legislators to raise taxes on high earners to alleviate income inequality and relieve working-class residents of their high tax burden.

Malloy said he plans on negotiating with SEBAC and the teachers’ unions to reach a solution in the coming months. Those negotiations, he said, will be based on “what we can afford, not what we previously spent.”

Malloy can claim one victory, however: Barnes said the governor has no plans to tap into the state’s rainy-day fund to balance the budget. Tapping into the fund at the current moment, Barnes said, would be an “awful” idea.