Twenty-five. That’s how many texts I’ve sent so far today. I text about psets and dinner plans. I text Hey and How’s it going? and occasionally Let’s talk about this in person. Sending these messages is reflexive; texting is a convenient and integral part of my life at Yale. But I haven’t always been so wedded to technology.

I’m from Japan. If you saw me on Old Campus or racing down the corridor in WLH, you wouldn’t know this. Most people don’t until I tell them. And, in truth, I’m not Japanese. I was born and raised in Tokyo but am pretty obtrusively foreign. Back home, I never struggled for breathing room on the subway, even at the peak of rush hour; at 5-foot-9, all I saw were the tops of heads. Sometimes I would hear the passengers talk about me in Japanese — “That girl is so tall,” “Look how light her hair is” — thinking I didn’t understand. And yet, though I have a U.S. passport and am not Japanese, I am not wholly American.

In high school, my friends and I talked about “Americans” like they weren’t us. (Most of us, though admittedly not all, had at least one parent who had been raised stateside.) Americans couldn’t understand the metric system, we joked. They couldn’t handle their liquor, or walk places, and they really couldn’t get off of their damn phones. This was a big one. Whether this criticism was unique to my immediate circle of friends or to my strange, international, purportedly “American” school, I’m not sure. I don’t want to paint my expatriate upbringing as some screen-free utopia. It wasn’t. I spent a lot of time taking selfies on Snapchat and stalking people (and by people I mean of the my-friend’s-third-cousin’s-fiancé variety) on Facebook and Instagram.

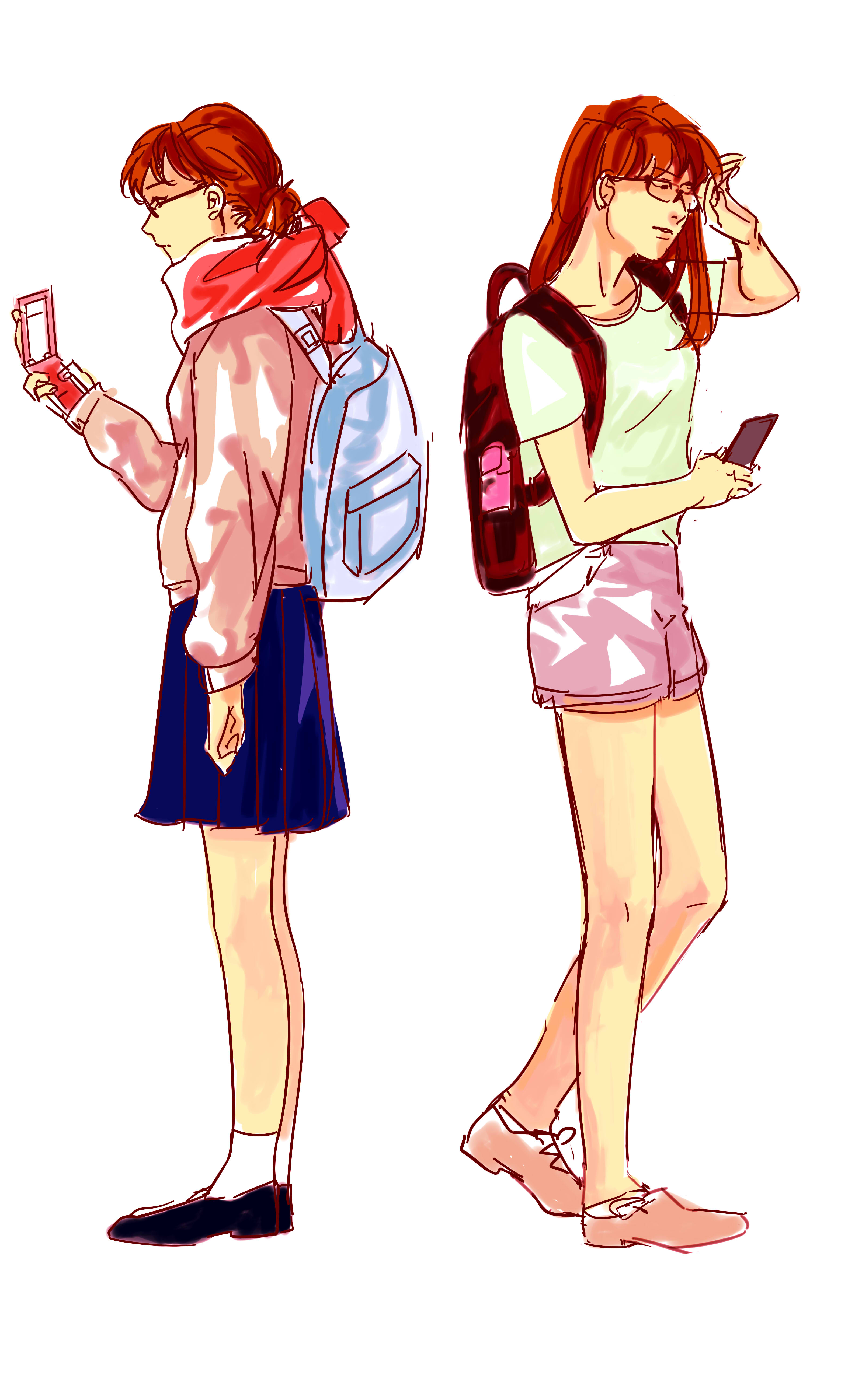

But there was always something different about how we understood our actions and how we understood those of Americans. We put our phones away when we ate meals. We consulted maps for directions. For the most part, we really didn’t text. This was my reality and I was proud of it.

Then I came to college. Now, for the first time, I am living in America. Land of the free, land of chattiness, land of open spaces and sandwiches the size of my torso. And I am one of the Americans, online and with a phone charger perpetually in hand.

To my surprise, when I arrived here, I shrugged off my former identity as something of a Luddite without sentimentality. I did not eulogize my trusty paper planner when I abandoned it two weeks into September in favor of a GCal. I am not squeamish about leaving my phone on the table during a meal. I eagerly exchange numbers with people, and I actually make use of them.

Part of it is necessity. This is college! There are a thousand things happening at any given time — talks, office hours, hangouts, meals — and it’s these activities that make being here worthwhile. To take a page out of Aerosmith’s book, I don’t want to miss a thing. None of us do. Even my born-and-bred American friends have remarked that they’ve used their phones more since starting school than they ever did at home.

My phone has proved integral to my life on and off campus. Just last week, I had one of my best and most intimate conversations in the last few months with a friend at school on the other side of the country. The hoops we had to jump through to plan our Skype date were comical; she Snapchatted me, I texted her, we ended up settling on a date and time over Facebook chat. It was an aggravating process, but once we were in the same place — figuratively, at least — the distance vanished.

If you’re a millennial — or you have parents who are obsessed with reading about millennials — you’ve probably read something about how technology is destroying us. It’s one of those topics that is both persistently hot-button and totally hackneyed. Beauty bloggers write posts about unplugging for the day and seeing the world anew. Friends discuss deleting their Facebook pages, how liberated they felt. There are more than 52 million search results for “the problem with smartphones” online (I know this because I googled “the problem with smartphones” on my smartphone). The concern that technology is gnawing away at life as we know it has been present since the advent of the printing press.

A recent example is the New York Times op-ed “Stop Googling. Let’s Talk.” The piece, written by MIT professor Sherry Turkle, features many of the criticisms of cell-phone culture and connectivity that we are all familiar with. Turkle writes of the “sense of loss” kids these days feel in their day-to-day interactions as a result of the ubiquitous iPhone. Apparently, “the mere presence of a phone on the table between [two people] or in the periphery of their vision changes both what they talk about and the degree of connection they feel.”

None of this read as terribly new or exciting, but one of Turkle’s findings genuinely unnerved me. She writes of a University of Michigan compilation of 72 different studies conducted over a 30-year period. The discovery? “A 40 percent decline in empathy among college students, with most of the decline taking place after 2000.” This conclusion stands on the shoulders of earlier psychological studies showing that people are “inextricably linked to their social environment and to those around them.”

According to Turkle, “Research is catching up with our intuitions” that smartphone use is becoming a hindrance to interpersonal interactions. She says the question we face is not one of whether or not to use our phones, but of how to use them intentionally, rather than indiscriminately. I agree. That said, she uses examples of children who cannot read facial expressions or social cues to prove the correlation between the advent of technology and our empathetic faculties — this is a little alarmist. I don’t think a screen can or will ever replace the touch of a hand or the sound of someone breathing next to you.

Technology serves as a conduit for empathy, rather than an obstacle to it. As with my Skype date last week, seeing the familiar expressions of my friend as she spoke made me feel incredibly close to her. Technology also gives you a comforting dose of social assurance; you always know when you’re on someone’s mind. Every time someone sends me a link to a Comedy Central clip, or tags me in an Instagram of a porcupine being tickled (I’m a sucker for porcupines), I know they’re thinking of me. This goes both ways; I love reaching out to people just as much as I love being reached out to. And isn’t that what empathy is all about?

Intentionality is valuable, yes, and I intend to keep it in mind. But I also intend to use my phone as I see fit. Sometimes that means replying to a text message right when I get it. Sometimes that means checking my email 18 times in an hour. Sometimes that means taking 15 minutes out of my frenetic and jam-packed day to play Internet solitaire or look at food porn on Instagram. I don’t have the 90 minutes to decompress by watching a movie, but I do have the three required to unlock the next level of Candy Crush. These things have become important to me, and I intend to keep them in my life.

Part of me questions the validity of this continued debate because, let’s face it, cell phones aren’t going anywhere. I refuse to believe that we, the digital natives, are any more robotic and apathetic than those who came before us. Today, a life best lived is arguably one lived with a smartphone in hand. Let’s be purposeful. Let’s also stop bemoaning them. There are more important messages awaiting our response.