In September of her sophomore year, Yamile Lozano ’17 received a letter threatening her with forced withdrawal from Yale College.

After some initial panic, Lozano figured out what the problem was: She owed Yale $2,000. The daughter of formerly undocumented immigrants, Lozano came to Yale under the impression she would receive a completely free education. What she found was a situation far more complex.

The total cost of attendance at Yale for the 2015–16 school year is $65,725. Lozano is one of roughly 2,800 Yale students — or 52 percent of the undergraduate population — receiving need-based financial aid from the university. Families earning between $65,000 and $200,000 are responsible for what is known as the parental contribution: a percentage of their yearly income toward their child’s Yale education. This percentage, determined by Student Financial Services, works on a sliding scale as income increases. Families with usual assets whose total gross income is less than $65,000 are not expected to make any financial contribution towards tuition. For these families, Yale declares unequivocally that 100 percent of the total cost of attendance will be financed with a Yale Financial Aid Award.

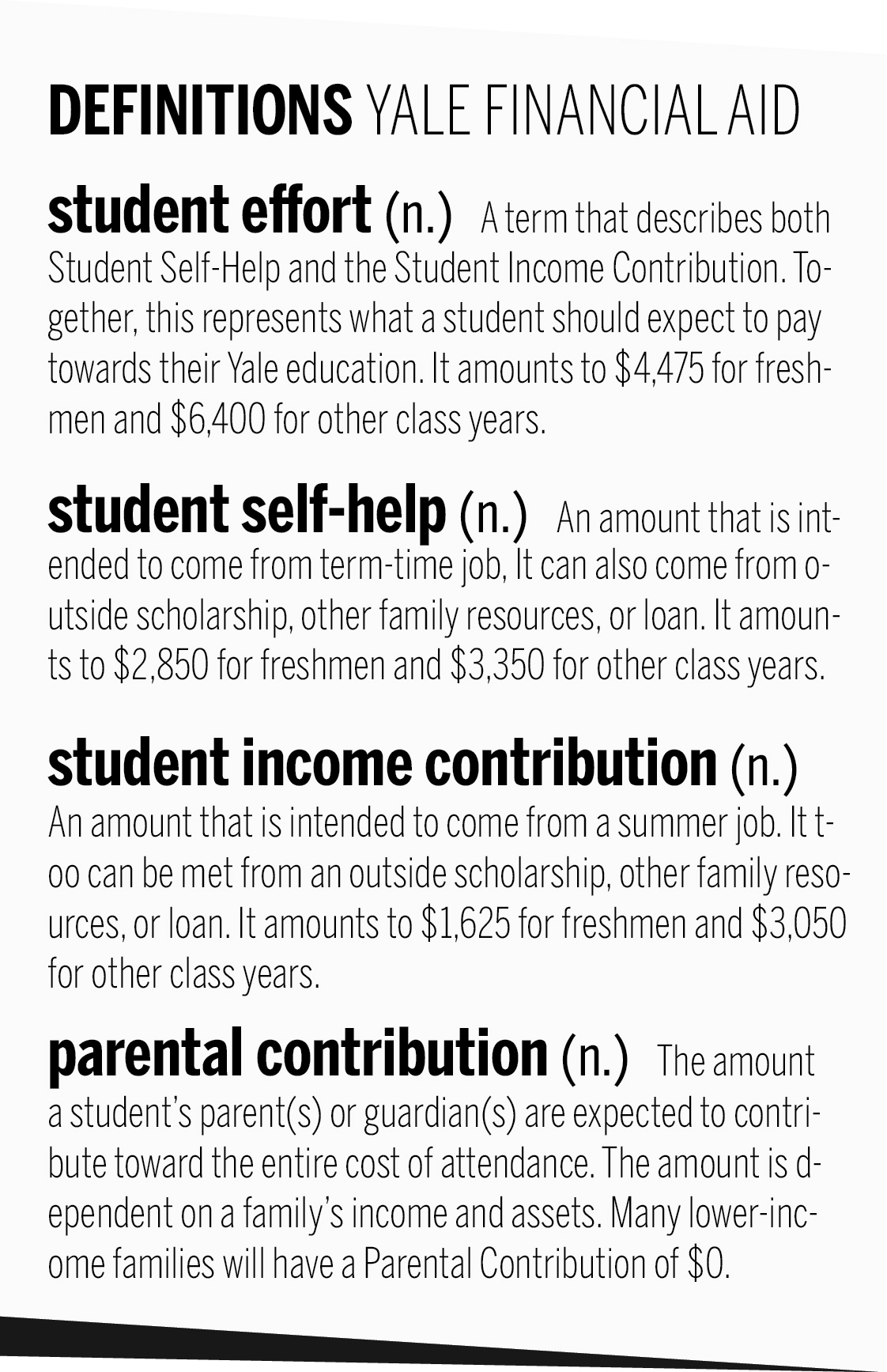

However, students must still pay the “student effort” portion of the cost. This is comprised of “student self-help,” an amount intended to come from term-time work and used for books, laundry and other miscellaneous costs, and a “student income contribution” that is intended to derive from summer work and is paid to the University. The total student effort represents what a student should expect to pay toward her or his Yale education, and amounts to $4,475 for freshmen and $6,400 for all other class years.

Because Lozano was notified before arriving at Yale that her expected family contribution was zero, she inferred that she too would not have to pay anything, and was unaware of the student effort payment. Outside scholarships covered her needs during her freshman year, and in the following summer she participated in the Science, Technology and Research Scholars Program, administered by the Yale College Dean’s Office. The program provides a total stipend of $2,500 and also covers participants’ SIC. Unbeknownst to Lozano, her student effort portion had been covered the entirety of her freshman year. Shortly after receiving the letter demanding payment during her sophomore year, Lozano was finally forced to confront the student effort payment. If she couldn’t meet it, she would have to withdraw from Yale.

Ups and Downs

Ups and Downs

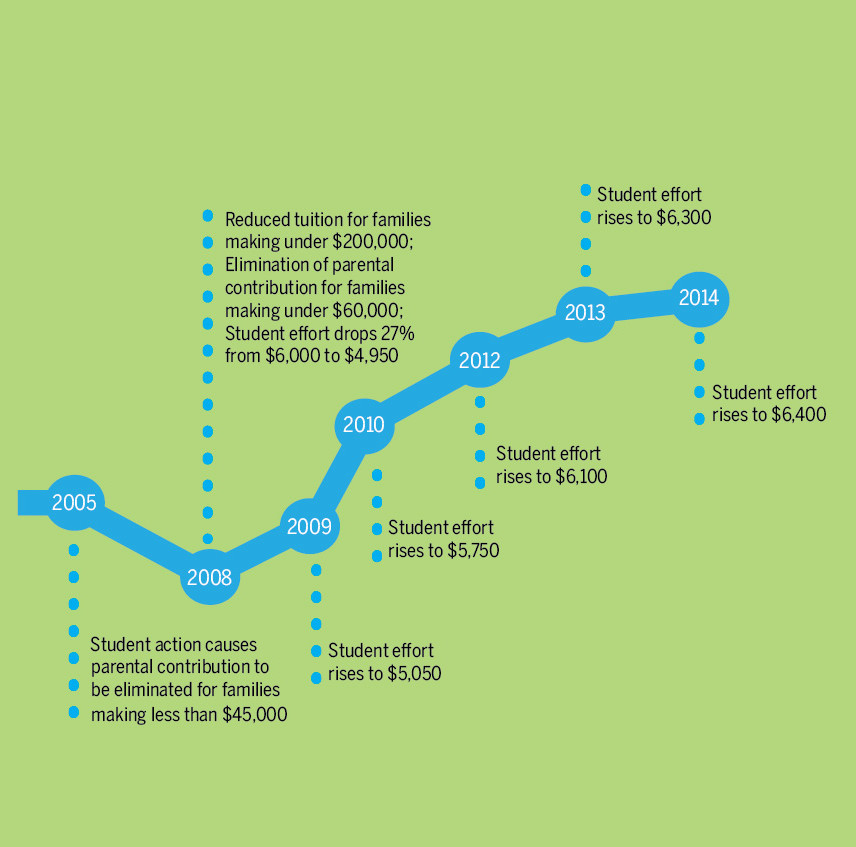

On Feb. 24, 2005, 15 Yale students staged a sit-in at the Admissions Office to demand reforms in the college’s financial aid policies. The students, bolstered by around 150 protesters outside, occupied the building for over eight hours until New Haven police officers and university officials shut it down. The episode, which garnered attention from national media outlets including The New York Times, prompted then-President Rick Levin to acknowledge that tuition costs were too high for low-income students. The parental contribution was then eliminated for families making less than $45,000.

A few years later, in 2008, as a result of continued student activism and protest, Yale announced it would reduce the tuition cost for families making less than $200,000. Perhaps most notably, it eradicated the parental contribution for families earning less than $60,000 annually. In that year, the student effort portion of financial aid dropped abruptly from $6,800 to $4,950, a 27 percent decrease.

The 2008–09 school year was arguably the single most affordable year in history to be a low-income student at Yale. This progressive spirit quickly disintegrated, however, and the student effort saw incremental surges each year. In 2009, student effort increased from $4,950 to $5,050. By 2010, it surged to $5,750. In 2012, costs rose to $6,100. The next year it was at $6,300. By 2014, it grew to $6,400.

Tyler Blackmon ‘16, a student on financial aid, former YCC member and staff columnist for the News, said the administration has been able to increase cost without significant backlash through yearly increments, rather than a large spike. He added that because undergraduates are transient students, they have little memory of what occurred in 2005 or 2008.

“That’s what Yale relies on,” he said. “It knows it’ll outlast students.”

Back in 2008, Levin stated that all students should be able to experience Yale without anxiety over jobs or debt.

“Our new financial aid package makes this aspiration a reality,” he said.

But since 2008, the total student effort has increased by over 37 percent — is this aspiration still a reality?

Working to Live

“It’s impossible to pay.” Jackson Stallings ‘17 said.

Stallings, a tight end on the football team, referred to the difficulty of paying the student effort while playing on a varsity athletics team. He noted that while the NCAA mandates athletes play no more than 20 hours a week, with travel time, meetings without coaches, health treatment and independent exercise, football players spend closer to 40 hours a week on the sport.

As a result, Stallings doesn’t have enough time for a student job during the football season. He picks up one up during the offseason, working four to six hours a week, and his mother works an extra day as a hygienist in Oklahoma City to help pay his student income contribution. He noted that some of his teammates are in worse situations; the amount they have to work in the offseason restricts their Yale experience.

Nadya Stryuk ’17, an international student from Russia, said that since she has been working since she was 14, the necessity of working seems reasonable to her and that she does not feel so passionately about student effort.

“When you’re in a poor country and you have an opportunity to go to a college, you’re ready to work and do anything to get here, so it’s not such a [problem],” she said.

But all students on financial aid interviewed pointed to two distinct Yales. In the first, students who don’t face financial pressures are free to pursue extracurriculars at will, and can spend significant amounts of time writing for a publication or singing in an a cappella group. On the other hand, students who need to complete the student effort face a far more limited Yale in which they must judge extracurriculars based on the time commitments and often forsake them altogether for student jobs.

Frances Schmiede ’17, a member of the cross country and track and field teams, echoed this sentiment. In addition to training for 12–15 hours a week, she works eight hours a week at the Yale Center for British Art’s institutional archives. She has had time to attend only one master’s tea at Yale.

She noted that the obligation to work so many hours had significantly impacted her athletics; and it took her a year and a half to adjust to the routine of work, school and training.

“It’s just so strictly regimented and there’s no time for spontaneity, which is a huge part of the undergraduate experience,” she said.

Leo Espinoza ’17, another student on financial aid, said that college is often viewed as a triangle. Out of good grades, a robust social life or enough sleep, a typical college student must choose two. According to Espinoza, this process of selection is compounded for those who need to work student jobs as they are constantly faced with opportunity costs.

While Yale limits a student to working at the most 19 hours a week, some students seek loopholes.

Aryssa Damron ’18 admitted that while the work limit is likely for the better, she often wished she could work more because she needed more money.

“I work around 19 hours a week, and sometimes I go over,” she said. “As long as you don’t do that every week, they don’t yell at you. That’s what I’ve found out.”

The Loan Road

In the fall of 2014, when Lozano realized she owed the university $2,000, she immediately investigated possible ways to pay. Despite quickly obtaining two student jobs, she still didn’t have enough money to cover her expenses. Lozano’s father, who works in construction, and her mother, a housekeeper by day and a nursing assistant at night, were unable to provide any money for her student effort. After they lost their house, Lozano noted, $2,000 was more than her family had in its savings account.

Yale’s admissions website claims the university “meets 100 percent of demonstrated need for all students” and that “no loans are ever required.” But students tell a different story. Sixteen percent of the Yale College class of 2014 — including many students not receiving financial aid — chose to take out a loan, with an average cumulative indebtedness of $14,853, according to a News op-ed written by Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Jeremiah Quinlan and Director of Financial Aid Caesar Storlazzi. Storlazzi told the News that “students can avoid borrowing because Yale does not include loans in financial aid packages.”

But Blackmon said that in his opinion, taking out a loan is not a question of “choice,” but rather a decision based on exigent financial circumstances. He argued that Yale’s promises of freedom from loans, a robust extracurricular life and great summer experiences can exist in isolation but not together.

In the 2015 op-ed, Quinlan and Storlazzi wrote that although some students may use loans to finance their Yale education, loans are never the only choice. But Blackmon said this is a “warped way of thinking” and that “no one chooses to take out loans.”

Lozano said she sees Yale’s portrayal of its financial aid policies to prospective students to be “so dishonest.”

“Yale, you [promised] to give loan-free need-based financial aid, and that’s just not what happened,” she said.

Eight of 10 students interviewed echoed the sentiment that Yale’s financial aid policy is misleading. Specifically, they mentioned that in the profusion of information about various kinds of financial aid, they did not understand the scope of student effort until arriving at Yale. One student even mistook it for a one-time entrance fee. The few that were aware of it before receiving their first bill noted that they envisioned it to be more feasible.

Julia Hamer-Light ’18 said that while she knew about the student effort, she assumed it was easily achievable before coming to campus.

“When I came to Yale, I thought Yale would have a system or structure in place that would allow students to [pay it] in a way that makes sense. I have not encountered any of that” she said.

Students also noted that high school counselors and admissions brochures depicted a Yale education as 100 percent free for low-income individuals. Some scholarship programs pledge full financial aid for four years, but they do not always cover the student effort. The Questbridge Scholarship, for example, functions the same as a Yale financial aid award and does not cover the student effort portion.

All students emphasized that they always planned to work while at Yale to earn money for miscellaneous expenses and in some cases to be financially independent from their families. However, they did not envision needing to use money from work to pay for the student effort.

The desire for financial independence is especially poignant for students whose families cannot provide money for the incidental expenses of life at college. Espinoza, whose mother works at a food processing plant and whose father is unemployed, sought such independence through a student job. He applied for around 25 jobs when he first arrived on campus.

“What originally was for me to be financially independent became me working to pay Yale,” he said.

Summertime, When the Livin’s Not Easy

The summer after his sophomore year, Marc-André Alexandre ’17 found himself painting walls in his old high school in Montreal. A six-hour car ride away, in New York City, many of his classmates were interning at nonprofits, conducting research or trying their hand at finance. The thought never crossed his mind.

Alexandre, a member of the varsity track and field team, spent a portion of the summer training and participating in track meets. As a result, he did not have three months to spend at a paid internship. He returned home in order to make as much money as he could to pay the SIC, and his parents helped contribute the rest.

While the self-help portion of the student effort is meant to be met through term-time work, the SIC is intended to derive from student work over the summer. Currently, the student income contribution is $1,625 for freshmen and $3,050 for all other class years. Students interviewed criticized the expectation that they earn money over the summer, saying that it contributed to divergent Yale experiences.

Students who must meet the SIC, and who do not have the help of parents, loans or outside scholarships, often cannot consider unpaid summer internships. This is particularly problematic for freshmen and sophomores, grade levels that typically engage in this type of summer work.

Hamer-Light said her summer search came down to three factors: job quality, capacity to cover living expenses and ability to pay her $3,000 SIC. An unpaid internship was not in the realm of possibility, Hamer-Light said. She ended up interning at Artspace, a local New Haven nonprofit, through the President’s Public Service Fellowship, which pays its fellows a sizable stipend.

She noted that although she was living frugally in New Haven, she barely made enough money to cover the contribution, despite the fellowship being listed as a summer job.

“The main issue for me is summer contribution, because that is a very clear barrier to having experiences that will help you with your career later,” she said. “How we build our careers is by making connections during the summer months.”

In his first two summers, Blackmon interned for nonprofit advocacy groups, for which he received a small stipend. To pay for his student income contribution he took out loans, noting he did not want to sacrifice his summers for the SIC.

He said that as low-income students come to Yale already disadvantaged compared to their wealthier peers, any sort of leveling process that occurs during the year evaporates over the summer.

Working for a Change

In his first ever freshman address, University President Peter Salovey spoke of socioeconomic mobility as a central pillar of the university’s mission since its earliest days.

He cited the famous Yale historian George W. Pierson, a man known as “Father Yale,” who wrote, “half the boys in each colonial class were from families of no social standing. In the 19th century Yale continued to attract and to care for many of the most modest means.”

For many students, Yale seems to have lost sight of its goal to stay affordable for low-income students, and within the last few years, student activism has returned to campus in a variety of forms.

After financial aid reform became an important issue in the 2014 Yale College Council presidential election, the YCC formed a task force to identify areas of possible improvement. The report contained a set of findings and a series of recommendations for administrators, and relied largely on a comprehensive financial aid survey sent to the student body.

According to Blackmon, who chaired the task force, the report provided a platform for students to meet with administrators. YCC members had approximately five meetings with Quinlan, Storlazzi and Provost Benjamin Polak, but Blackmon said they were largely frustrating, as the administrators, in his opinion, were reluctant to speak about actual policies or numbers. Instead, they preferred to speak about issues of communication, such as improving the financial aid website. He also pointed to a disconnect between students and administrators.

“I used to think the administration recognized there was a problem but couldn’t do much about it. It turns out that’s not the case at all,” he said. “What I realized in those meetings is that they just don’t think it’s a problem. They could do something if they wanted to.”

In an email to the News, Quinlan said he and Storlazzi are aware that no system or set of policies could address completely every student’s individual or family situation. He added that “the data we review tell us that we are doing well in meeting the commitment to make Yale affordable for all students.”

This year, the executive board of the YCC, Quinlan and Storlazzi established a working group to discuss issues surrounding financial aid. Made of up four students and some administrators, the group works to connect concerns of students with the administration. It has met twice this semester and will meet again next Friday.

According to JT Flowers ’17, a member of the working group, the purpose of the group is to provide a comprehensive analysis of financial aid policy with both student and administrators sitting at one table. He added that he has found Quinlan and Storlazzi to be “surprisingly receptive.”

In addition to student-administration conversations, activism amongst student groups has increased. Flowers founded an organization, A Leg Even, which works, according to its website, to combat the challenges inherent in the college experiences of Pell Grant recipients — students designated by the U.S. government as requiring the highest amount of financial aid.

The group Students Unite Now, one of whose goals is making Yale more accountable to its constituents, has been particularly active regarding this issue.

In late February the group organized a gathering of 100 students in front of Woodbridge Hall, calling for Yale to eliminate the student effort component of financial aid. It delivered a petition with over 1,100 student signatures calling for the elimination of the contribution to Storlazzi and other administrators, and has also held meetings with residential college masters and Storlazzi. “While Yale tells me constantly that higher education and intellectual pursuits are for me, its financial aid policies — from the application to the work requirement — tell me otherwise, with the jobs and concerns put on our plates on top of school and extracurriculars,” SUN member Jesús Gutiérrez ’16 said in an email. “I want academia to be mine, and I am invested in more students of color teaching and writing books, investing in brighter futures for our communities. How can we do that when the institution itself is responsible for one of our greater obstacles?”

An Uncertain Future

Nine hundred miles away, at the University of Chicago, the Odyssey Scholarships program works to increase aid and programming for low-income students through greater financial support, career guidance, personal mentorship and community support.

Created in 2008, the scholarships were formed to eliminate the need for student loans among low-income students. Last year the university enhanced the program further, and students now have no employment requirements for the academic year, freeing their time for academic and extracurricular development. They also are guaranteed paid summer internships or research opportunities after their first year, as well as career and leadership training, although the average University of Chicago student still receives a lower financial aid award than a Yale student.

For students at Yale, a comparable program does not exist. While all students interviewed preferred the abolition of the student effort contribution, many said they would be pleased with a reduction. They said a reduction in the student effort would allow them to experience the same Yale that their classmates do, in which jobs do not impede personal or intellectual development.

Those interviewed did not agree on prospects of change; two saw a complete elimination of the student effort as unlikely, while others viewed it as a possibility after their time at Yale.

“Often what drives Yale to act is Harvard,” Blackmon said. “We joked that to really change financial aid policy we need to get a train to Cambridge and lobby the Harvard administration.”

Lozano hopes financial aid reform will help those students who are forced to rely solely on work, not scholarships or family, to pay for their student effort. As a first-generation college student, she said she and her family were unprepared for the whirlwind of financial aid complications.

“Yale compared to other schools is helping me so much, and I am grateful for that,” she said. “But the reality is this is further increasing social inequality on campus, and they need to know that.”