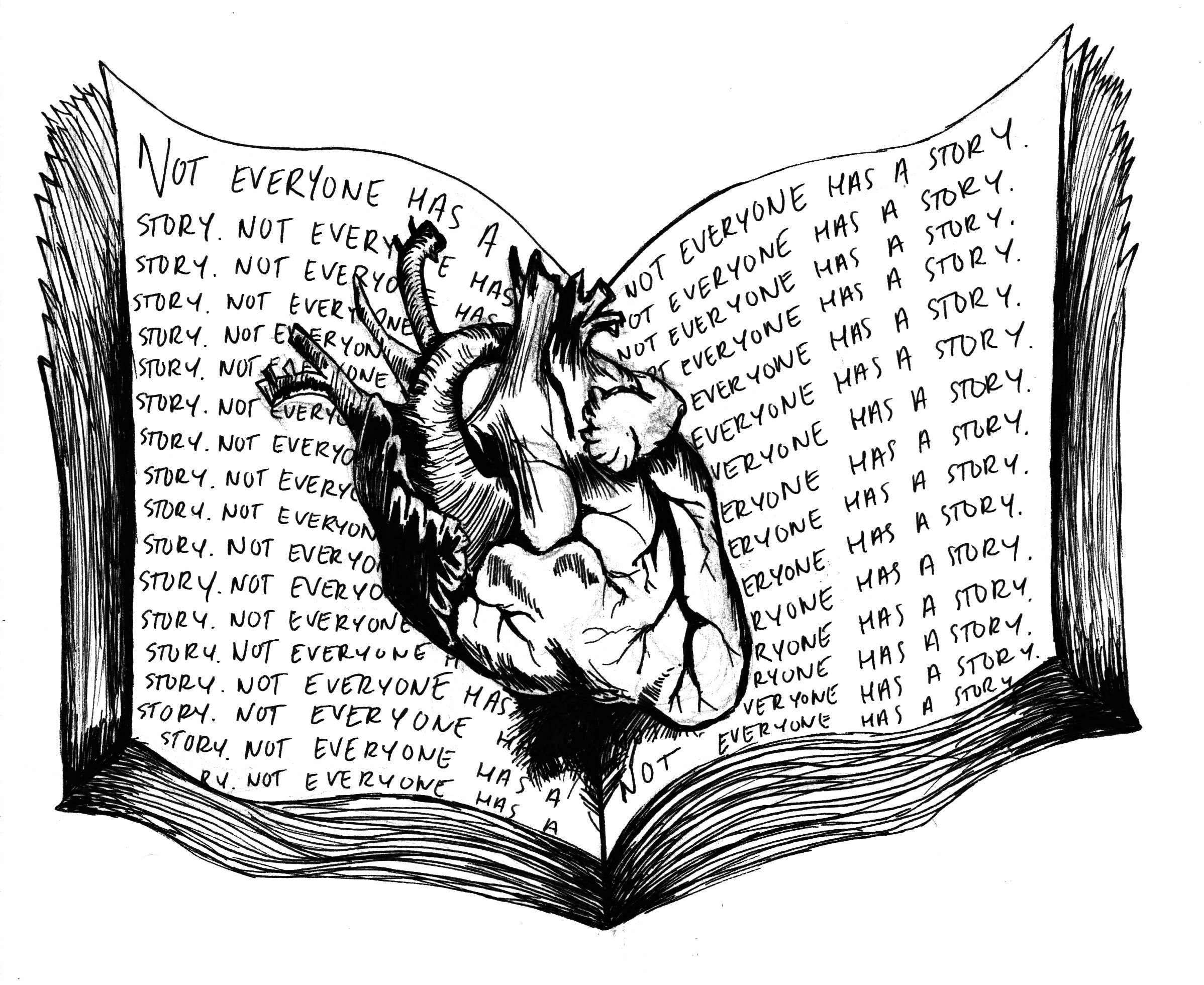

What’s your story?

We have all been confronted with this question in one form or another: through a college application essay, at an initiation event for an extracurricular or during a heart-to-heart with a suitemate. If you can’t quite find the words to tell your own story, that’s okay, too. Upload 24 hours’ worth of pictures and Snapchat will create one for you.

I have no doubt that some people genuinely think of their lives as narratives (of triumph, struggle or something in between). But I am just not one of them. And I suspect most people aren’t, either.

Of course, I have full knowledge of my biographical particulars. I know (or at least I think I know) where I was born, who my parents are and what schools I went to. What I dispute, though, is that these details constitute a coherent story with explanatory power. To conceive of our lives as stories is to impute them with a unity and linearity that do not exist.

For one, our “stories” would be very boring if they were to be published, since they all end the same way. No suspense there. I am not sure they would have easily discernible themes, either — my story would be more Virginia Woolf than Aesop’s Fables. Moreover, we would always be trying to close chapters in our life, only to find that the writing keeps spilling over. And just as we thought we had a good outline, we’d find ourselves with too many plot twists.

Plagiarism would pose a problem too. We like to think of ourselves as unique, but I know I probably have hundreds, if not thousands, of doppelgangers, with similar interests, personalities and experiences. In curating our lives, we often find ourselves professing a certainty in causality, when that certainty does not and should not exist. For instance, why do I get so worked up when people don’t reply to my text messages? Childhood experiences of rejection? Genes? Or are these just after-the-fact explanations for parts of myself I don’t like?

If our life stories were fictitious, but served practical functions, they might still be worth crafting. Unfortunately, the idea that life is a story is damaging for a number of reasons. Whenever I think chronologically about my life, I end up having an existential panic attack. How does the time I waste watching YouTube videos fit into my “grand narrative?” Where will losing my sock while doing the laundry on Tuesday feature in my autobiography?

Type A personalities might argue that this preemptive “writer’s block” helps me focus on what truly matters. But maybe there should be room for meaningless moments where the mind can simply wander, or for the idiosyncratic routines that serve no apparent purpose. And perhaps the best moments in our lives are fleeting and spontaneous — climaxes without rising actions or denouements.

There are also ethical risks for the narrativists to consider. If I see myself as the protagonist in my Life Story, it becomes all too easy to cast anyone who obstructs my happy ending as the evil stepmother. We can become too glib and too slick in telling and re-telling our origin myths, until we use them to justify our shortcomings and mistakes. A story creates the illusion of inevitability, removing personal agency and thus absolving us of guilt. In the process, stories become the dominant mode of moral reasoning, replacing principles and virtues.

Whenever I tried to tell my freshman suitemate about my day, he would tell me that my stories had no plot. That taunt no longer bothers me. Organizing my life into neat, readable volumes simply takes too much effort. Time after time, my reality is but a parody of the fantasy I invent. Far better, I think, to ditch the narrative genre, and treat every moment as its own beginning. Make an impact on something, rather than making fragile meaning out of nothing. In the end, no one really cares about the story of your life except you, who won’t be around to read it when the tour de force is complete. A self-published novel you spend your whole life writing goes unread: that would be the real tragedy.