“The Winter’s Tale” was written by the Bard of Avon — the man colloquially known as Shakespeare — in the 16th century. And in true Shakespearean fashion, the play’s events are centered on the paranoid King Leontes, played by Iason Togias ’16. In the opening scene, Leontes asks his wife to charm his childhood friend, King Polixenes, into staying in his kingdom a little longer. But when his wife lays on the smiles and the laughter, Leontes becomes obsessed with the notion that his best friend and his wife are sleeping together. The king naturally reasons that his son isn’t his son, and that his pregnant wife’s child isn’t of his blood either.

The Yale Dramat removes the familiar play from its 1580s context. Rather than setting the play in Shakespeare’s simpler time — when only women whom men denounced as hysterical raved — the Dramat’s production features teenagers wearing clashing prints and goofy grins in strobe-lit raves.

Director Katie Kirk ’17 seeks to highlight the combating forces of the kings and their traditions somewhat obviously by transporting the characters to approximately 350 years after Shakespeare’s time: namely, the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall. The resulting reunification of Germany is intended to echo the rekindling of Leontes and Polixenes’ friendship after one accuses the other of having sex with his wife.

Transporting the plot to a radically different time in order to accentuate the play’s core themes of forgiveness and transformation was an ambitious move, but it fell flat most of the time. The cultures of the two sides of Germany — East and West — were incorporated into the characters, but only on a superficial level. The characters weren’t different for having lived in West or East Berlin; they were just dressed differently. Berlin didn’t add another level to the play. It was just colorful scenery.

Though the setting and set design highlighted the play’s core themes minimally, the show didn’t need too much help in the first place. This production’s strength lay in its actors.

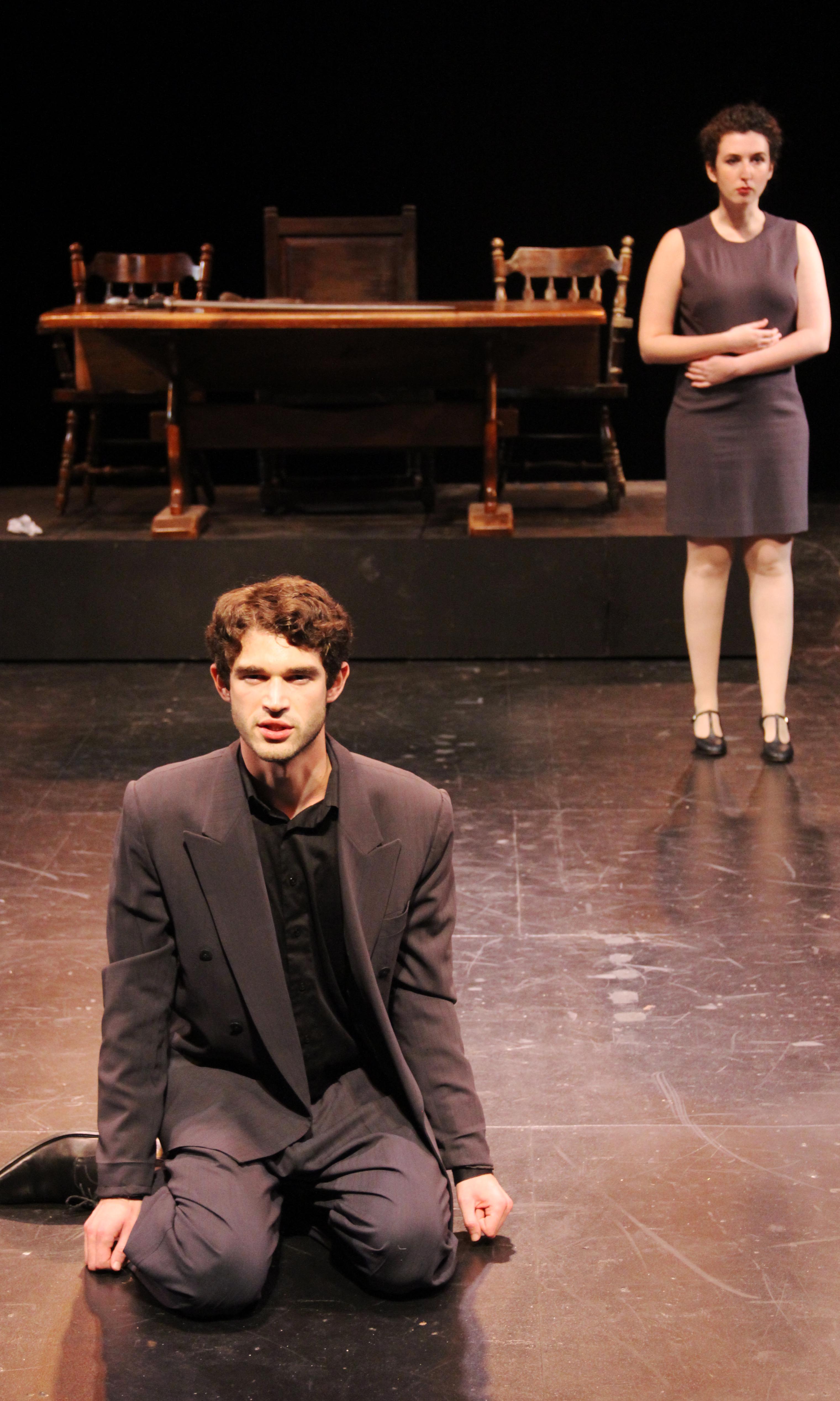

Iason Togias ’16 was perfectly adequate as Leontes, the paranoid king who accuses his good friend Polixenes — played by Dillon Miller ’18 — of infidelity with his wife. Togias conveyed happy and angry and sad, but only sparingly did his emotions register levels that the audience could feel. Leontes, the mad king, was just that: an archetype.

There was a scene, however, in which Togias elicited goose bumps. Leontes had just learned of his family’s deaths, a direct result of his unfounded paranoia. Togias’ face was numb and his hands limp. He crumbled onto the ground in a powerful emotional scene.

Alec Mukamal ’18 played minimal parts for comic relief. The character he shines as doesn’t even have a name — he’s just the Shepherd’s Son. Mukamal’s hilarious overacting was a much-needed break from the quiet intensity of many of the other actors.

In one of the last scenes of the show, soft and soulful elevator music plays in the background as Leontes is reunited with most of his family and his friends. Leontes hugs Polixenes … Leontes’ daughter hugs the Shepherd … Polixenes’ son hugs Leontes’ daughter … The five-minute scene of the characters’ reunification is supposed to leave us teary: this is the happy ending that the audience was waiting for. Instead, the sappy music and the ’80s outfits make it almost comical, an example of how “The Winter’s Tale” could have either handled the culture differences between Leontes and Polixenes or between West and East Berlin. But it tried to do too much, diluting the intended effect.

Though the actors were all capable in their own right, the casting directors of the play apparently found that transporting the play more than 300 years in the future would be easier than reimagining it with people of color. The cast is all white, or at least all white-passing.

The Winter’s Tale is ambitious — more so than a typical modern revival of a Shakespearean play — but overall, it falls flat trying to do so much. The show juggled themes of betrayal, the strength of familial ties, friendship and the needs of loved ones — and the backdrop of the Berlin Wall didn’t render them more clear or powerful. It lessened their impact.