Conservationists, tropical foresters gather for ISTF conference

The 31st Annual Conference of the Yale Chapter of the International Society of Tropical Foresters brought together global leaders, climate scientists and indigenous activists.

Michelle So, Contributing Photographer

The School of the Environment’s Kroon Hall took on a lively atmosphere as innovators, entrepreneurs and advocates arrived early Friday morning.

The 31st Annual Conference of the Yale Chapter of the International Society of Tropical Foresters took place on Jan. 31 and Feb. 1, with over 300 in-person participants and hundreds more on Zoom. Themed “Governing Resilient Tropical Forest Systems,” this conference emphasized integrative conservation approaches.

“We [face] many different challenges, and one has to do with the fact that more and more human[s] are losing contact with nature,” Carlos Manuel Rodriguez, the CEO and chairperson of the Global Environmental Facility, said. “The new generations, these kids never milk a cow, they never ride a horse, never walk in a protected area. They’re not exposed to natural ecosystems. They don’t know where the freshwater is coming from.”

Rodriguez was the first keynote speaker at the event. His presentation touched on environmental conservation efforts in Costa Rica, where he served as the Minister of the Environment for three terms.

As a child, Rodriguez dreamed of becoming a tropical biologist who “worked with jaguars and tapirs.” While he never became a biologist, he remained a staunch advocate of the environment, following in his father’s footsteps and attending law school to become an environmental lawyer.

“Even though I don’t do research and I never worked in any specific protected areas, I became a decision maker who was able to develop institutions, policies, incentives, programs and actions that protect the nature,” Rodriguez told the News.

Rodriguez’s take on environmentalism was echoed by International Society of Tropical Foresters Conference Co-Chair Ananya Rao ENV ’25, who thinks forestry has “evolved into a much more expansive space.”

Rao, originally from Bangalore, India, said that the School of Environment created a space “for all of these different aspects of forestry people coming from finance, from social sciences, from the humanities all being allowed into the space.”

Rao, along with Co-Chair Felipe Storch de Oliveiria ENV ’25, has been planning the event since April 2024.

Rao was most excited about panel two, “Ground Up Forest Governance in a Changing Climate: Perspectives from Indigenous and Local Communities.” Speakers included José Domingo, a Mam Mayan Indigenous leader from Guatemala, and Bola Madzoke, an ecologist from the Lac Télé Community Reserve.

“We’re having people who are not normally seen in spaces such as these, especially because of language barriers,” Rao told the News before the conference. “It’s going to be a multilingual panel with a lot of different languages flying around and a lot of really valuable perspectives that we don’t normally get to hear.”

Dylan Rose ENV ’26, who led fundraising and budgeting, was particularly inspired by Rodriguez.

Rose, an amateur photographer with a “decent-sized portfolio of tropical biodiversity and landscape photos,” had his work displayed on TV screens around Kroon Hall.

“I took a few field courses in Latin America during undergrad, mainly in Costa Rica and Panama, but I always kept my camera on hand,” Rose said.

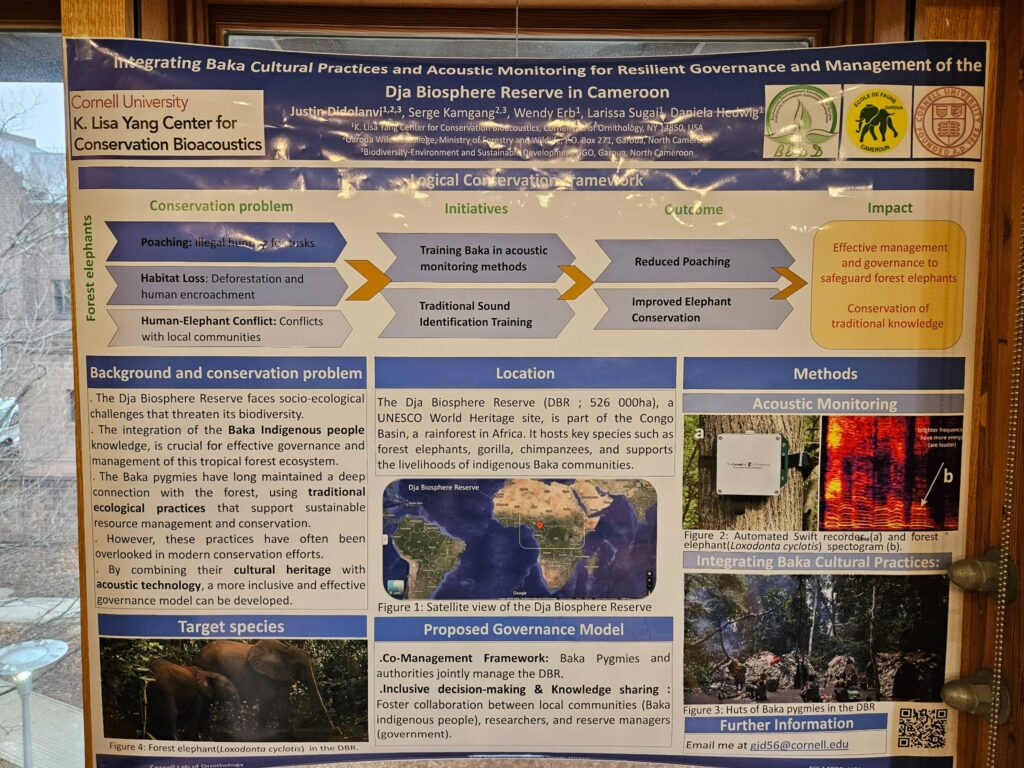

Originally from Cameroon, Justin Didolanvi, a current student at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, presented his research on using acoustics to study forest elephants in the Dja Biodiversity Reserve in southern Cameroon.

According to Didolanvi, elephants are important keystone species of the tropical rainforest and often trample into village areas. When they do, human-elephant conflicts can arise, putting both in harm’s way.

Didolanvi worked with a local Indigenous group, the Baka Pygmies, that “knows everything about the forest.”

“The idea here is to try to see how we can involve the local communities that have a very long-term connection with the forest. They spend all their life in the forest, so they know everything about the forest,” Didolanvi said.

In the past, government officials and police have tried to get the Baka people off their land, deeming them unsafe for civilization, according to Didolanvi.

This project not only provides Didolanvi’s team with crucial data but empowers the Baka people, he said.

Connection was a common theme amongst conference attendees. During the opening remarks, the International Society of Tropical Foresters co-chairs emphasized that collaboration is crucial for action.

“If we lose that contact with nature, it will be very, very hard,” Rodriguez said. “Your future is compromised by what my generation has done to the planet. So what will be the future if the youth is not a force of change and innovation today?”Over 420 million hectares of forest were lost from 1990 to 2020; 90 percent of loss came from tropical regions.