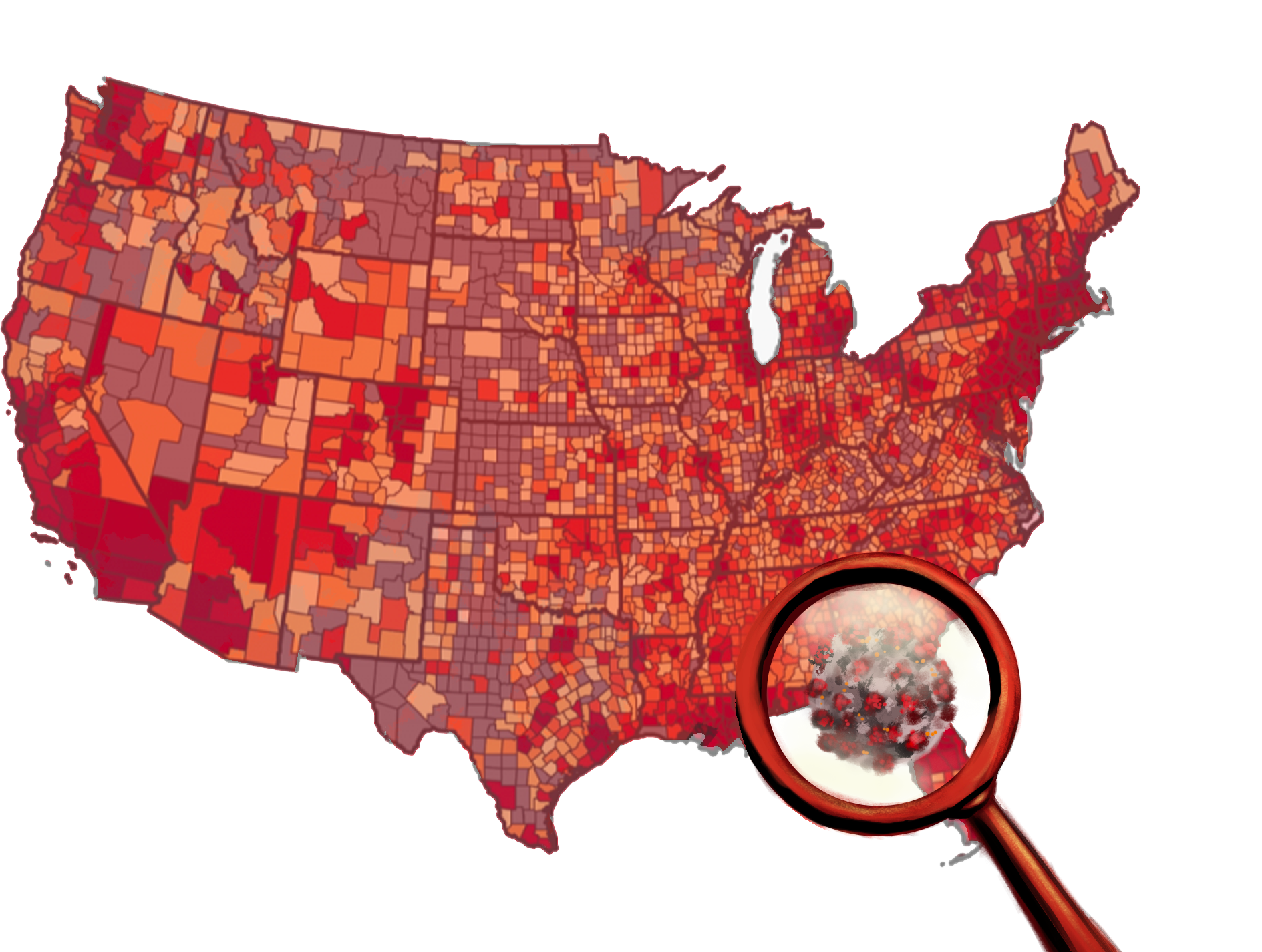

Kelly Zhou, Contributing Illustrator

Faculty at the Yale School of Public Health developed a new statistical model to track the spread of COVID-19 in the United States.

Researchers at the Yale School of Public Health and the T. H. Chan Harvard School of Public Health created a new tool, called covidestim, to track current COVID-19 cases on a state-by-state and county-by-county basis. The technology takes into account the latest information on the number of reported cases, death counts and disease severity to provide accurate information about the pandemic to citizens. Access to the online model is free to the general public.

“There is an urgent need for individuals to be able to access locally-relevant information so that they can make rational choices about how best to protect themselves,” professor of epidemiology Ted Cohen wrote in an email to the News. “Our model currently focuses on producing ‘nowcasts’ rather than forecasts of future epidemic behavior to allow individuals and policy makers to more accurately gauge current risk and understand the current trajectory of the epidemic.”

Cohen said that what distinguishes the covidestim tool from other similar COVID-19 tracking technologies is the way the model combats delays in data reports of symptomatic COVID-19 cases and deaths. He noted that these lagtimes have traditionally created an incomplete picture of the pandemic’s spread.

He explained that covidestim draws on information about the natural history of infections and accounts for these delays in order to produce the most accurate, plausible range for the number of infections at the current moment.

“Our model is really concerned with correcting for gaps and delays in case and death reporting,” Melanie Chitwood, a research associate in the Cohen Lab and one of the project leads, wrote in an email to the News. “Our goal is to estimate daily new infections and the effective reproduction number; these quantities tell us about the trajectory of local epidemics.”

Accurately estimating an effective reproductive number — the average number of individuals that one infected person is expected to infect — is very challenging but crucial to measuring the growth of an epidemic, according to Chitwood. The model seeks to avoid biases and achieve “tighter estimates” by focusing on the number of daily new infections and combining that data with statistics that consider testing capacity and mortality risks, according to the covidestim website.

“Covidestim adjusts for these biases to provide an estimate of the current state of the epidemic at the local level,” said postdoctoral associate Joshua Havumaki, who contributed to the project. “The majority of other models for COVID-19 have been designed for other purposes such as predicting future case counts or estimating the effectiveness of interventions.”

Chitwood also highlighted the real-world utility of their new model. She explained that using covidestim has already profoundly aided her close friends and herself in gauging COVID-19-related risks.

She explained that a friend recently called her to see if it would be safe to visit family outside of Connecticut. When Chitwood and her friend examined the covidestim data set, the two realized that there were five times more infections per 100,000 residents in the county her friend was to visit. As a result, her friend seriously reconsidered making the trip.

“Understanding that the risk of illness is different across counties and over time is really important right now,” Chitwood said. “Things may feel safe in New Haven, but we do see that daily new infections are increasing. Things that were relatively low risk last month might not be next month. It’s important that we stay vigilant, even if it feels safe here and now.”

According to Cohen, researchers are continuing to develop and improve the model. He mentioned that the team is currently working to modify how the model estimates seroprevalence — the number of people in a population who test positive for a specific disease based on data from serum samples, such as blood.

Cohen also hopes that the model will eventually take on a predictive capacity, enabling it to forecast future trends in the disease’s spread.

“In the future, we aim to build on this work to provide short term (1-4 week) forecasts of the epidemic,” Cohen wrote.

According to the covidestim model, the current rate of infection in Connecticut is 38 infections per 100,000 residents.

Sydney Gray | sydney.gray@yale.edu

Correction, Oct. 21: A previous version of the article misspelled Joshua Havumaki’s last name.