Shakespeare authorship doubts come home to New Haven

A conference of doubters has descended on New Haven to share theories about Shakespeare’s authorship rooted in the work of a 19th-century New Havener.

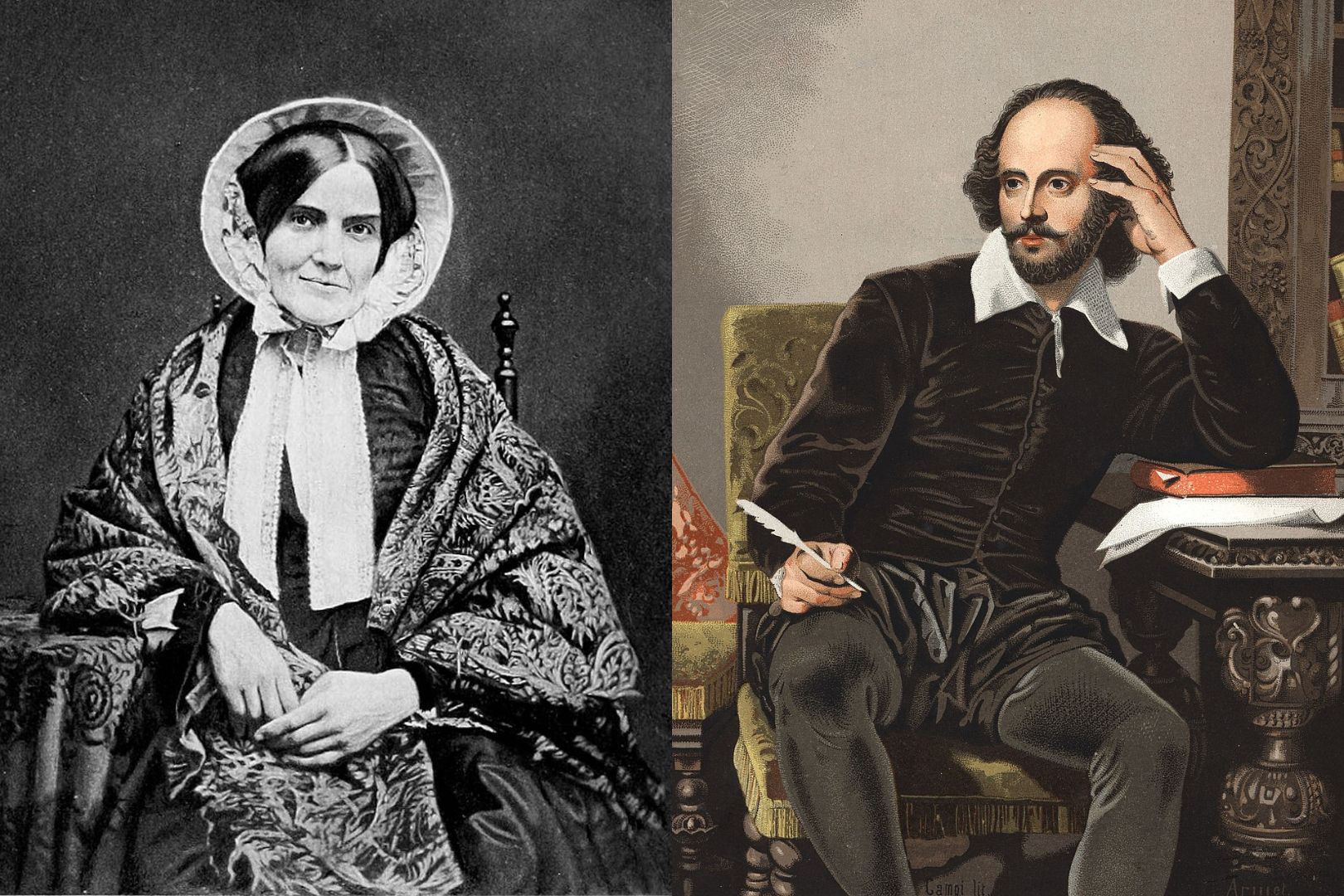

Wikimedia Commons

In 1840s New Haven, a young woman named Delia Bacon thought she had discovered the truth about the author we all know as William Shakespeare. Shakespeare, Bacon claimed, had not really written his plays.

On Thursday afternoon, over 50 of Bacon’s disciples gathered at the Omni New Haven Hotel to hear presentations at a conference regarding the so-called “Shakespearean authorship question.”

The conference was organized by a society, the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, that promotes the widely discredited theory that Shakespeare was really Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. From a podium set between two projection screens, speakers explored the lives of Elizabethan aristocrats and suggested ciphers that could be used to discover hidden code in Shakespeare’s sonnets.

The organization’s theory — called the Oxfordian theory — is that de Vere, a prominent figure in Elizabethan England, published under a false identity, which he borrowed from a semi-literate William Shakespeare.

“There was no theater in the whole history of the family,” conference chair and York University professor emeritus of theater Don Rubin said of Shakespeare’s family. “In fact, the family was illiterate, going back generations and forward. He never educated his daughters.”

Rubin, now a Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship lifetime member, told the News that he attended his first Fellowship conference in Houston “for a laugh,” only to be “knocked out by the seriousness of what they were saying.”

The Oxfordian theory, Rubin said, is “truth,” and the widely accepted academic consensus — the Stratfordian theory — is “myth.”

“You got all these people in Stratford, with the Stratford Birthplace Trust, who are living a myth,” he said, referring to an organization responsible for Shakespeare heritage sites in Stratford-upon-Avon. “And they prefer the myth to the truth.”

Brent Evans, the president of the Fellowship, called the Stratfordian theory an “embedded truth.”

He recalled telling a friend that he was questioning whether Shakespeare had written the plays. “Is nothing sacred? Are we questioning everything?” Evans recalled his friend asking. “Shakespeare has godlike status among the literati, and you don’t touch it,” Evans added.

The Oxfordians argue that the academic consensus on Shakespeare’s identity is the result of an unhealthy obsession with the mythology of Shakespeare.

Yale English professor Catherine Nicholson, who is teaching a Shakespeare lecture course this semester, does not find this argument credible.

“My objection to, say, the Oxfordian theory of authorship is not at all that it attacks a kind of figure, a narrative to which I’m attached,” Nicholson said. “My objection to it is that it is unproven and also designed in some ways to be unfalsifiable.”

Authorship doubts may in fact be the product of Shakespeare’s mythification, Nicholson said.

“The kind of perennial excitement that attaches to the possibility that in fact we’ve been misled — I think that excitement only makes sense if you have an attachment, a kind of powerful attachment,” she said.

Part of Nicholson’s interest in Shakespearean authorship theories comes from how they relate to “the question of the boundaries of institutional knowledge, the boundaries of scholarly discourse, the place of disputed or refuted theories,” she said.

These questions characterize the current historical moment, Nicholson argued. “Immunology, vaccines, anything you can think of. Physics, string theory.”

“It’s interesting,” she said, “to think about the world of Shakespeare studies as having been sort of ahead of the curve in this respect, in that Shakespeare studies has long had this kind of marginal, discredited, but also extraordinarily persistent and compelling group of people.”

Thursday’s keynote paper, written by Evans, is titled “Was Delia Mad?” It chronicles Bacon’s life, her theories, her institutionalization and her ultimate death at the Hartford Institute for the Insane. Conference attendees gasped and murmured audibly when Evans described treatments, including straitjackets and frequent sedation, which he claimed were commonplace at the institute.

Evans concluded his presentation on a positive note.

“We are standing on her shoulders,” he said. “We can now see her life and legacy as a triumph.”

Not all conference attendees had prior knowledge of Bacon, but after Evans’ presentation, admiration for her seemed ubiquitous.

Annette Vise, a first-time conference attendee who said that she began to question Shakespeare’s authorship while in eighth grade, called Bacon “a woman ahead of her time.”

“We discover things that we had no clue about,” Lucinda Foulke, a retired editor of the Fellowship’s newsletter, said. “I didn’t know that Delia Bacon had really done this kind of research in the 1850s.”

Although not persuaded by Bacon’s “imagined conspiracy,” Nicholson told the News that she “would not want our alternatives to be ‘Delia Bacon was right about Shakespeare’ or ‘Delia Bacon was a madwoman.’

“I would like us to be able to take Delia Bacon seriously as a figure who is important and interesting, has had — has unquestionably had — an effect on the world of Shakespeare studies,” Nicholson said.

On Sunday, the final day of the conference, Evans is set to lead a group to Grove Street Cemetery to visit Bacon’s grave.

Interested in getting more news about New Haven? Join our newsletter!