It’s an old saying that you should never meet your heroes. The validity of such a statement, I cannot affirm — I never got the chance. In the sixteen years that Joan Didion and I prowled the same crosswalks of New York City, I was entirely unaware of her existence. It was only the summer following her passing that I first picked up “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and, in the two-and-a-half years since, have scarfed down every book that has her name printed on the cover.

To think that I might have unknowingly crossed paths with Didion during those sixteen years, her presence registering with me as nothing more than a woman sporting thick-brimmed sunglasses, a woman scarcely surpassing my barely five-feet-tall mother in stature, is, to me now, astounding.

Yet despite our time spent in the same city, any true Didion devotee knows her soul resides in California. So when it came time to visit my cousins in Los Angeles over winter break, I realized this was my chance to seek out California as Didion knew it. If I couldn’t directly observe the person I strive to be, the least I could do was orient myself through her map.

In preparation for my trip, I looked back at some of Didion’s pieces on Los Angeles. I was struck, in particular, by a section of “The White Album” where she describes the West Hollywood house that she rented for five years in the late ’60s. According to Didion, while the structure of the house itself was spacious and high-ceilinged, its facade was near disintegration. The home’s exterior had “paint peeled inside and out … pipes broke and window sashes crumbled.” But what followed such a picture of the home’s rawness was a spiritual description of how it transcended its physicality. She wrote, “during the five years I lived there, even the rather sinistral inertia of the neighborhood tended to suggest that I live in the house indefinitely.” I decided I needed to make a pilgrimage to view the home on Franklin Avenue myself: what better place could there be to visit for a person who quasi-jokingly refers to Didion as ‘Saint Joan’ on the daily?

Upon arriving in Los Angeles, I realized that my cousin’s house was within walking distance from the home. A quick Google search told me that it was now run by the Shumei America Hollywood Center, a spiritual organization that describes itself as “dedicated to advancing health, happiness, and harmony for all humankind through applying the insights of its founder, Mokichi Okada.” I found the notion of a community guided by the principles of “natural agriculture,” nestled in the heart of West Hollywood and in the home that Didion claimed to have a near-supernatural bond with, irresistibly intriguing.

I immediately concluded that the group must be a cult, and I crossed my fingers, hoping it was indeed one. This was the kind of investigative journalism that Didion herself would have pursued: she would have written about a nature cult in the middle of Hollywood Hills.

On my first day in Los Angeles, I sprang out of bed at 6:30 a.m. I shuffled into the bathroom, showered and threw together an ensemble that vaguely adhered to the Joan Didion playbook for the quintessential reporter: a cotton shirt paired with a cardigan hung over my shoulders and my favorite pair of jeans — although Didion seemed to exclusively wear skirts when reporting, I went off the dress code for the sake of my own comfort.

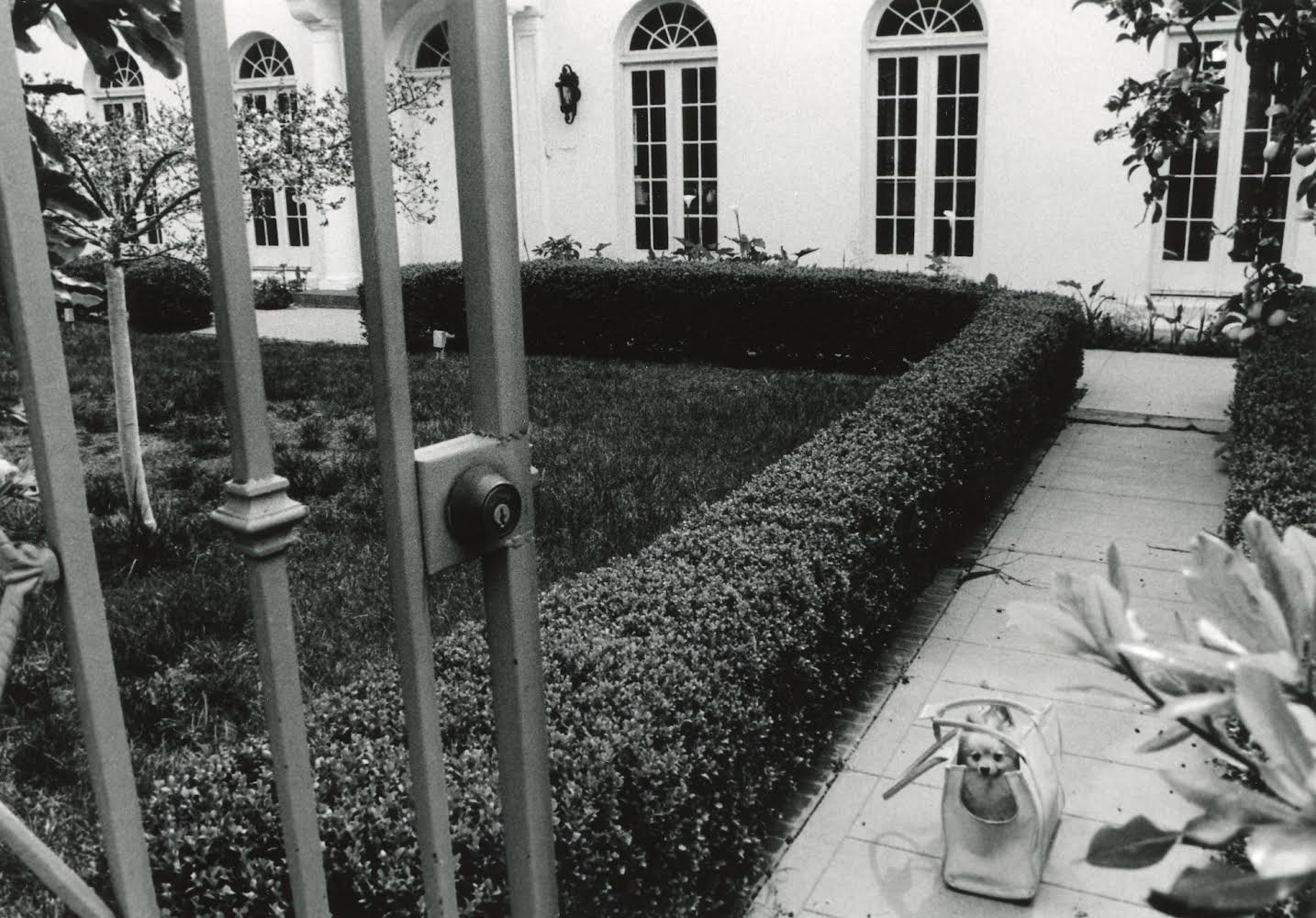

I grabbed Luna, my cousin’s pomeranian who spends more time in a bag than on foot. I’d promised to dog-sit and figured if things went south with the nature cult, they might take pity on the girl with the dog.

As I walked towards the home, I drifted into a meditation on how Didion might perceive this assignment: would she too feel herself, point blank freaking out? Or, in characteristic composure, would she regard this quest as child’s play?

All of these thoughts ceased once I found myself a block away. Palm trees, towering at least fifty feet in height, adorned both sides of the thoroughfare, their fronds seemingly intermingling in the wind. On one side of the street, the side where 7406 was located, homes emerged like siblings, pristine in their wedding-cake white, epitomizing the traditional allure of Hollywood. The homes on the other side of the street were of a greater variety: hues of tan and red, interspersed with the occasional apartment complex. As I approached 7406, I couldn’t shake the echo of Didion’s reflection on her arrival in New York at the age of twenty. “Was anyone ever so young?” she had written — a musing that resonated with me as a firm statement rather than a question. Here I was, with half-dried hair and a dog in hand, standing in front of the home of my late idol. Was anyone ever so young.

A seafoam-colored gate enclosed the home, ornamented with three separate rustic signs bearing the number 7406 pyrographed atop of them. Green leaves and plants sprouted from behind the gate, spilling over its boundaries. Weakling lemon trees bearing neon-hued fruit peeked out tantalizingly. On the opposite side of the home, smaller and sturdier cherry trees flourished, their delicate blossoms tinted a vibrant shade of light pink.

The house itself strayed far from Didion’s 1960 description. Back when Didion lived in the home, her acquaintances described this part of Hollywood as a “senseless killing neighborhood.” In the years since, it has turned into one of the most affluent neighborhoods in the world. The house stood starkly white, almost aggressively so, with a brilliance that made one wonder how a color that vivid could possibly be maintained.

I stared out into the garden, which had once been roamed by the likes of Janis Joplin and Patti Smith at Didion’s fabled dinner parties. I could imagine Didion herself roaming this garden frequently, struck many times on this soil by strokes of genius — thoughts so irresistible they make you drop everything to go get a pen and paper. Her introspections and reflections that I held in such high regard could have come to her here. Possibly on the very stoop that I sat on.

I sat there for about an hour, hoping to absorb some of Didion’s spirit. Instead, my notebook read: “I am not allergic to lemon but the smell is so strong I might be soon enough” and “I can only liken this experience to a religious one.” On the porch of a master writer, the best I could come up with were notes about my clogged sinuses and parasocial relationship with a dead woman. Was anyone ever so young.

I eventually quit attempting to write and decided to wander to the back of the house. I entered the vastest, most lush garden I had ever seen. Large stocks of green plants sprung up from the ground with cartoonesque flowers spurting out of them.

Several signs around the garden with the embossed words “Welcome To The Shumei Hollywood Garden” caught my attention. This was the first indication I had of the home actually being run by this nature spiritual organization. Each sign was split up into three sections: “Our Philosophy,” “History of the Garden” and “Frequently Asked Questions.”

Underneath the “Our Philosophy” section was written:

“The practice of Natural Agriculture is based on a highly developed philosophy that integrates art, beauty and nature into all aspects of life. It is intimately tied to the physical and spiritual laws that govern the universe, as perceived by its founder. The unique contribution of Natural Agriculture is its fundamental respect for all elements involved in the natural growing process — light, soil, water and air. Natural Agriculture fosters a deep awareness of the contribution of each element and the benefits derived from working in harmony with them.”

I had never read a paragraph that said so little in so many words. What I found so jarring wasn’t necessarily the belief system itself, but the way it was communicated. This had once been the home of a woman defined by her masterful use of language, a home that this woman said she would live in “indefinitely.” And here I was, standing in that same space, reading language that felt vague and meandering. It wasn’t about judgement so much as dissonance: a kind of tonal whiplash between precision and opacity.

The “History of the Garden” section below only deepened my unease:

“The Hollywood Natural Agriculture Garden holds special significance as the first place in the western world to practice this way of farming. Farm Manager Junzo Uyeno first began working on transforming the half-acre plot of land in the backyard of the Shumei Hollywood Center in 1993. The area held an abandoned tennis court and a dilapidated flagstone barbeque area, both almost lost in a wild tangle of underbush, overgrown trees, and grass. It took Mr. Uyeno close to five years to clear the land and transform the hard rock ground into soil suitable for practicing Natural Agriculture.”

What was described seemed to mirror Didion’s description of her home in The White Album. Looking out into the most manicured garden I had ever seen, I found myself desperately wishing to see the overgrown weeds, trashed tennis court, and destroyed barbeque area that both Didion and the sign described. This home had a life, a history that had been stripped away in this man’s pursuit of “Natural Agriculture.” Why couldn’t he have picked another home? Why did he have to pick the home where Didion derived her inspiration, where she took solace and sanctuary? What gave this organization the right to deem her home ‘unkempt’ and completely renovate it?

If Joan believed she would live in this home indefinitely, and now that home has been destroyed, where does that leave Joan?

Two months later, I sat in calculus class, my attention focused on what was my newest senior spring fixation of the week: Zillow house stalking. I decided to look up my old home, apartment 2b, where I lived for the first decade of my life.

When I lived in it, the apartment was full of character: each room was painted in different neon colors, with craft projects, books and toys lining the walls. The home was as vibrant physically as it had felt to me in its essence. My memories of that time were of constant play: every action I took felt like an adventure, and every experience I had felt like a fresh, new lesson.

The home that Zillow displayed in front of me was entirely white, light gray and dark gray. Both my brother’s and my own room appeared to have been converted into home offices.

I felt that same gutting feeling in my stomach that I had felt two months prior, reading the signs at Joan Didion’s home. This time, however, it was a first-hand feeling.

Why would they rip it apart?

An irrational thought, perhaps. People can do whatever they want to the home they inhabit. It’s one’s right to orient oneself on one’s own terms. But why did it have to be my room, my house, that this family stripped to its core? The room that I had inhabited during the most formative years of my life, where I developed a consciousness and learned how to interact with the world?

Sure, the home we had inhabited looked like something out of a “Looney Toons” episode, with half-ripped scratch-and-sniff stickers melting into the walls and faded small smiley faces drawn with Crayola markers on the bottoms of chairs. To the raw eye, the home might have looked like what 7406 Franklin Avenue did to Junzo Uyeno in 1993: desolate, disheveled, overworn. But that was ignoring why it looked that way: it mirrored the thoughts I had in it, the laughs that resounded from its walls, the bright-eyed children who wanted a hand at decorating the house to make it into their home.

If I became who I was in apartment 2b, and now that home has been destroyed, where does that leave me?

Even though I have not set foot in it in practically a decade, I still find great solace in thinking about apartment 2b. I seemed to feel the same nostalgia for 7406 Franklin Avenue, a home I never inhabited and spent two mere, uninvited hours at. Maybe it was because Didion developed such a concrete image of the home in my mind. Maybe it was because she felt as though a piece of her would live in that home forever, just as I felt about apartment 2b. But maybe those pieces of us no longer exist. Was anyone ever so young.