“Cutting off a lifeline”: Lamont axes free tablets, messaging in prisons

Gov. Ned Lamont proposed eliminating free tablets, texts and emails for Connecticut’s incarcerated population at his biennial budget address last Wednesday.

Zachary Suri, Contributing Photographer

In 2021, Gov. Ned Lamont signed off on legislation subsidizing all communication services in state prisons. Now, free tablets, texts and emails are on the chopping block.

Lamont announced his plans to eliminate free tablets and electronic messaging for incarcerated people, which will save the state an estimated $3.5 million, at last Wednesday’s budget proposal. Incarcerated people will still have access to free phone calls.

“It’s hard to believe that out of a $55 billion budget, that these $3.5 million — which is less than 0.1 percent of the budget — is going to be the make or break point,” criminal justice attorney Alex Taubes LAW ’15 said. “[Lamont is] cutting off a lifeline of communication between people who are incarcerated and their families and their communities.”

Taubes and Barbara Fair, a longtime opponent of solitary confinement in prisons, voiced their shock and dismay at the proposed funding cuts.

Taubes highlighted criminal justice reforms Lamont has carried out in recent years, including passing the Clean Slate law, which erases misdemeanors and low-level felonies from criminal records, and sentence modification legislation.

“It’s like we’ve been betrayed by one of our closest friends,” Taubes said.

New Havener Darrell Atkinson, who served 31 years in Garner Correctional Facility before his release in May 2023, paid for phone calls and electronic messaging while incarcerated. Atkinson relied on his family to cover these communication costs, as he earned just $1.25 each day as head baker in the Garner kitchen.

In 2019, a 15-minute phone call in a Connecticut prison cost between $3.50 and $4.50. A spokesperson for the state Department of Correction said the cost of electronic messaging will be determined by the vendor; the cost in other states varies between $0.05 and $0.50 per message, according to a study by the Prison Policy Initiative.

Fair also highlighted the sub-minimum wage salaries incarcerated people receive, which she believes justify state-subsidized tablets and electronic messages.

“How dare [the state] say they can save $3 million?” she asked. “You’re saving millions and millions just with the cheap labor that you have from [incarcerated] people.”

Fair and Taubes noted that incarcerated people often use texts and emails to alert family, criminal justice advocates and lawmakers to misconduct by fellow prisoners and correctional officers.

For example, during sub-freezing temperatures in January, one of Taubes’ incarcerated clients messaged him about the heating no longer working in the Hartford County Correctional prison cells. After Taubes posted about the incident on social media, the client was transferred to a different facility.

Taubes also emphasized that free electronic communication with family and friends helps people “stay sane” throughout their incarceration.

“It kept the lines of communication open with loved ones, baby mothers, friends, family,” Atkinson said, reflecting on the role electronic messages played for him when he was in prison. “When you’re behind bars, you feel a sense of being by yourself and nobody’s there with you.”

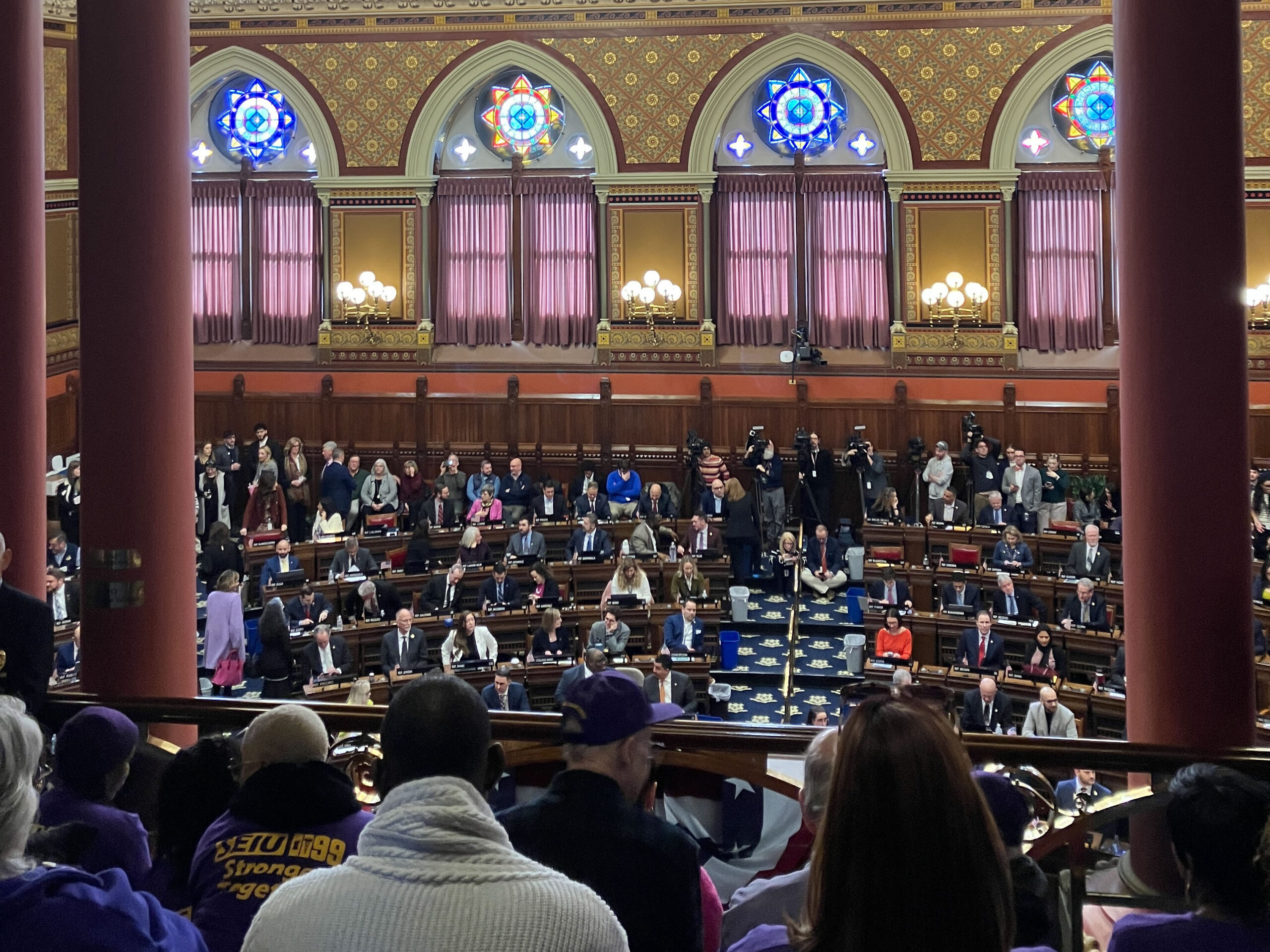

During a Tuesday public hearing about the public safety portion of Lamont’s budget, dozens of criminal justice advocates and formerly incarcerated people testified against the proposed elimination of free tablets and electronic messages.

At the hearing, DOC Commissioner Angel Quiros stated that these free electronic messages are “used 100 percent more than the phones.” He added that the subsidized messages likely reduced incarcerated people’s chances of recidivism.

Taubes expressed frustration about reinstating funding for tablets and electronic messaging potentially taking center stage in the current legislative session, which he said would prevent more radical criminal justice reforms from getting considered.

“If we’re fighting this session just to keep the free emails, we’re not going to be fighting to expand the access to public defenders,” Taubes said. “We’re not going to be fighting to get more compensation for the wrongfully convicted. We’re not going to be fighting for reducing the amount of people who are incarcerated. It’s a massive distraction from any forward movement on the agenda.”

Prisoners can send 10 electronic messages and receive up to 75 messages each day, according to Quiros.

Interested in getting more news about New Haven? Join our newsletter!