Is fashion political? Despite what some of us may think, every outfit is a coded declaration of how we wish to be presented. I’m reminded of the iconic “Cerulean” speech from “The Devil Wears Prada,” where Miranda Priestly, played by Meryl Streep DRA ’75, absolutely obliterates Andy Sachs for believing she’s exempt from fashion’s influence — only to prove that even her “frumpy” sweater is the product of industry decisions far beyond her control. Ouch.

For most students, we make these statements not through the purposeful selection of clothing — whose meaning is only revealed through an analytical eye — but through pieces of plastic that plaster our political and personal views with no room for interpretation. A bright red “Yale Divest From War” pin cuts through the noise of neutrality; a Federalist Party sticker signals personal affiliation to conservatism. At Yale, you can learn more about a person’s political stances and moral beliefs through the stickers they stucco to their laptop than in a 15 minute exchange of pleasantries.

But for most of history — and ever present in marginalized communities today — individuals harnessed clothing to signal their loyalties to movements and resistances, embodying and personifying the very message they stand for.

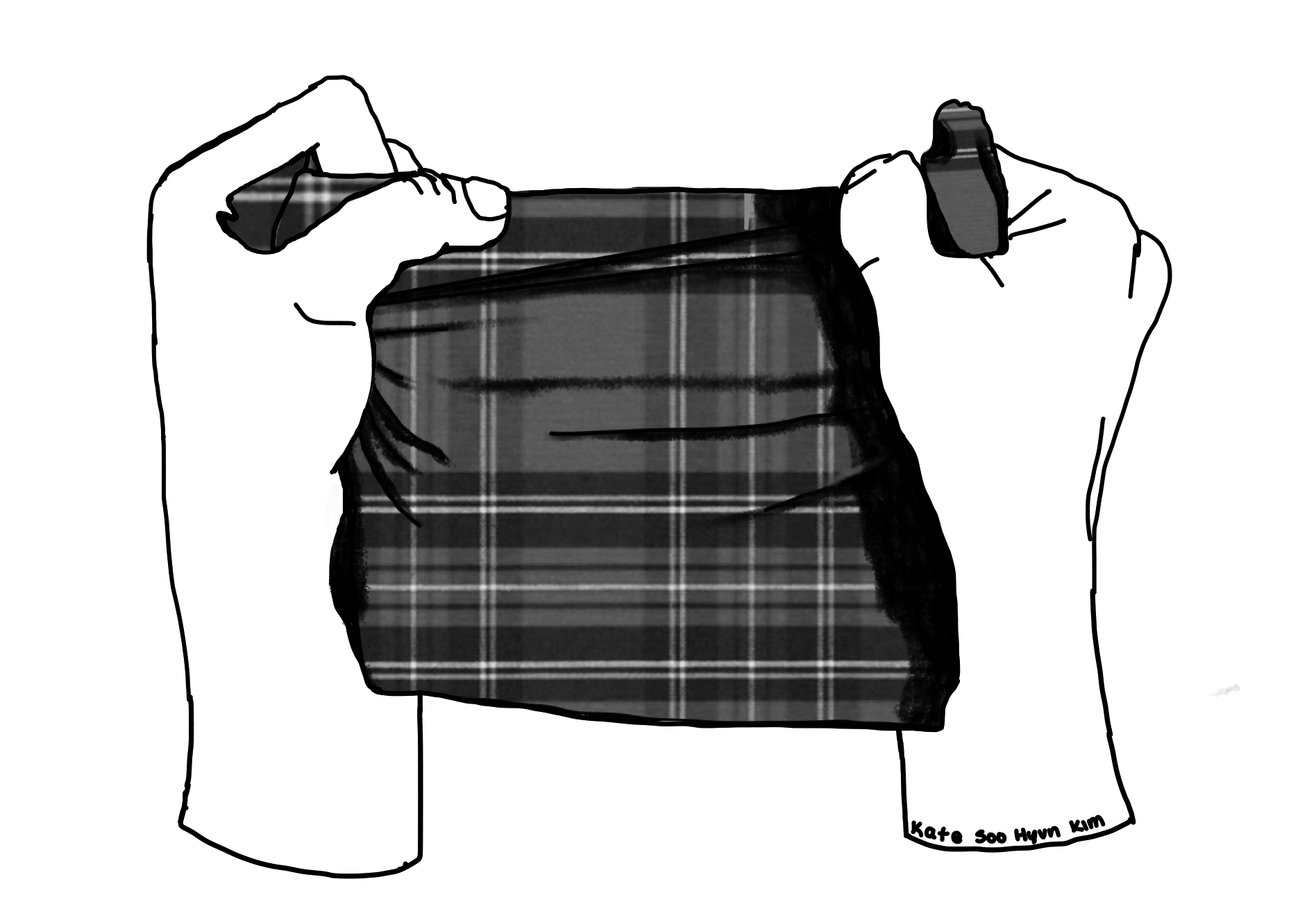

For many movements, symbolic and representative clothing is birthed from a pre-existing item or pattern imbued with cultural, national or religious heritage. Vivienne Westwood’s use of tartan –– or plaid as we Americans call it –– a checkered pattern often using reds, blues and greens, goes back to the pattern’s historic Scottish roots and history as a symbol of subversion.

Since at least the third century A.D., Highlanders — Northern Scottish clan societies — wore wool tartan clothing for its practicality in weathering the rainy Northern European weather. After the Jacobites — rebels who attempted to unseat the Protestant King George II and restore the Catholic house of Stuart — began wearing tartan, the checkered print became synonymous with rebellion. The connotation intensified with the prohibition of clothing items that were often made of tartan in the mid-18th century. However, it wouldn’t be until Queen Victoria’s purchase of Balmoral Castle in Scotland — which she decorated floor-to-ceiling in tartan (very kitschy to say the least) — where tartan’s identity as a subversive pattern became cemented. The queen had, in effect, flattened Scotland’s rich cultural identity into a decorative motif, transforming tartan from a symbol of defiant Highland resistance into a palatable aesthetic for royal consumption — an ironic betrayal of its rebellious roots at the hands of the very monarchy it once opposed. The Highlands, cleared of birthright inhabitants, was conquered as a tourist attraction.

Vivienne Westwood’s use of tartan — both in her own designs and in styling the Sex Pistols — channeled the pattern’s rebellious roots into a direct challenge of the establishment. Drawing on tartan’s history and the Sex Pistols’ role in the punk movement, she cultivated a tangible expression of 1970s punk ideology — wearable anarchy that screamed defiance at the establishment.

In the fashion world today, tartan’s symbolic rebellion lives on in 21st century America as a central pattern of the Emo and Scene communities. Yet much of the original anti-establishment spirit has faded, replaced by school-uniform-inspired trends circulating through both high fashion and fast fashion. School-girl chic — a trend that has crept its way into fashion’s ever-rotating cycle of ins and outs — is a key player in tartan’s rebranding. I’m looking at you, Ralph Lauren… and your so-called “plaid” skirt.

The rebranding of tartan as a sanitized aesthetic of private schools is almost humorously ironic — almost. What was once the uniform of rebellion, banned by the crown for its ties to Jacobite uprisings, was later paraded through Balmoral as decor, its defiant spirit stripped away. Tartan became not a mark of defiance but a stripped-down, drop-shipped token for aristocratic leisure.This transformation isn’t just a quirk of history, it’s a case study in how power erases and repurposes cultural heritage for its own ends.

It begs the question: are you making a fashion statement, or are you wearing the corpse of culture?